In the 19th century, a mysterious illness struck rural New England. Those affected had hacking coughs, a wasting fever and weight loss. The disease was known as "consumption" because of the way it literally consumed people from the inside out, gradually making them weaker, paler, and more lifeless until they died. Today, we know it as tuberculosis, an infectious disease caused by a bacteria that generally attacks the lungs. But back then, the prime suspect was vampires.

A sickly girl reclines on a chaise lounge while being attended to by three other women. Watercolor by R.H. Giles.

It doesn’t take much imagination to understand why a bacterial disease came to be associated with vampires. Although tuberculosis or consumption has been around since at least 5000 BCE, it was poorly understood because it can look very different from person to person. In some people, the disease remains latent for years before they fall sick. In others, tuberculosis hits them hard and fast and they die soon after. Symptoms of tuberculosis include wasting, night sweats, and fatigue, and a persistent cough. As the disease progresses, the lungs aren’t able to support the oxygen supply. Their muscles atrophy. Eventually, they start coughing up blood. It was the blood that helped solidify the diagnosis, and the gradual wasting away as if something or someone was sucking the life force out of the person.

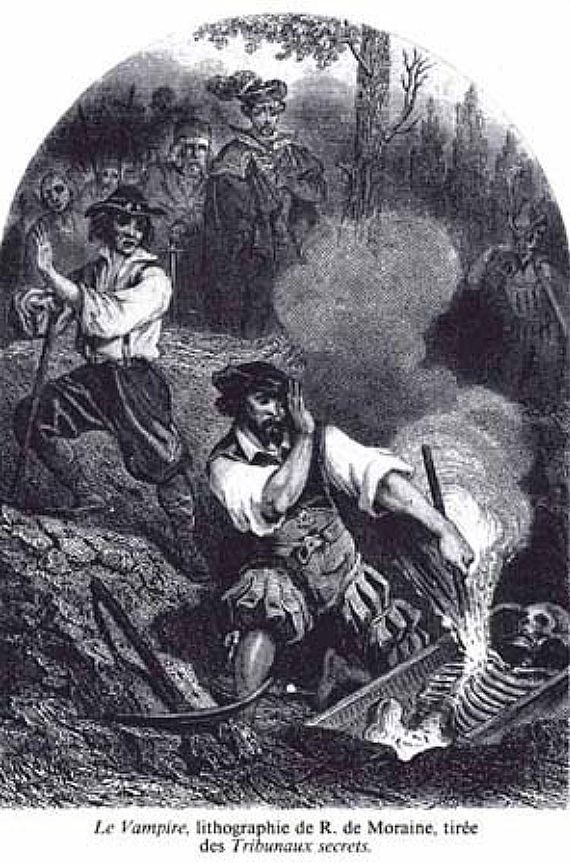

Consumption appeared to run in families because of how easily and rapidly the disease spread. If one member became ill or passed away, the others did too. People believed that one of the dead was a vampire, who was preying upon the surviving family members. Exhumations were frequently necessary to halt the vampire's predations.

The bodies of the dead were dug up and examined for tell-tale signs of vampirism, such as lack of decomposition and the presence of fresh blood in the heart and other organs. After the culprit was identified, a number of different ways were proposed to stop the attacks. The most benign of these was simply to turn the body over in its grave. In other cases, families would burn the "fresh" organs and rebury the body. Sometimes, the body would be decapitated. Others would torch the heart of the alleged vampire and the affected family members would then inhale the smoke or consume the ashes in a further attempt to cure the consumption.

Exhuming a vampire. Photo: Wikimedia

One of the earliest known cases of New England vampirism was that of Rachel Harris, who died of tuberculosis in 1790. A year after her death, her widower, Captain Isaac Burton, married her stepsister, Hulda. Soon after, Hulda began to exhibit symptoms identical to Rachel's, and family and friends concluded that Rachel was to blame. In February 1793, Rachel’s body was exhumed and her liver, heart, and lungs were taken out and burned on a blacksmith's forge. Her exhumation was attended by more than five hundred people. Some versions of the story say that some of the organs were saved to prepare medicine for Hulda. Regardless, she died in September of that year.

