On a hot August afternoon in 1904, with temperatures hovering above the nineties (32 degree centigrade), thirty-two men dressed largely in white t-shirts and shorts gathered at the newly constructed Francis Olympic Field in St. Louis, Missouri. They were about to take part in an event that would go down in history as the worst marathon ever ran.

The 1904 Summer Olympics itself was poorly organized, overshadowed by a larger event taking place in the same city—the St. Louis World’s Fair, also known as the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. The games were originally slated for Chicago, but the organizers of the World’s Fair wrested the games away from the rival city and appended it to the Exposition, reducing the prestigious event to a mere sideshow. Additionally, St. Louis was a second-tier city and difficult to reach, which kept almost all of the top European athletes away. Only 62 athletes representing 10 nations joined the event from outside North America. The rest, amounting to nearly 600 athletes, originated from Canada and the host nation, the majority of which belonged to the latter.

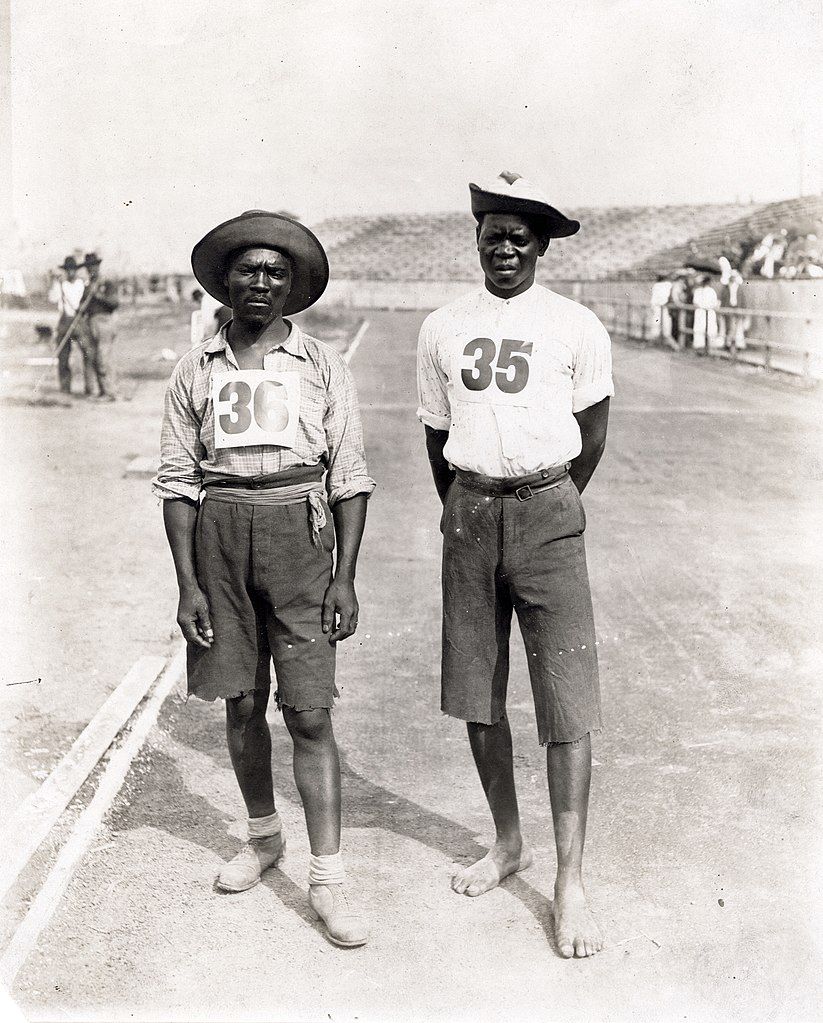

Runners lined up at the start of the 1904 Olympic marathon race.

Of the 32 men who lined up for the 24.85 miles (40 km) marathon, nine were from Greece, one each from France and Cuba, and two from South Africa. Only three had real experience of running long distances, having taken part in the Boston Marathon. The rest were amateurs who had never attempted anything like a marathon in their lives before.

One of the runners, Félix Carbajal from Cuba arrived at the last minutes. Carvajal had traveled to the United States to compete in the Olympic marathon, but lost all of his money gambling in New Orleans, Louisiana, and was forced to hitchhike and walk the rest of the way. He arrived at the race dressed in long trousers, a white shirt and walking shoes. Eventually, a fellow competitor cut off his trousers at the knees in order to make it easier for him to run.

