Straddling the river of Aurach in the German state of Bavaria lies the small town of Herzogenaurach. It was here in the late 1940s, the Dassler brothers, Adolf and Rudolf, decided to go their own separate ways after a bitter family quarrel. They each started a shoe business, and each company went on to become a giant in the world of sporting goods. But the family feud that started it all soon split on to the streets dividing the town into two distinct faction. This is the story of Puma and Adidas.

Rudolf Dassler, the elder of the Dassler brothers, was born in 1898 and Adolf, who was known to his friends as “Adi”, was born in 1900. Their father worked in a shoe factory, and one might assume that his occupation served as the inspiration for the brothers' foray into the shoe business. In reality, Adi’s father wanted his younger son to become a baker, while Rudolf aspired to become a policeman.

The Dassler brothers before the fallout. Rudolf (left) and Adi (right). At the center is track and field athlete Josef Waitzer who helped the brothers make Dassler shoes in the beginning. Photo credit: Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation

But Adi had his own dreams. He wanted to become an athlete. While pursuing the many sporting disciplines, Adi realized that the athletes of each discipline lacked specialized shoes. Adi believed that if athlete wore shoes optimized for their specific sport, it would certainly result in improved performance. However, before he could chase his ambitions, Adi was drafted into the military for World War 1 and got sent to Europe.

When he returned, Adi set up a small shoe making business in his mother’s wash room, and with the help of experienced shoe maker Karl Zech, he began developing athletic footwear and sandals. After the first World War, Germany was mired in an economic depression and Adi had a hard time procuring raw materials for his shoes. He began scavenging army debris in the war-torn countryside—Army helmets and bread pouches supplied leather for soles, while parachutes supplied silk for slippers. With electrical power insufficient, Adi rigged a leather milling machine to a bicycle mounted on wooden beams, and worked the pedals to power the machine.

Two years later, Adi’s elder brother Rudolf joined him in the shoe making endeavor, and together they established a company named Gebrüder Dassler Schuhfabrik. Adi with his inventive mind, led the technical development, while Rudolf was head of sales and marketing. By 1925 the Dasslers were making leather football boots with nailed studs and track shoes with hand-forged spikes. The company had a dozen workers, and together they produced 50 pair of shoes per day.

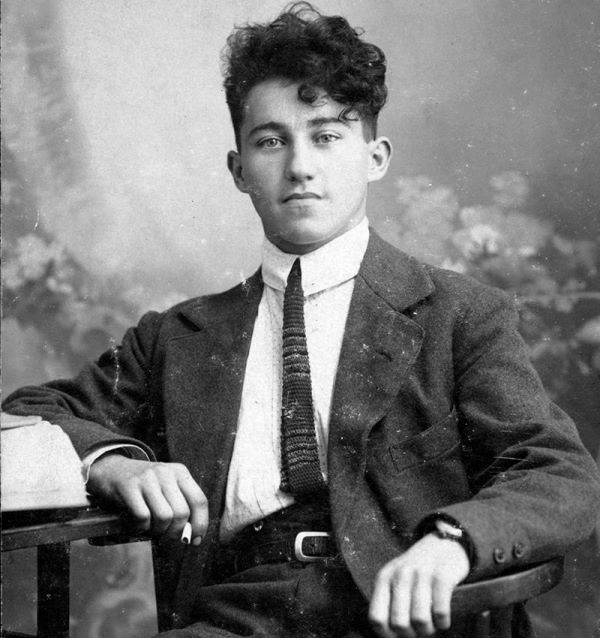

Adi Dassler as a young man.

Rudolf Dassler.

The Dassler brothers shoe business had the first breakthrough in the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam, when German distance runner Lina Radke won the 800 meter gold while wearing a pair of studded Dassler shoes. She also created a new world record as she did so, proving Adi’s theory that it was possible to achieve higher, faster, and further with shoes they designed. Dassler shoes became favorites during the 1932 Olympic Games in Los Angeles, and in the 1936 Berlin Olympics, American track-and-field star Jesse Owens sprinted to four gold medals wearing Dassler shoes. Dasslers' association with Owens proved crucial to the success of the firm. It immediately catapult the company into an international player in the sportswear field, spiking sales overall.