In another early case that occurred in 1796, Cumberland resident Stephen Staples obtained permission from the town council to exhume the body of his 23-year-old daughter, Abigail, who had died of consumption. Shortly after Abigail’s death, her sister, Lavinia, had started showing the familiar symptoms of consumption. Lavinia told of dreams in which her dead sister would come into the room and sit heavily on her chest and draw out her breath. There is no record of what came of the exhumation, or whether Lavinia was cured.

Michael Bell, a Rhode Island folklorist, who has been studying New England vampire exhumations has documented at least 80 cases of exhumations reaching as far back as the late 1700s and as far west as Minnesota. The majority of the exhumations occurred in Rhode Island.

One remarkable case that Bell has discovered is that of Rev. Justus Forward and his daughter Mercy. Rev. Forward had five daughters, of which he had already lost three to consumption. His remaining two daughters, including Mercy, were fighting the illness. One day, while travelling to another town with her father, Mercy began to hemorrhage.

At first Forward was reluctant to open the graves of his deceased family members, but allowed himself to be persuaded if it could save the lives of his living daughters. Forward described in a letter how the ritual went:

...this morning opened the grave of my daughter ... who had died—the last of my three daughters—almost six years ago ... On opening the body, the lungs were not dissolved, but had blood in them, though not fresh, but clotted. The lungs did not appear as we would suppose they would in a body just dead, but far nearer a state of soundness than could be expected. The liver, I am told, was as sound as the lungs. We put the lungs and liver in a separate box, and buried it in the same grave, ten inches or a foot, above the coffin.

The act didn’t save Mercy, but Forward’s other children seemed to recover.

One of the best documented cases of suspected vampirism in New England was that of Mercy Brown. In December 1883, Mary Eliza Brown, the mother of Mercy Brown and the wife of George Brown, died of consumption. Seven months later, her eldest daughter, Mary Olive, followed her mother to her grave. Within a few years, the son, Edwin Brown also became ill. Mercy Lena Brown eventually became ill as well and died in 1892.

Some of the neighbors, likely fearful for their own health, approached George Brown and persuaded him to exhume the corpses of the three dead women. Perhaps one of the three Brown women wasn’t dead after all and instead secretly feasting on the living tissue and blood of Edwin.

The graves of George Brown, his wife Mary Brown and daughter Mercy Brown. Photo: Josh McGinn/Flickr

On the morning of March 17, 1892, a party of men dug up the bodies in the presence of a family doctor. After nearly a decade, Mary Brown’s and Mary Olive’s remains had completely decomposed, but Mercy Brown’s body, which had been dead for only a few months, was in a fairly well-preserved state, thanks to the winter. The doctor cut her open and found organs intact. There was even blood in her heart. Mercy Brown was clearly a vampire and the agent of young Edwin's condition.

As the old-time remedy instructed, Mercy Brown’s heart and liver were cut out and burnt on a rock, and the ashes were mixed with water and given to Edwin to drink. Unfortunately, the cure didn’t work. Edwin passed away two months later.

Ten years after Mercy Brown’s exhumation, German microbiologist Robert Koch discovered that the cause of tuberculosis was not vampires but a bacteria. Koch, who was a strong proponent of the germ theory, proved that specific germs caused specific disease such as anthrax, cholera, and tuberculosis, and are transmitted from one body to another. By the turn of the 20th century, public health measures around sanitation improved that helped contain the spread of the disease, but an immediate cure didn't happen until 1946 with the development of antibiotic streptomycin.

Even after the introduction of antibiotics, some remote communities continued to exhume their dead. The last vampire exhumation that Michael Bell found took place in the mountains of Pennsylvania in 1949.

References:

# Vampire Panic, Science History Institute

# Abigail Tucker, The Great New England Vampire Panic, Smithsonian

# Kyla Cathey, The Mystery Behind the 19th-Century New England Vampire Panic, Mental Floss

# Joe Bills, New England’s Vampire History, New England Today

Comments

Post a Comment