Cubanian athlete Felix Carvajal at the 1904 Olympic Games.

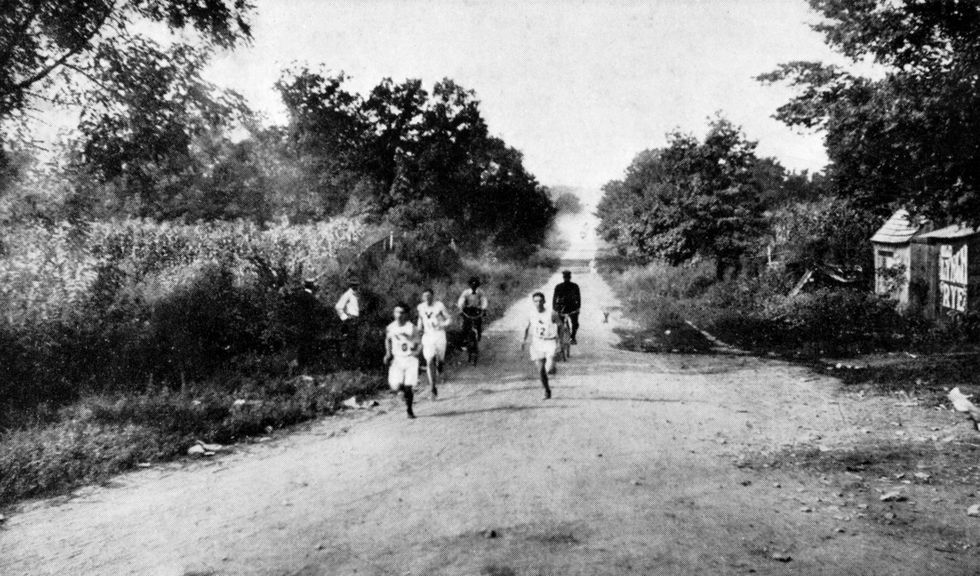

Two other competitors, Len Taunyane and Jan Mashiani, were members of the South African Tswana tribe who were in St. Louis as part of the South African exhibit at the 1904 World's Fair. Both had served as long-distance message runners during the then-recent Boer War. Newspapers reported that both ran barefoot, but at least one of them can be seen wearing shoes in photographs taken during the event. Although the historic importance of their participation was probably unknown at the time, Len Taunyane and Jan Mashiani became the first black Africans to compete in the modern Olympic Games.

Runners Len Taunyane (left) and Jan Mashiani (right) of the Tswana tribe of South Africa before the race.

The race stared at precisely 3:03 p.m during the hottest part of the day. The route traversed through unpaved country roads that kicked up copious amount of dust and made breathing laborious. The men had to constantly dodge cross-town traffic, delivery wagons, and railroad trains, and tackle at least seven hills along the way, varying from 100-to-300 feet high, some with brutally long ascents. To make matter worse, there were only two water stops available on the entire route—one at 6 miles and another at 12 miles. James E. Sullivan, the chief organizer of the Olympics, purposefully wanted to minimize fluid intact to test the limits and effects of “purposeful dehydration”. No wonder, out of 32 runners, only 14 managed to finish the race—the worst ratio of entrants to finishers and by far the slowest winning time, 3:28:45, almost 30 minutes slower than the second slowest winning time.

The first athlete to cross the finish line was Fred Lorz, an American distance runner and bricklayer by profession. Because of his day job, Lorz did all his training at night, and earned his spot in the Olympics by placing in a “special five-mile race” sponsored by the Amateur Athletic Union. Lorz would go on to win the Boston Marathon a year later.

As Lorz sprinted into the stadium for the final lap, the crowd began cheering, “An American won!”. He was about to be presented the gold medal by Alice Roosevelt, the 20-year-old daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt, when someone “called an indignant halt to the proceedings with the charge that Lorz was an impostor”. It later came to light that at the 9 mile mark, Lorz had began suffering from cramps and hitched a ride in a car for the next eleven miles, waving at spectators and fellow runners as he passed. When the car broke down, Lorz jumped out of the vehicle to finish the race on foot in under three hours. When his deceit was called out, Lorz claimed that he finished the race as a “joke” and never intended to accept the honor.