When World War 2 came, Rudolf went back to war while Adi stayed behind to keep the company running. Despite the lack of raw materials, especially leather, due to the war, the Gebrüder Dassler Schuhfabrik kept churning out shoes. In 1943, they were the only company in Germany still producing athletic footwear. The last two years of the war, however, the factory was shuttered and was forced to produce weapons for Germany.

The Dassler shoe factory near Herzogenaurach train station in 1928. Photo credit: Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation

Adi Dassler’s bicycle pedal-powered milling machine. Photo credit: Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation

After the war ended, a rift began to form between the two brothers, exacerbated by the fact that both brothers, their wives and respective children all lived together under the same roof. According to one story, during an Allied bomb attack in 1943, Adi and his wife climbed into a bomb shelter that Rudolf and his family were already in. Adi reportedly remarked: “The dirty bastards are back again,” referring to the Allied war planes, but Rudolf was convinced his brother meant him and his family.

Breaking apart Gebrüder Dassler Schuhfabrik was the only way forward. Adi kept the manufacturing department and went on to form Adidas. Rudolf took the business side of the operation across the river, where he set up a company called Ruda, which eventually became Puma. And with the family, the town itself split into two. Employees took sides. Some joined Adidas and some joined Puma. Each claimed their side of the river and it was not advisable if you were an Adidas fan, for instance, to cross over to Puma’s side wearing Adidas shoes. Each side had its own bakery, its own bars, its own sports clubs.

Helmut Fischer, who worked for Puma for four decades, has his employer’s logo tattooed onto his calves and on his back. And when he meets someone for the first time, he says he “automatically” looks at what they’re wearing on their feet before saying hello.

The habit is so widespread in Herzogenaurach that it has been nicknamed “the town of bent necks”.

The adidas shoe factory in the 1950s. Photo credit: Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation

Adidas chief executive Herber Hainer says that when he started working for the company close to forty years ago, they were forbidden from even mentioning the name Puma. They always had to speak of ‘the competitor on the other side of the Aurach”.

But not everyone was willing to be caught up in the family feud. Klaus Roemmelt, who owns a 100-year-old bakery on Herzogenaurach, told reporters: “My parents always had a pair of shoes of each brand in their car, which they would put on,” depending on which firm they were delivering to.

Others took advantage of the rivalry. When a handyman had to visit Rudolf’s house for work, they would sometimes wear Adidas shoes on purpose. When Rudolf would see their footwear, he'd tell them to go to the basement and pick out a pair of Puma shoes, which they could have for free.

The brothers took the feud to their grave. Even in death, they refused to lie next to each other. Both brothers, while buried in the same cemetery, their graves are about as far apart as possible.

But things are changing. Frank Dassler, the grandson of Rudolf Dassler, who grew up wearing Puma shoes, now works for Adidas as the company’s head legal counsel. Of course his decision to join the rival company was not taken too kindly by his family. It also raised more than a few eyebrows in the town. But Frank doesn’t care.

“This rivalry was years ago, it's history now,” he said.

In 1987, Adolf Dassler's son Horst Dassler sold Adidas to French industrialist Bernard Tapie, while Rudolf's sons Armin and Gerd Dassler sold their 72 percent stake in Puma to Swiss business Cosa Liebermann SA. Since the companies went public they are no longer in family ownership. The workforce has also diversified. Now most workers aren’t from town and the friction between them have eased into a less aggressive rivalry. Even today, employees of the two companies will tease each other about their clothes when they meet on the street, but nowadays it's more to poke fun.

Puma branding on a manhole cover in Herzogenaurach. Photo credit: ramanzel/Flickr

The town of Herzogenaurach. Photo credit: Stefan Müller/Flickr

References:

# Chronicle And Biography Of Adi & Käthe Dassler, Adi & Käthe Dassler Memorial Foundation

# Herzogenaurach, a German town divided by Adidas-Puma brotherly rivalry, Hindustan Times

# The Town that Sibling Rivalry Built, and Divided, DW.com

Comments

Post a Comment