The act of boycotting an organization or a person dates back to centuries, but the word “boycott” itself is relatively new. It entered English usage only in 1880 after a highly publicized campaign to ostracize a certain English land agent gained wide coverage in the British press. His name was Charles Cunningham Boycott.

Charles Cunningham Boycott was born a “Boycatt” in 1832, but his family changed the spelling of his surname, for reasons unknown, from Boycatt to Boycott when the lad was nine years old. Henceforth known as Charles Boycott, the young and spirited boy entered the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, in 1848, in hopes of serving in the Corps of Royal Engineers. But after failing a periodic exam, Boycott was discharged from the academy. Seeing the boy’s eagerness to serve in the military, his family bought him a commission in the 39th Foot regiment. Alas, Boycott’s initial enthusiasm to be a soldier waned, and just three years later, he decided to quit and became a landlord.

Photo: Pierre (Rennes)/Flickr

In 1854, Boycott moved to Achill Island, a large island off the coast of County Mayo, and acquired some land there. In 1873, Boycott moved to the mainland and became the land agent to the 3rd Earl of Erne who owned more than 40,000 acres of land in Ireland, spread over different counties. Boycott’s responsibility was to collect rents from tenant farmers and evict those who didn’t or couldn’t pay. Boycott, according to his biographer Joyce Marlow, believed “in the divine right of the masters, and the tendency to behave as he saw fit, without regard to other people's point of view or feelings.” Boycott’s high handedness and unsavory character made him unpopular with the tenants. He was known to exact fines on hapless tenants on the most pettiest of transgressions, such as if their livestock strayed on to his lands, or if they were late to work. These fines sometimes exceeded their wages.

In 1879, Michael Davitt, the son of a small tenant farmer in County Mayo, formed the Irish National Land League, whose aims were to reduce rents and to stop evictions. The league’s ultimate goal was to make tenant farmers owners of the land they farmed. In September 1880, Lord Erne's tenants were due to pay their rents. The tenants requested Lord Ernie a rent reduction of 25 percent because of poor harvest the previous year, but Lord Ernie would allow a concession of only 10 percent. Boycott was then granted permission to recover the outstanding rents, and evict eleven tenants who had refused to pay. Some of the tenants paid their rents in due course, but three families were subsequently evicted for non-payment.

A caricature of Charles Cunningham Boycott that appeared in Vanity Fair magazine, January 29, 1881. Photo: Wikimedia

The eviction of three tenants and their families became a rallying cause for Michael Davitt and his Land League. Outraged by the events, the Land League called a mass meeting to discuss how to rise against the tyranny. A few days previously, Charles Stewart Parnell, Member of Parliament and leader of the Land League, had given a speech in Ennis, County Clare to a crowd of Land League members, in which he spoke:

When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted, you must shun him on the roadside when you meet him – you must shun him in the streets of the town – you must shun him in the shop – you must shun him on the fair green and in the market place, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him alone, by putting him in moral Coventry, by isolating him from the rest of the country, as if he were the leper of old – you must show him your detestation of the crime he committed.

Based on these ideas, the Land League called a general strike and instructed everyone in the community to socially ostracize Boycott and cease all relations with him. Those who didn’t were threatened with “ulterior consequences”. Subsequently, Boycott found himself isolated in his community. No one would buy from him; no one would sell to him. He was unable to harvest his own land or transact business of any kind in the community. Even the postman stopped coming.

Helpless at his predicament, Boycott penned a desperate letter to The Times in mid-October.

“My blacksmith has received a letter threatening him with murder if he does any more work for me, and my laundress has also been ordered to give up my washing. ... The shopkeepers have been warned to stop all supplies to my house, and I have just received a message from the post mistress to say that the telegraph messenger was stopped and threatened on the road when bringing out a message to me,” he explained. “My crops are trampled upon, carried away in quantities, and destroyed wholesale. The locks on my gates are smashed, the gates thrown open, the walls thrown down, and the stock driven out on the roads”.

