In the early 19th century, arsenic was most widely used to kill rats and insufferable husbands alike. The chemical element was odorless and had a mild taste which allowed a scheming wife to mix it with a wide variety of flavored foods and feed the unsuspecting victim. A medical examiner usually couldn’t tell whether the poison was involved, because the symptoms—diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain—were similar to those of cholera, which was common at the time. Chemical tests to detect the presence of arsenic existed, but these were time consuming and the results were often inconclusive.

Marie Lafarge, lithograph by Gabriel Decker.

In 1836, a Scottish chemist named James Marsh presented to the Royal Society of Arts of London the first reliable method to separate minute quantities of arsenic. The ‘Marsh test’ soon became the decisive tool in all poisoning cases, eliminating the need for discussion at a trial. The most successful use of the Marsh test at a courtroom happened in Tulle, France in 1840 with the celebrated LaFarge poisoning case.

Marie Lafarge was the 23-year-old wife of a brutish ironworker named Charles Lafarge. Before marriage, Charles had presented himself as a wealthy businessman and the owner of a château, but it turned out that he was actually bankrupt and had married Marie because of her dowry which allowed him to pay off some of his debt. Marie had found Charles to be repulsive, but had agreed to the marriage because of his presumed wealth. Now with that illusion broken, Marie found herself trapped in a marriage with a man she didn’t love and with in-laws who were less than welcoming. Even her new home in Le Glandier was in a state of disrepair and full of rats.

Enraged at being deceived, Marie locked herself up in the bedroom on the first night at the estate and composed a letter to Charles begging him to release her from the marriage, while threatening to take her life with arsenic. Later, Marie was cajoled by her mother-in-law into giving the marriage a chance. Charles too agreed to make concessions and promised not to assert his “marital privileges” until he had restored the estate to its original condition.

Also read: The Angel Makers of Nagyrév

Over the next few weeks, the couple’s relationship seemed to improve. Charles kept his word and arranged to have the mansion renovated. He provided his young bride with subscriptions to magazines and newspapers, and membership in the local lending library, so that she could pursue her intellectual interests. He also bought Marie, at great cost, a piano and an Arabian horse for her to ride. During this time, Marie wrote letters to her school friends telling them how happy she was. She also tried to help her husband in his business by writing letters of recommendation for him, which he could use to secure loans.

Less than a year after marriage, Charles went to Paris to raise money for his ironworks. As it was Christmas, Marie sent her husband a cake in the spirit of the season, which Charles ate and immediately fell violently ill. Charles threw the cake away believing it had become contaminated during transit, and returned to Le Glandier, still feeling ill. Marie devoted herself to her husband's care, providing him with food and drink, and attempting to make him comfortable. As Charles’s condition deteriorated, the family appointed a young woman named Anna Brun to look after Charles.

Anna noticed that Marie used to mix a white powder into the eggnog before serving it to Charles. On questioning, Marie replied that the powder was “orange-blossom sugar”, but Anna was suspicious. She took an unfinished glass of eggnog to the physician and showed him the white flakes floating on the surface. But the doctor dismissed it saying it might be flakes of plaster that had fallen from the ceiling. Anna was not convinced. Another day, she saw Marie stir more white powder into some soup for her husband. Charles took a few sips and fell immediately ill.

A vintage engraving showing Charles's mother tending to her dying son, while a servant inspecting a bottle for signs of misdeeds. Photo: Leemage / Prisma Archive

Ann disclosed her suspicions to the family. When they learned that Charles's servant and gardener had bought arsenic for Marie, Charles’s mother panicked, but Marie replied that it was for killing the rats. Meanwhile, Charles’s condition deteriorated rapidly and he died on January 14, 1840.

Charles's brother-in-law registered a police complaint, and soon the justice of the peace arrived from Brive for questioning. The police took possession of the soup, the sugar water and the eggnog that Anna had carefully put aside. They also found rat poison paste all over the house, but curiously, these were untouched by the rats. The police collected the rat poison as well and sent it away to be analyzed. The results showed that the paste was nothing more than a mixture of flour, water and soda, indicating that the real arsenic was used for something else. Any remaining doubts that may have lingered vanished when a family member produced the box where Marie kept her powdered “sugar”, and the sugar turned out to be arsenic. Marie was arrested.

While Marie’s lawyers were preparing her defense, Marie was accused of another crime from her past. One of her childhood friend, the Viscountess de Léautaud, alleged that Marie had stolen her diamond-studded necklace when she was a guest at her chateau. At that time, the Viscountess did not pursue the matter, but in the wake of the newspaper stories regarding the murder, the Viscount was reminded of the theft and demanded that Marie's room in Le Glandier be searched. A search was conducted and the missing jewels were recovered. A court subsequently sentenced her to two years imprisonment.

