In the early 19th century, a deplorable trade developed in New Zealand between the indigenous Maori people and the European merchants. The westerners supplied the islanders with firearms, and in return the Maoris provided the English merchants with decapitated and dried heads of deceased Maoris, featuring beautiful patterns tattooed on the skin. These heads are known as mokomokai, and they are a valuable Maori artifact.

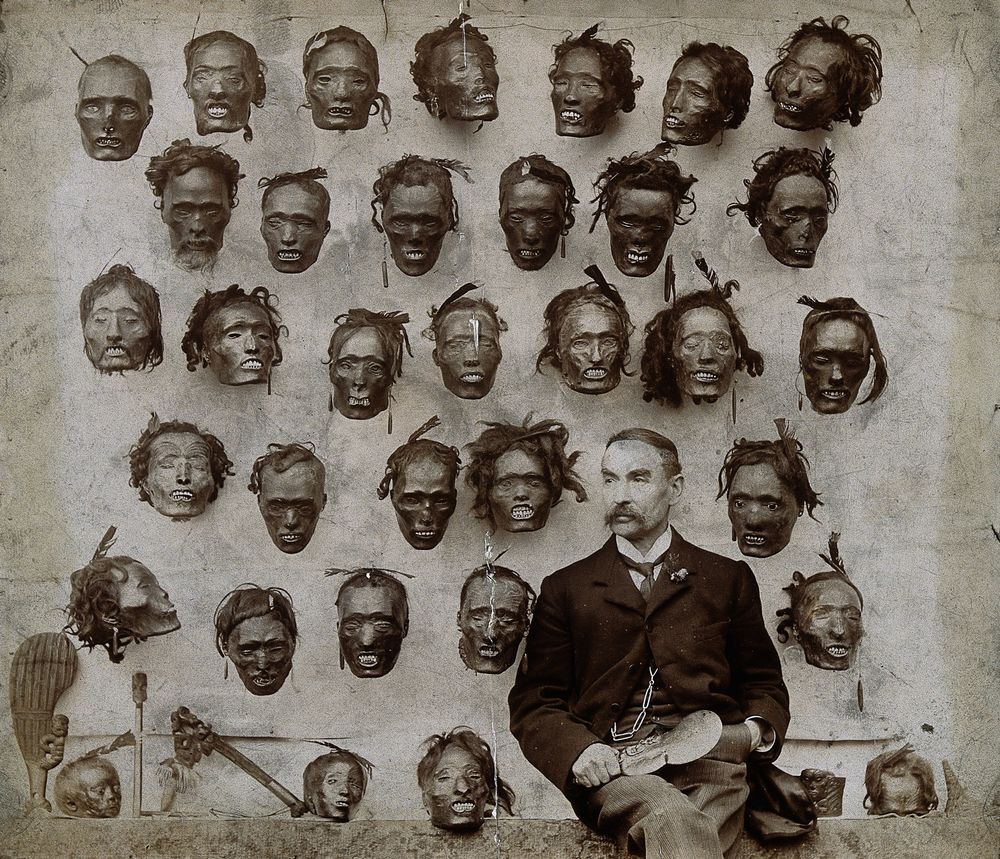

Mokomokai collection of British army officer Horatio Gordon Robley. Photo: Wikimedia

