In The Knave of Harts, a collection of satirical poems penned by Samuel Rowlands, the English poet makes an allusion to a certain German called Peter Stumpp who was executed for being a werewolf.

A German (called Peter Stumpe) by charme

Of an inchanted Girdle, did much harme,

Transform'd himselfe into a Wolfeish shape,

And in a wood did many yeeres escape

The hand of Iustice, till the Hang-man met him,

And from a Wolfe, did with an halter fet him:

Thus counterfaiting shapes haue had ill lucke,

Witnesse Acteon when he plaid the Bucke.

In the year this literary work was published, 1612, Peter Stumpp’s story was widely known throughout Europe. However, as the centuries passed, this tale gradually faded into obscurity, and any written accounts about this unfortunate man became lost to the annals of history.

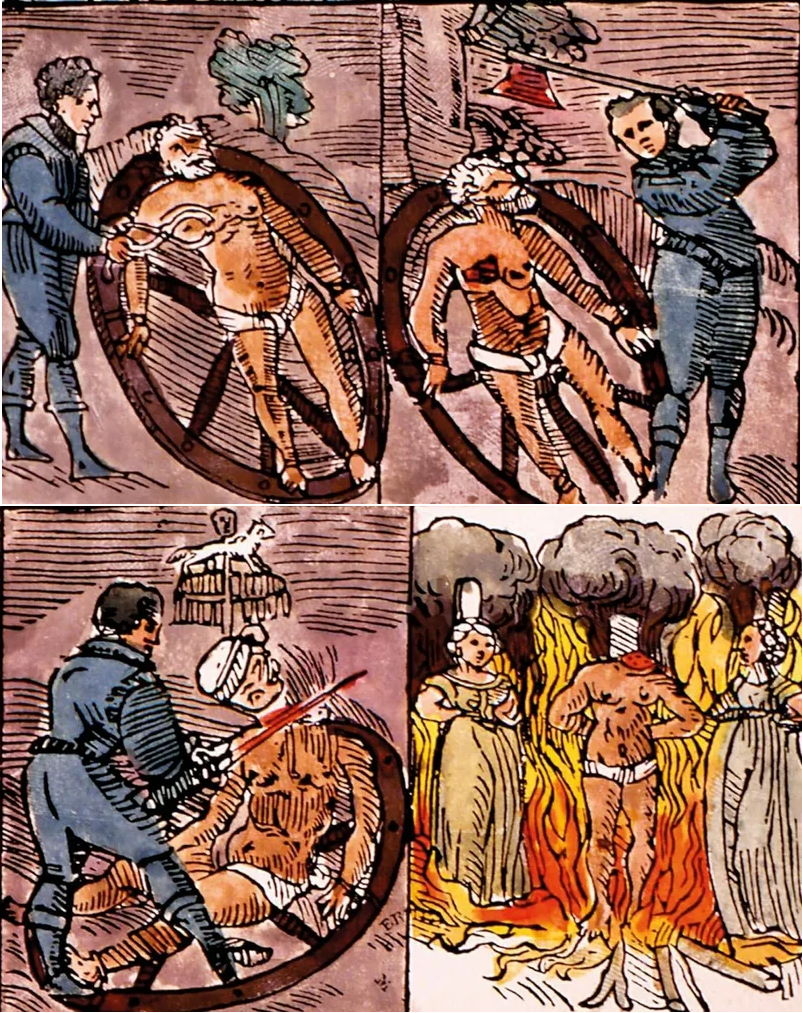

Composite woodcut print by Lukas Mayer of the execution of Peter Stumpp.

In 1920, an English clergyman and author named Montague Summers espied a long forgotten pamphlet in the British Museum detailing the singular case of Peter Stumpp. The pamphlet goes into detail on Stumpp's life, including his crimes and the trial that ensued after his capture. Almost everything we know about this event comes from these 16 pages. The original broadsheet was published in German, from which an English translation was made, of which only two copies now exist. Aside from the one in the British Museum, there is another one in the Lambeth Library, also in London. No copy of the original German pamphlet survive.

Who was Peter Stumpp?

