The city of Dundee on the Firth of Tay, on the east coast of Scotland, was a major whaling port in the 19th century. But few locals had actually seen a whale. That changed in late 1883 when a humpback whale began to frequent the coast, often swimming up and down the River Tay in search of food. The attraction to the river was the young herrings with which the firth was abound at that time. For several weeks, starting from early November, the humpback was seen in this vicinity entertaining inhabitants with its “gymnastic performances” and enticing whalers whose fleet was laid up in the harbor for the winter. After a few days, the whalers decided to catch this potential profit that had presented itself on their doorstep.

A postcard of the Tay Whale. Photo: David McGreevy/Flickr

For six weeks, the whalers tried in vain to conquer the beast that had earned the nickname “Monster”. Several times the whalers gave chase, but each time the humpback managed to escape. The local newspaper, the Dundee Courier, gave a blow-by-blow account of these attempts—”This monster still continues to keep several members of our whaling fleet on the alert,” wrote the newspaper on 12 December 1883.

Finally, on 31 December 1883, the quarry was struck by several harpoons. The mighty beast, though injured and heavily bleeding, showed great strength and endurance by towing two six-oared rowing boats and two steamboats up and down the estuary. A great excitement ensued when news broke out of the successful harpooning and a large number of people began to line up the coast and the estuary in order to view the ensuring battle. Others piled up on whatever boat was available and began following the chase. By evening the whale had headed out to open sea, dragging along the attached flotilla—its captors firmly holding on to the lines with hopes of landing the monster. After an all-night struggle, the lines were reluctantly parted, and the whalers returned home tired and empty handed, but convinced that “mortal injury had been done.”

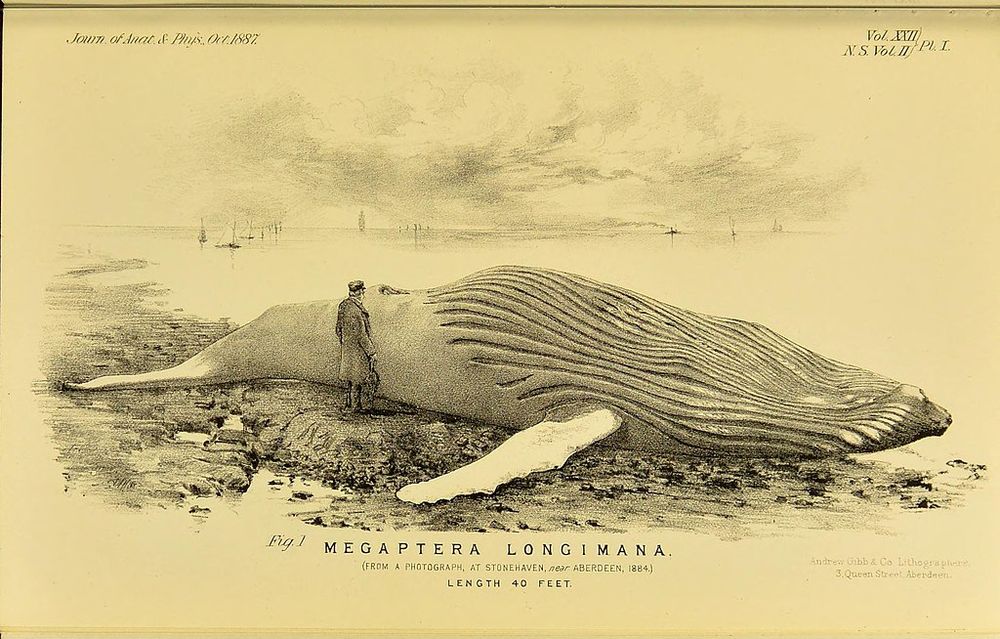

A week later, the whale’s carcass was found floating 6 miles off the shore. Some fishermen from Gourdon towed the whale to Stonehaven and dragged it onto the beach. John Struthers, an anatomist at the University of Aberdeen, who never missed an opportunity to dissect whales, quickly arrived at the site. Struthers measured that the whale was 40 feet in length from the snout to the tail, and about 23 feet in girth at its widest part.