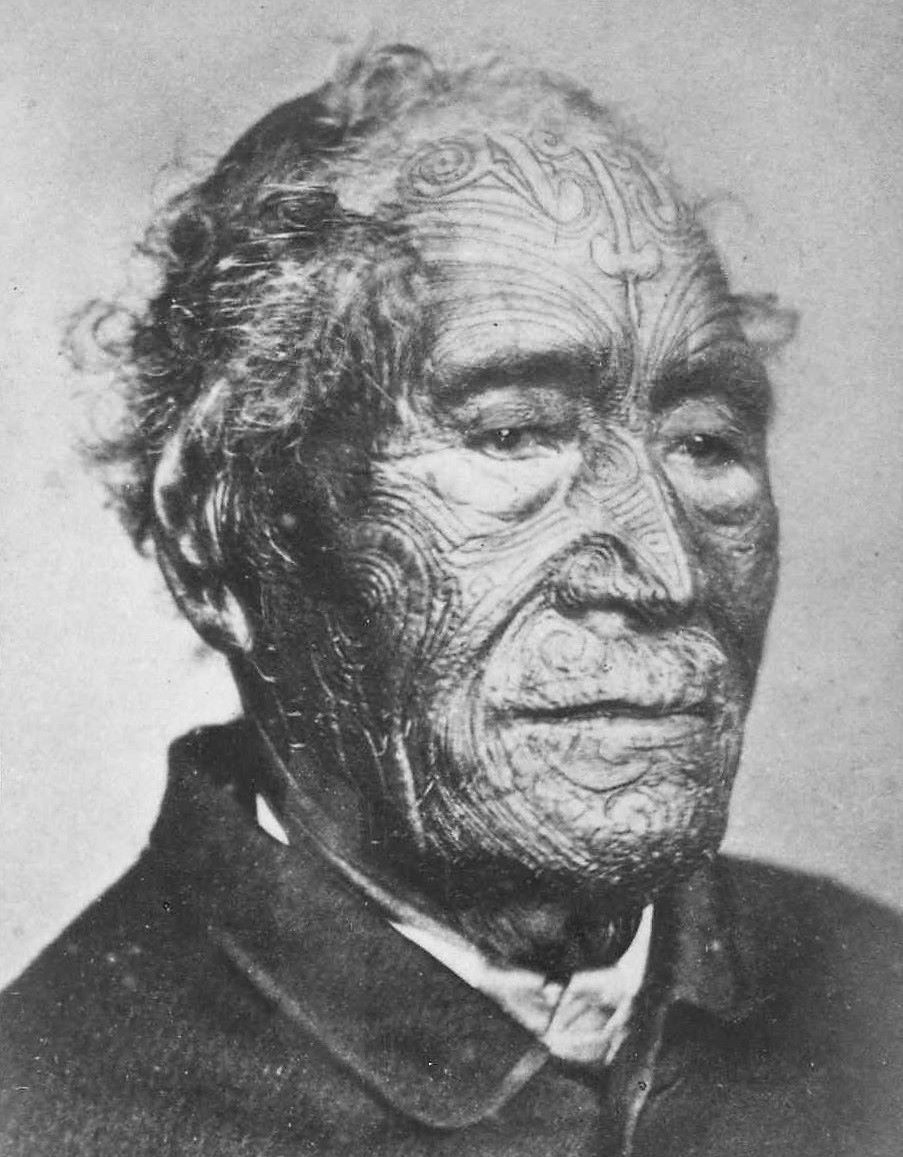

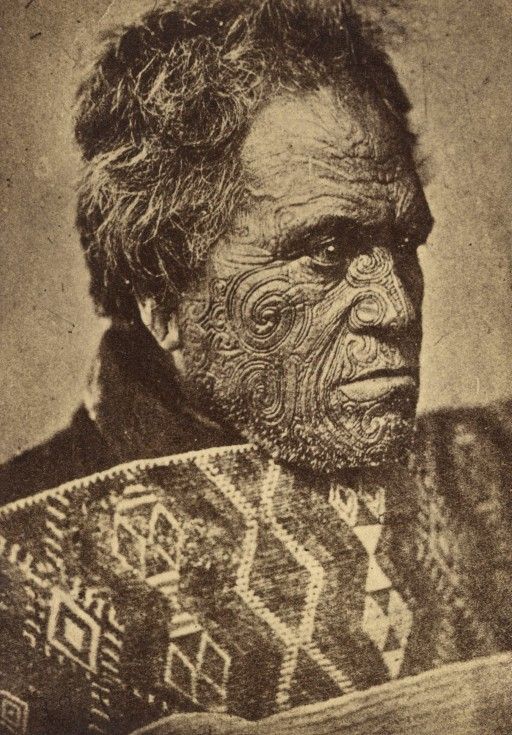

Facial tattoos, known as moko, were once very common among the Maori people. Unlike modern tattoos, they were much more than mere body decorations. Tattoos were intricately connected to the social, political, and religious life of the Maori. They denoted high status and rank, and their design often contained information about a person’s lineage, tribe, occupation, rank, and exploits. Receiving moko constituted an important milestone in one’s life and often marked rites of passage such as puberty.