Peter Stumpp was a wealthy farmer in the rural community of Bedburg, located in the electorate of Cologne, Germany. It is possible that Peter Stumpp was not his real name, but a nickname earned because he lost his left hand in an accident. Another alias that is associated with his name is Abal Griswold.

Peter Stumpp was born in the mid-1500s, possibly around 1564, in the village of Epprath, near Bedburg. He had two children—a girl called Beele (Sybil), who was around 15 years old, and a son of an unknown age. He was a widower.

Stumpp was known for his amiable character, as described in the 1590 English pamphlet:

He would go through the streets of Cologne, Bedburg, and Epprath, in comely habit, and very civilly, as one well known to all the inhabitants thereabout, and oftentimes was he saluted of those whose friends and children he had butchered, though nothing suspected for the same.

Werewolves attack

Starting from the mid-1560s, an increasing number cattle around Bedburg began turning up dead with their abdomens ripped open and mutilated. The villagers naturally suspected wolves. But when women and children of the town also began to fall victim to these attacks, the townsfolk became convinced something more sinister was at play.

People became afraid to venture out of their houses, and whenever they did, they did only in large armed groups. Sometimes when travelling from one town to another, they would find dismembered limbs of victims strewn in the fields. These sights sent panic through the populace. When a child would go missing, the parents would immediately assume all was lost and that the wolf had taken another victim.

The attacks continued for 25 years, during which time countless number of men, women, children, cattle and sheep were devoured by the vile creature.

In 1589, there was an extraordinary incident. Some children were playing in a meadow, when suddenly out of the woods emerged a wolf, who caught a young girl by the collar of her coat, but the collar was so stiff and well made that the wolf was unable to pierce through it. An outcry was raised and the wolf let go his hold and ran away. The men gave chase and soon had the animal cornered, but as they moved in for the kill, they found that the wolf had disappeared and in its place was Peter Stumpp. It’s unclear whether the men actually saw the wolf transform or Stumpp just happened to be at the wrong place at the wrong time.