Most pressing of these matters were his crops which Boycott feared would rot if help couldn’t be found to harvest them. Upon learning Boycott’s situation, a few sympathizers in Belfast and Dublin raised funds and organized a relief expedition consisting of about fifty men and labourers who arrived in Mayo County to harvest the crops. In addition, some nine hundred soldiers were sent to protect the labourers anticipating violence from the locals. The entire regiment stayed in town for two weeks. They erected tents on Boycott’s land, cut his trees for firewood, ate his livestock, and left his well-kept property in a trampled mess. Worse still, some £10,000 were spent to rescue crops worth at most £350.

The Boycott affair became a big news in Ireland, England and other English-speaking countries. Boycotting dramatically strengthened the power of the peasants, and by the end of 1880, there were reports of boycotting from all over Ireland. The events at Lough Mask also increased the power of the Land League, and the popularity of Parnell as a leader.

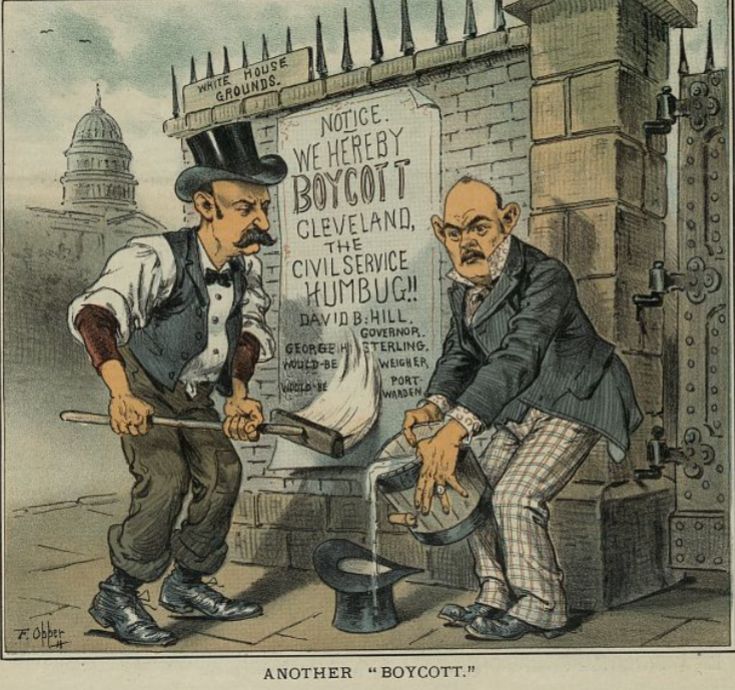

One of many illustrations humorizing the growing phenomenon of “boycott” that appeared in newspapers and magazines in the late 19th century. Photo: Library of Congress

It is difficult to say exactly when the word “boycott” entered English usage. According to journalist James Redpath, the term was coined by local priest Father O'Malley. Redpath recalled a conversation he had with O'Malley, where Redpath said: “When the people ostracise a land-grabber we call it social excommunication, but we ought to have an entirely different word to signify ostracism applied to a landlord or land-agent like Boycott. Ostracism won't do – the peasantry would not know the meaning of the word.” Father O'Malley agreed. He looked down, tapped his big forehead, and said: “How would it do to call it to boycott him?”

Soon, the new word was everywhere. The Illustrated London News described how “to Boycott” had already become a verb active, signifying to 'ratten', to intimidate, to 'send to Coventry', and to 'taboo'. Apparently, no other word in the English language existed that adequately described the dispute. In 1888, the word was first included in A New English Dictionary Based on Historical Principles, later known as the Oxford English Dictionary. The word boycott eventually passed into foreign languages which also lacked comparable words for it. A labor union in Topeka, Kansas, even launched a weekly paper called The Boycotter in 1885 to advocate for workers’ rights.

Meanwhile Charles Boycott, having wrecked his already tattered repute, quietly left Ireland and became a land agent for Hugh Adair's Flixton estate in Suffolk, England. Once, when Boycott and his family went to the United States to visit some friends, he registered his name as ‘Charles Cunningham’ to avoid drawing attention. But New York newspapers got wind of his arrival. The New York Tribune said that, “The arrival of Captain Boycott, who has involuntarily added a new word to the language, is an event of something like international interest.”

After some months, Boycott returned to England and became a land agent for Hugh Adair's Flixton estate in Suffolk. He died at his home in 1897, but his name lives on in infamy forever.

Comments

Post a Comment