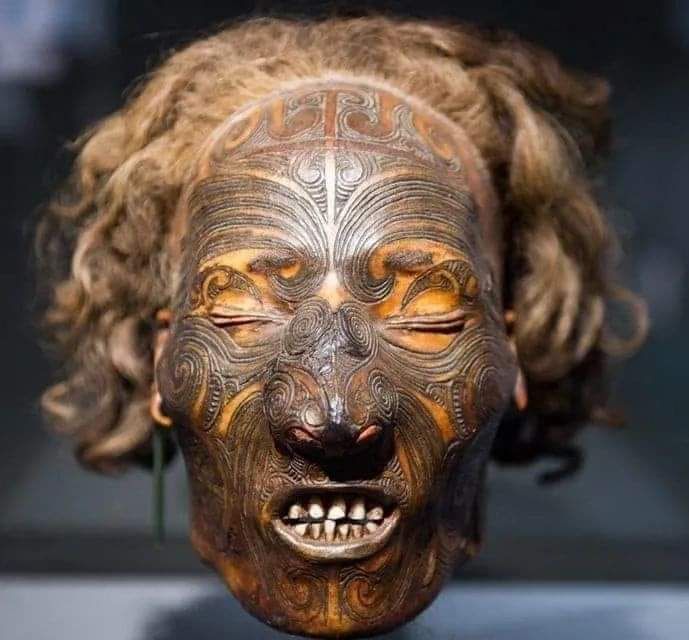

When someone with moko died, often the head was preserved. First the brain and eyes were removed, and the orifices sealed with flax fibre and gum. The head was then boiled or steamed in an over, before being smoked in open fire and dried in the sun for several days. It was then treated with shark oil. The preserved heads, or mokomokai, became cherished treasures of the family and only brought out for special occasions.

The Maori also took heads of enemy chiefs killed in battles as trophies of war, and turned them into mokomokai. These heads played an important role in rituals and ceremonies relating to war and peace. They were important in diplomatic negotiations between warring tribes, with the return and exchange of mokomokai being an essential precondition for peace.

Facial tattoo of Maori chief Tuterei Karewa. Photo: Wikimedia

Moko tattoos on the face of Maori chief Tāmati Wāka Nene. Photo: Wikimedia

Moko tattoos on the face of Maori chief Tomika Te Mutu. Photo: Wikimedia

In 1770, when HMB Endeavour captained by James Cook was in New Zealand, his botanist Joseph Banks came upon an elderly Maori on a canoe with three heads on board. Banks pressured the old man to part with his heads but the man hesitated, at which Banks threatened to cancel the barter for which the old man had come unless he was willing to sell his heads. Left with no choice, the Maori man was forced to sell the head of a 14-year old teenager in exchange for a pair of underwear. This was the first time a mokomokai came under the possession of a European, and no doubt the severed head must have aroused great interest when it was brought back to England. Over the years, more mokomokai were traded from the Maoris and these tattooed heads were sold as curios, artworks and as museum specimens which fetched high prices in Europe and America.

One of the most prized item for barter became the musket. War has always been a part of traditional Maori life, but the introduction of guns changed the nature of war. Tribes who obtained guns gained an enormous advantage over their neighbors, and this forced other tribes in the region to procure guns to defend themselves, and they went to any means to obtain them.

Initially, the Maori traded flax, potatoes, slave women, and tattooed heads for guns and ammunition. But as the demand for tattooed heads increased, other trade items were deemed less valuable. For example, it took two tons of flax to purchase one musket. But the same could be obtained by trading only two heads.

A mokomokai head that was returned to New Zealand.

As the Maori got caught up in the arms race, they became desperate. They tattooed their slaves and prisoners before beheading them and selling these heads. Sometimes people were tattooed after deaths.

The guns that got introduced into New Zealand in exchange of tattooed heads had devastating effects, with bloody intertribal Musket Wars that led to the deaths of between 20,000 and 40,000 people and the enslavement of tens of thousands of Maori.

In 1831 the Governor of New South Wales issued a proclamation banning further trade in heads out of New Zealand, and during the 1830s the demand for firearms diminished because every surviving group was fully armed. In 1840 the Treaty of Waitangi was signed, and New Zealand became a British colony. By then, the export trade in mokomokai had virtually ended. The Maori also stopped preserving the heads of friends and relatives out of respect, and also because of fear that these heads would get stolen because of the general demand in mokomokai. The practice of Moko itself began to decline. As Rev. G. Woods explains: “In the first place, no man who was well tattooed was safe for an hour unless he was a great chief, for he might be at any time watched until he was off his guard and then knocked down and killed, and his head sold to the traders”

Despite the ban in the trade, tattooed heads continued to be sold for several years after. It is estimated that hundreds of these heads were bought and sold in Europe and America during the peak years of the trade in mokomokai from 1820 to 1831. Some have been repatriated to New Zealand, but many remain in museums and private collections.

References:

# Palmer and Tano, “Mokomokai: Commercialization and Desacralization”, Research Gate

# “The trade in preserved Maori heads”, Stuff.co.nz

Comments

Post a Comment