Félix Carvajal—the one who had arrived in street clothes—trotted along at a reasonable pace despite his uncomfortable shoes. Caravajal had reportedly not eaten for 40 hours and was dying from hunger when he saw a spectator eating peaches. He asked if he could have the one, but the spectator refused. Caravajal snatched two and ate them as he ran. A bit further along the course, he stopped at an orchard and snacked on some apples, which turned out to be rotten. Suffering from stomach cramps, he lied down and took a nap. He still finished fourth.

Felix Carvajal on his way at St.Louis Olympic Games' Marathon.

One of the runners, William Garcia of California nearly died when he inhaled dust from the country roads and then suffered a near-fatal stomach haemorrhage. Garcia began coughing up blood and passed out on the side of the road before being discovered and taken to a hospital. Dust had coated his esophagus and ripped his stomach lining. Sam Mellor, who had won the 1902 Boston Marathon, was also overcome by the dust. He dropped out of the race after 16 miles. John Lordan, who had won the 1903 Boston Marathon, started vomiting after 10 miles and too left the race.

South Africa’s Len Taunyane had proved to be a very able runner and was well positioned until a pack of wild dogs chased him a mile off course, leaving him to finish ninth of the 14 finishers. His fellow South African, Jan Mashiani, finished 12th.

Also read: Anthropology Days: The Racist Olympic Event of 1904

The race was eventually won by Thomas Hicks, but he had to be coaxed and assisted by his trainers at various points along the route. At the 10-mile-mark, Hicks began to grow desperately thirsty. He begged them for a drink but they refused, instead sponging out his mouth with warm distilled water. Seven miles from the finish line, Hicks felt his legs giving away when the trainers decided to feed him some egg whites and a pinch of strychnine sulfate. In high doses, this compound is used as rat poison. But at small doses, it is a stimulant. Thus Hicks became the first athletic to use performance-enhancing drug in the Olympics.

With only two miles remaining, Hicks received his second dose of strychnine and some brandy. With strychnine coursing through his veins, Hicks forced himself to walk up the first of the last two hills. By this point, Hicks was hallucinating and believed he still had 20 miles to go. He begged for something to eat and to lie down.

Tom Hicks and his trainers at the marathon.

“Over the last two miles of the road,” wrote race official Charles Lucas, “Hicks was running mechanically, like a well-oiled piece of machinery. His eyes were dull, lusterless; the ashen color of his face and skin had deepened; his arms appeared as weights well tied down; he could scarcely lift his legs, while his knees were almost stiff.”

Finally, when Hicks swung into the stadium, he had to be literally carried over the line. His trainers held him aloft while Hicks moved his feet back and forth, as if he was running. He was declared the winner.

Hicks had lost eight pounds during the course of the race, and declared, “Never in my life have I run such a touch course. The terrific hills simply tear a man to pieces.”

Two days after its running, the Post-Dispatch dubbed the marathon a “man-killing event” and called for the removal of the race from future Games. James Sullivan also publicly decried it and told the paper that “a 25-mile run...is asking too much of human endurance.” Mind you, it was that same James Sullivan who postulated that drinking water during a race was not beneficial, and insisted on only two watering stops throughout the course.

Hicks continued to run marathons for the next five years, before moving to Winnipeg, Canada with his two brothers. Carvajal returned to St. Louis the following year to run in the inaugural All-Western Marathon, where he finished third. He gained sponsorship from the Greek government to run a marathon in Athens Olympics in 1906. However, he disappeared after landing in Italy, and never arrived in Athens. He was proclaimed dead in his home country, only for him the return a year later. He eventually turned professional and went on to defeat American distance runner Henry W. Shelton in a six-hour race in 1907.

Fred Lorz, who almost bagged the gold medal fraudulently, went on to win the 1905 Boston Marathon fair and square.

References:

# Karen Abbott, The 1904 Olympic Marathon May Have Been the Strangest Ever, Smithsonian

# St. Louis marathon: The strangest race in Olympic history, Olympics.com

# Ashwin Rodrigues, The Unbelievable True Story of the Craziest Olympic Marathon, Runners World

Fantastic story! Things have certainly changed.

ReplyDelete