The Tay Whale, from John Struthers’s “Memoir on the Anatomy of the Humpback Whale, Megaptera Longimana”.

Struthers wanted to have the whale for himself, but for that to happen, he would have to outbid everyone else at the open auction. An intense competition of bids ensued between Professor Struthers and John Woods, an entrepreneur from Dundee and an oil merchant, better known as "Greasy Johnny". In the end, it was Woods who made the final bid, buying the 16-ton cetacean for £226. However, it was arranged that Struthers would eventually take possession of the whale’s skeleton for anatomical purposes once Woods was done.

Woods had the whale removed to Dundee, where he expected to put the monster on display. Several thousand spectators gathered at the dock at the dead of night to watch its arrival. The massive carcass was hauled to Woods’s scrap yard in a bogie pulled by twenty horses. The effort crushed two heavy-duty lories and almost turned the whale carcass into a “spectacular funeral pyre” when a naptha flare, used to light up the area, was knocked over and set some loose oil on fire. These mishaps delayed progress, and the half-mile journey took 26 hours to complete.

Woods immediately placed the whale carcass on public display and charged visitors a shilling for a view. On the first Sunday alone, 12,000 people came to view the exhibit, and over the next fortnight, some 50,000 people had seen the whale. The exhibit also inspired a poem by William McGonagall, a poet with a regrettable reputation for outrageous compositions. The Famous Tay Whale is no different. Two of the versus run:

And my opinion is that God sent the whale in time of need,

No matter what other people may think or what is their creed;

I know fishermen in general are often very poor,

And God in His goodness sent it drive poverty from their door.So Mr John Wood has bought it for two hundred and twenty-six pound,

And has brought it to Dundee all safe and all sound;

Which measures 40 feet in length from the snout to the tail,

So I advise the people far and near to see it without fail.

By late January, the whale had been dead for nearly four weeks, and even in the cool Scottish winter, the carcass had decomposed to such an extent that there wasn’t anything recognizable left except its tail. The smell itself was beginning to keep visitors away.

The Tay Whale, from John Struthers’s “Memoir on the Anatomy of the Humpback Whale, Megaptera Longimana”.

Realizing that there was no more money left in the spectacle, Woods invited Struthers to perform a dissection on the famous specimen. Struthers, who was no alien to stinking carcasses, arrived with two of his assistants to discover that Woods had made the dissection public and was charging people for a view. Surrounded by a crowd and a band playing in the background, Struthers opened the animal and found the viscera to be completely decomposed and turned into a pulp. When Struthers tried to reach out for the heart, his hands went through. Struthers salvaged parts of the vertebrae, sternum, ribs and hyoid for detailed examination and then at Wood's request,the remains were embalmed, a wooden backbone and frame introduced, and the whale stuffed and stitched back to its original form.

The partially-taxidermied whale then went on a road trip through Edinburgh, Liverpool, London and Manchester, where it was displayed to awestruck audiences, before returning to Dundee in August, seven months after the whale was killed. Struthers was invited back to complete the removal of the skull and the remaining bones.

Struthers eventually wrote seven anatomy articles over the next decade on the whale, and ultimately published a complete monograph on it in 1889, entitled Memoir on the Anatomy of the Humpback Whale, Megaptera Longimana.

The whale's skeleton is now on display at the McManus Galleries in Dundee.

Skeleton of the Tay Whale at the McManus Galleries in Dundee. Photo: VisitScotland/Kenny Lam

References:

# The Tale of a Whale, McGonagall Online

# Williams, M. J. “Professor Struthers and the Tay Whale”, Scottish Medical Journal

# John Struthers, “Memoir on the anatomy of the humpback whale, Megaptera Longimana”, Archive.org

Comments

Post a Comment