Capture and Execution

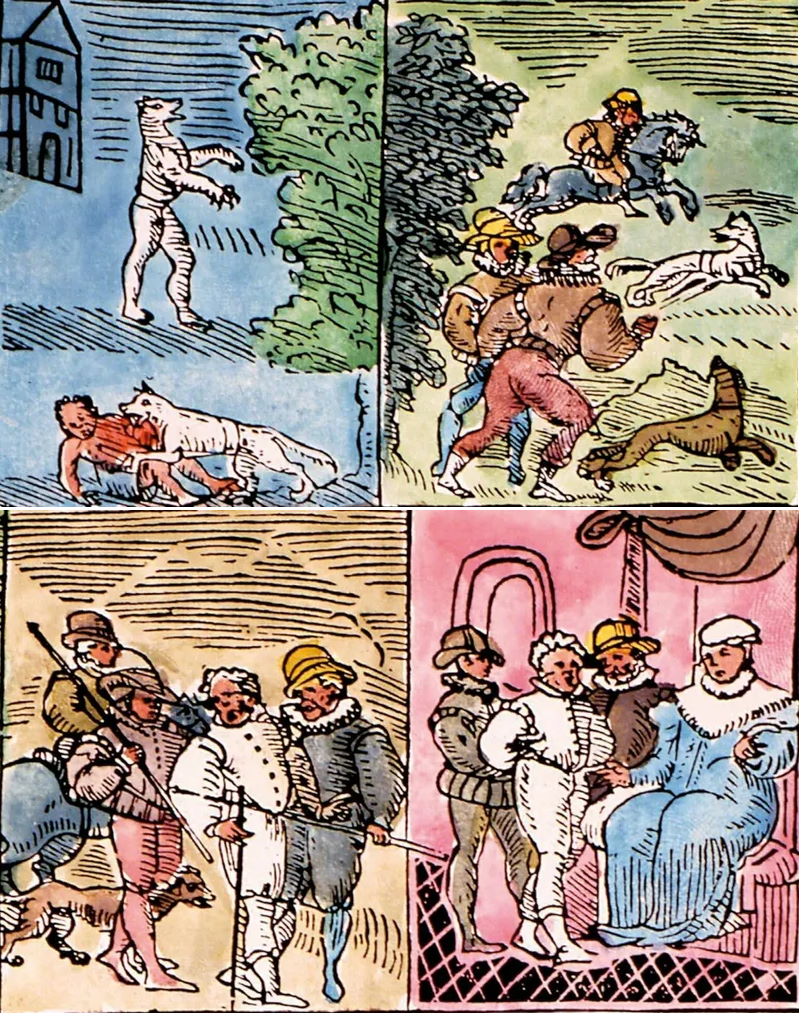

Illustrations that accompanied the English pamphlet. In this colorized version we can see the episodes from his story showing Stump as a werewolf, his arrest by authorities, his interrogation, and the stages of his brutal execution. Photo credit: National Geographic

Either way, Stumpp was captured and tortured on the rack, eventually resulting in his confession to a number of horrific crimes. Stumpp claimed that he had been practicing black magic since he was 12 years old. He confessed to having made a pact with the devil, who in return had given him a magic girdle that allowed him to transform into “the likeness of a greedy, devouring wolf, strong and mighty, with eyes great and large, which in the night sparkled like fire, a mouth great and wide, with most sharp and cruel teeth, a huge body, and mighty paws.” Removing the belt would change him back to his human form. Stumpp claimed he had tossed the belt into a certain valley. The magistrate sent for it to be retrieved but no such belt was ever found.

Stumpp confessed to killing and eating fourteen children and two pregnant women, whose fetuses he ripped from their wombs and “ate their hearts panting hot and raw.” Stumpp even confessed to killing his own son, whose brain he was reported to have devoured.

Stumpp was also accused of and later confessed to having an incestuous relationship with his daughter. His son is thought to be the result of this relation. In addition to this, he confessed to having had intercourse with a succubus sent to him by the Devil.

Related:

The Wolf of Ansbach

How The Beast Of Gévaudan Terrorized 18th-Century France

For his alleged crimes, Stumpp was put to death in the most gruesome way possible: his body was laid on a wheel, and with red hot burning pincers, the flesh from the body was pulled off from the bones at several places; after that, his legs and arms were broken with an wooden axe. His body was decapitated and then burned in a pyre. His unfortunate daughter and his mistress, Katherine Trompin, were also put to the stake as accessories to the murders. As a warning against similar behavior, local authorities erected a pole with the torture wheel and the figure of a wolf on it, and at the very top they placed Peter Stumpp's severed head.

It's unclear why Stumpp became the prime suspect for the villagers. Some historians believe it’s possible that Stump was a murderer. His scandalous relationship with his daughter as well as his mistress, who was a distant relative, likely tarnished his reputation throughout Bedburg and could have added fuel to the accusations of Stumpp being the werewolf. It is also possible that Stumpp was made a scapegoat. The events took place during a period known as the Cologne War (1583-88), a conflict between the Protestants and the Catholics. Stumpp was a known Catholic who had converted to Protestantism. The Catholic faction which had secured control of the Bedburg region might have thought to make an example out of Stumpp to dissuade any Protestants from thoughts of rebellion.

The execution of Peter Stumpp was not an isolated incident in the history of werewolf trials. Such trials were prevalent in Europe from the early 15th to the 18th century, reaching their zenith in the 17th century. The persecution of alleged werewolves, coupled with the associated folklore, became intertwined with the broader phenomenon of witch-hunts that swept across Europe during this period. However, it's important to note that accusations of lycanthropy, or the transformation into a wolf, constituted only a small fraction of witchcraft trials.

The 1589 case of Peter Stumpp marked a notable surge in both the interest in and persecution of supposed werewolves, particularly in French-speaking and German-speaking regions of Europe. Werewolf trials eventually extended to Livonia in the 17th century, becoming the predominant form of witch-trial in that area. This phenomenon endured longest in Bavaria and Austria before gradually fading away in the early 18th century in Carinthia and Styria.

Comments

Post a Comment