Alexandre Dumas’s literary classic The Count of Monte Cristo is one of Dumas’s most famous and beloved novels, but this satisfying tale of injustice and vengeance was not entirely drawn from the imagination of Dumas. The story was based on a real-life person named Pierre Picaud, who, like Edmond Dantes, was wrongfully imprisoned based on false accusations. Later, Picaud got of prison and after recovering a buried treasure, returned to Paris to exact revenge upon his three jealous friends who implicated him in the conspiracy.

François “Pierre” Picaud was a shoemaker in Nîmes, France. In 1807, Picaud was engaged to marry a rich and beautiful woman named Marguerite Vigoroux. But one of his friends, Mathieu Loupian, who wanted to marry Vigoroux himself, became jealous of his good fortune. Together with two other men, Solari and Chaubart, Loupian falsely accuse Picaud of being a spy and a royalist agent in the pay of England. A fourth friend, Antoine Allut, knew of the conspiracy but did not alert it.

On his wedding day, Picaud was arrested and taken to prison under great secrecy. He spent seven years at the Alpine fortress of Fenestrelle (now in Piedmont, Italy), not even learning why he was arrested until his second year. During his imprisonment, Picaud dug a small passage to a neighboring cell and befriended an Italian priest named Father Torri, who was detained there. A year later, a dying Torri bequeathed to Picaud a treasure he had hidden in Milan.

When Picaud was released after the fall of the French Imperial government in 1814, he took possession of the treasure, and returned to Paris under another name. He spent the next ten years plotting revenge against his former friends. First, he found Allut in Nimes, who in exchange for a large diamond, told him the story of his denunciation. In particular, he learnt that Loupian had bought a café on the Boulevard des Italiens thanks to the dowry of Marguerite Vigoroux, whom he married two years after Picaud’s arrest.

Picaud first murdered Chaubart by sticking a dagger into his heart. He then tricked Loupian's daughter into marrying a criminal, whom he then had arrested, thus dishonoring the name of Loupian’s family. Picaud then burned down Loupian's restaurant, leaving Loupian impoverished. Next, he fatally poisoned Solari and either manipulated Loupian's son into stealing some gold jewelry or framed him for committing the crime. The boy was sent to jail, and Picaud stabbed Loupian to death.

Allut, who became aware of Picaud’s doing, had him abducted and demanded money. When Picaud refused, Allut wounded him fatally. A dying Picaud was eventually found by the French police, and they recorded his confession before he died of his injuries. In 1828, taking refuge in a poor district of London, Allut, ill and dying, summoned a French priest and dictated the whole story to him before dying.

Alexandre Dumas

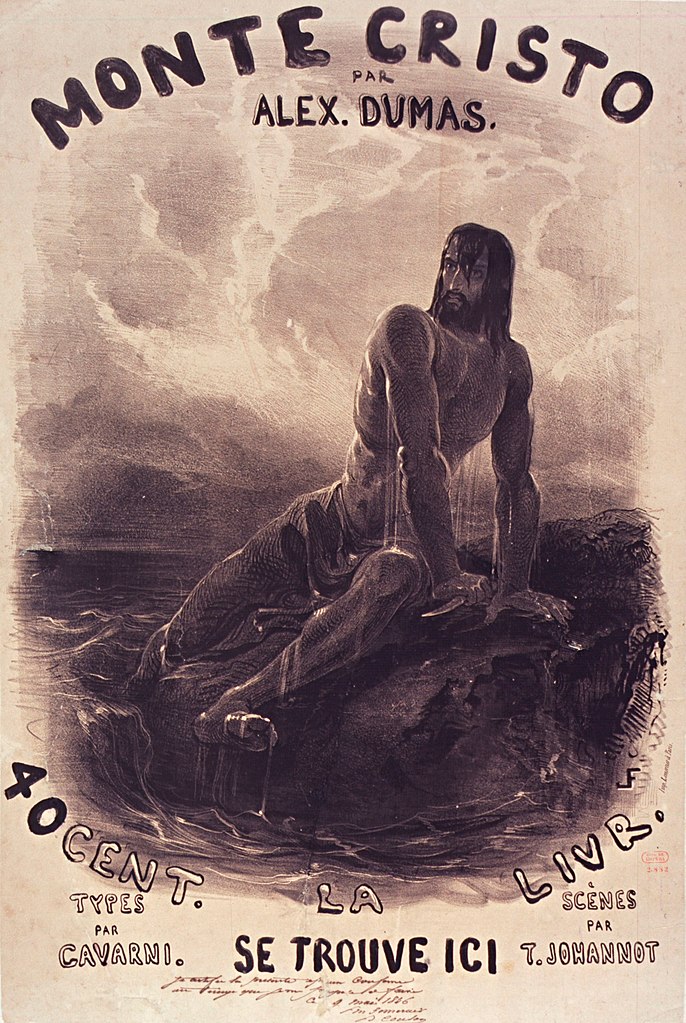

The tale first appeared in “Memoirs from the archives of the Paris police” written by Jacques Peuchet, published in 1838. Alexandre Dumas came across the story and was so fascinated by it that it inspired him to write The Count of Monet Cristo, where Pierre Picaud was immortalized as Edmond Dantes. Dumas acknowledged this in a note titled “Pierre Picaud: Contemporary History”, which appeared as an appendix to the novel.

Historians, however, question the authenticity of the tale. For one, the story is too fantastic. Secondly, there are no records of Pierre Picaud anywhere in the police archives. It appears that the story which Alexandre Dumas considered to be true is actually fiction created by Jacques Peuchet to romanticize the police archives.

The archives itself were destroyed in a fire in 1871. Given the impossibility of going back to the source, some scholars have hypothesized that Peuchet's Mémoires were actually the work of Étienne-Léon de Lamothe-Langon, a French writer known for his many apocryphal memoirs and controversial historical work.

Nevertheless, The Count of Monet Cristo is an absolutely riveting tale about the power of friendship and revenge that is still widely read today.

Comments

Post a Comment