The Manhattan project that developed and built the world’s first atomic weapon employed some 130,000 people, of which only a small number of women worked as scientists at the famous Los Alamos laboratories in New Mexico. Most of the women and men recruited worked as plant operators who did not know what they were working on until after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. Among them were thousands of young women with minimal education and no prior work experience who ran complex machines that separated weapons-grade uranium 235 from uranium 238. They were called the Calutron Girls.

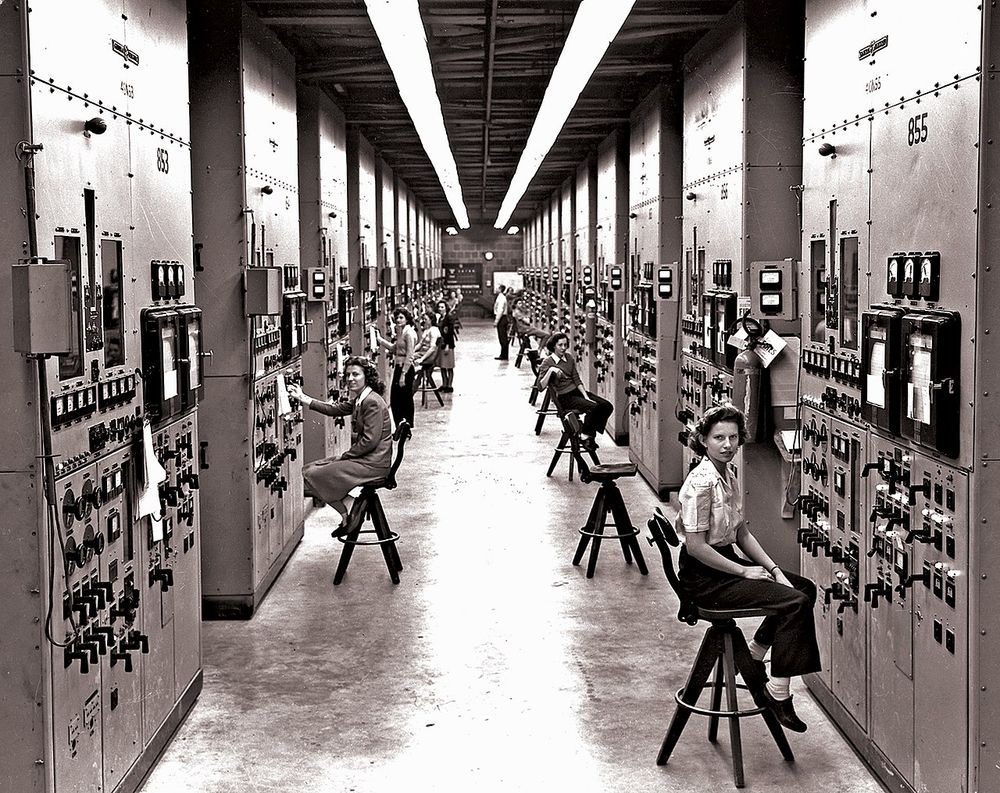

Calutron operators at their panels. Photo: James E. Westcott

Calutron—short for California University Cyclotron—were mass spectrometers that were used in an industrial scale at the Y-12 uranium enrichment plant at the Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Each calutron consisted of a vacuum chamber sandwiched between two magnets. When a beam of charged U-235 and the U-238 ions were shot through the vacuum chamber, because of their different masses, the magnetic fields caused them to separate and deflect at different angles and become trapped in different collectors.

Historian Ray Smith compares U-235 to a ping pong ball and U-238 to a golf ball. If both are attached to two long rubber bands and swung at the same time in an arc, the golf ball, being heavier than the ping-pong ball, would stretch that rubber band farther than the ping-pong ball. Both balls will thus end up at different points at the top of the arc because of centrifugal force.

A Calutron Girl monitoring gauges and adjusting various controls. Photo: James E. Westcott

When calutrons were first developed at the University of California, initially they were operated only by scientists and PhD holders whose job was to remove bugs and achieve a reasonable operating rate. After the calutron had been tuned, operation became fairly simple, but it required constant human monitoring—a task that any person could do with a few basic training.