Meanwhile, local experts collected contents from Charles’s stomach and carried out several tests for arsenic, but the results were inclusive. While one test yielded a positive result for arsenic, a subsequent test by another group of experts failed to find any traces of arsenic in the victim’s digestive tract. In view of these contradictory results, the judge ordered a third test. Charles’s body was exhumed and new samples were collected from the partially rotten corpse. Again no traces of arsenic was found. When it was reported in court that no evidence of arsenic in the corpse was found, Marie, who had a flair for drama, clasped her hands and raised her eyes to the heaven, and then pretended to faint. She had to be carried out of the court.

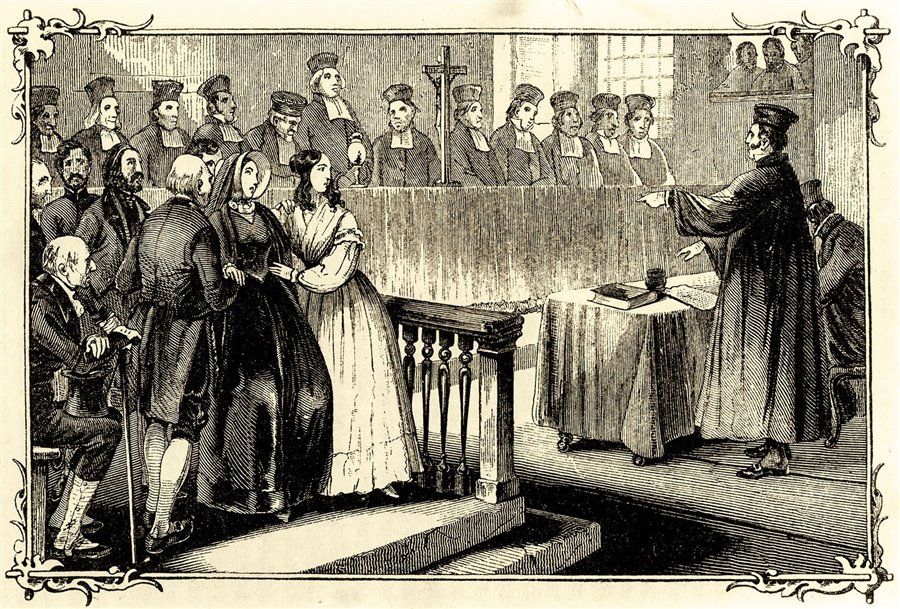

Marie Lafarge at the trial. Photo: AKG / Album

The defense demanded that Marie be released, but the prosecutors pressed on. They produced the eggnog that Anna had carefully stowed away and requested that tests be performed on that as well. This time the chemists declared that the eggnog contained enough arsenic “to poison ten persons.”

As all of this played out in the courtroom, newspaper reporters provided a stream of stories and Marie’s trial became a media sensation. The French citizens became divided on the case. Some believed Marie was a murderer, while others expressed support. Many wealthy gentlemen offered her marriage proposals, or at the very least, financial assistance with her defense. Even young women sent her sympathetic notes. Marie perpetuated her romantic image, answering as many letters as possible, and referring to herself as "the poor slandered one." She would appear in court dressed in mourning and carrying a bottle of smelling salts in her hand to project the image of a woman unjustly accused.

With different medical analysts giving different reports on the evidence, the court decided to consult Mathieu Orfila, an eminent professor of forensic medicine and a renowned toxicologist, and summoned him from Paris. Orfila conducted Marsh tests on samples taken from Charles's body and found definitive traces of arsenic. Orfila also showed that the arsenic did not come from the surrounding soil, nor did it belong to the arsenic naturally present in the human body. Orfila explained that the preceding tests gave misleading results because the tests were performed incorrectly.

After Orfila presented his findings, Marie Lafarge was convicted and was sentenced to life imprisonment. She became the first person to be convicted largely on direct forensic toxicological evidence.

Even after the verdict, many felt Marie was a victim of injustice, convicted by scientific evidence of uncertain validity. As if to defend himself from these criticisms, Orfila conducted well-attended public lectures in the following months, often in the presence of members of the Academy of Medicine of Paris, to explain his views on the Marsh test. Soon, public awareness of the test was such that it was performed live in salons and even in some plays recreating the Lafarge case.

Marie became stricken with tuberculosis, and in June 1852, she was released from the prison by Napoleon III. She died five months later.

Quite a long life in prison, being released in June 1952. Also wasn't Napoleon dead since 1873 already?

ReplyDeleteNice typo, had me giggling…

Marie was 36 years old when she died in the year 1852. This article mistakenly has 1952 as the year of her death which would of made her 136 years old.

ReplyDelete