After the operation of the Y-12 plant was handed over to the Tennessee Eastman Company, the company recruited large number of young women to run the machines. Y-12 supervisors found that young women were better at monitoring the calutrons than the highly educated men who used to operate the machines.

“If something went wrong with the calutron, male scientists would try to figure out the cause of the problem, while women saved time by simply alerting a supervisor,” wrote Explore Oak Ridge. “Additionally, scientists were guilty of fiddling with the dials too much, while women only adjusted them when necessary.”

Women workers leaving Y-12 complex after a change in shift. Photo: James E. Westcott

The girls worked in three eight-hour shifts—7 a.m. to 3 p.m., 3 to 11 p.m. and 11 p.m. to 7 a.m. Their jobs were to sit on tall, hard, wooden stools and adjust handles, knobs and switches while monitoring meters to ensure that the pointer stayed in a narrow range on the dial. The knobs were labeled with cryptic letters. The women did not know what the letters stood for, but they learned rules such as “if you got your M voltage up and your G voltage up, then Product would hit the birdcage in the E box at the top of the unit and if that happened, you'd get the Q and R you wanted”. If the needle went too far off and they couldn’t get it back to where it was supposed to be, they had to call someone else to come help.

The women worked with utmost secrecy even though they didn’t know what kind of information they were protecting. A former Calutron Girl Gladys Owens recalled her manager telling the team, “We can train you how to do what is needed, but cannot tell you what you are doing. I can only tell you that if our enemies beat us to it, God have mercy on us!”

A billboard encouraging secrecy amongst Oak Ridge workers. Photo: James E. Westcott

“What you learn here and what you do here stays here,” recalled Ruth Huddleston, another former Calutron Girl, being told by her employer. “Don’t tell your family. Don’t tell your friends. All you need to know is that you’re working to help end the war.”

Despite being kept in the dark, the women knew that something strange was happening. The control room where the girls worked had strong magnetic fields that pulled bobby pins out of their hair and tugged at screwdrivers in their pockets. People frequently lost their rings, watches and their belt buckles

The Calutron Girls (called Cubicle Operators at the time) were forbidden from discussing their work with anyone. Those who asked too many questions or were caught talking about their jobs soon disappeared. When one young woman did not return to Gladys Owens’ dormitory, her neighbors were told that she had “died from drinking some poison moonshine.”

Calutron Girls at their panels. Photo: James E. Westcott

In two years the calutrons at Y-12 had produced about 64 kg of U-235, enough to make the first atomic bomb. On August 6, 1945, after the US dropped the first bomb on Hiroshima, the Calutron Girls were finally told what they had been working on.

Having realized the part they have played in creating the bomb, many Calutron workers retained mixed feelings about their role due to the devastating loss life in Japan. “I found out the day after they bombed Japan that we had a part in it,” Ruth Huddleston later reflected. “We were producing uranium. I felt like I had a part in helping end the war, but I kept thinking I had a part in killing those people, that’s the part that bothered me. But then I knew that in war there’s killing, and I had to weigh that over and over in my mind to tell myself that and I accepted it. I still think about it.”

References:

# Who Were the Calutron Girls of Oak Ridge?, Explore Oak Ridge

# Atomic bombs dropped 75 years ago: A 'Calutron Girl' remembers, Oakridger

# Calutron Girls, Tennessee Encyclopedia

# Girl Power, Circa 1940: Building The Bomb (and Not Knowing It) in East Tennessee, Blue Ridge Country

Thanks for an interesting article. The first atomic bomb used plutonium not U-235. The Pu-239 was made at the Hanford reactor in Washington state. The second bomb at Hiroshima used the bomb-grade U-235 separated out from U-238 at Oak Ridge. I would be horrified too if I had helped build a bomb, even I was told what I was doing. And I am horrified by the trillions of dollars still being spent by secret militarized governments to build baubles that can never be used.

ReplyDelete