Prickly pear is a common name that refers to a number of large cactus species of the Cactaceae family that is endemic to the Americas. The shrubby, spine-covered plant grows to over twenty feet tall, and given the chance they would quickly colonize any hot, open lands with sandy soil.

The prickly pear is considered an invasive species in most parts of the world, but Governor Phillip at Port Jackson wouldn’t have known that when he authorized the introduction of prickly pear to the British colonies in Australia in the late 18th century.

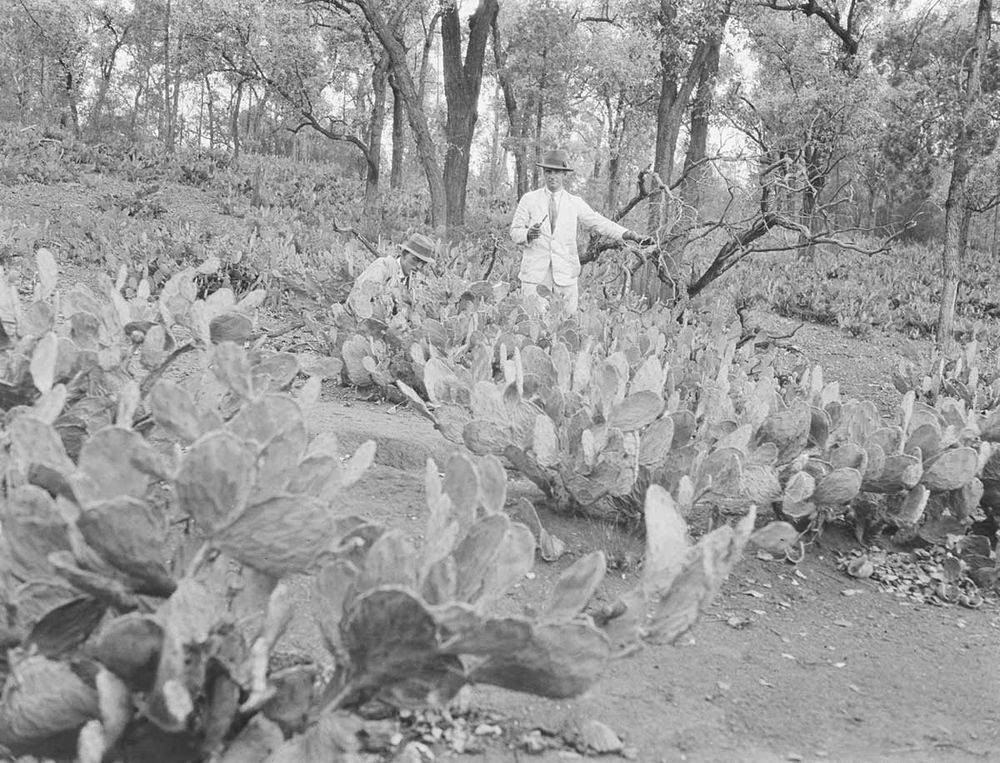

A property in Chinchilla, Queensland, Australia, infested with prickly pear in 1928. Photo: State Library of Queensland/Flickr

Prickly pear has no use to humans, but the cochineal insect (Dactylopius coccus), that feeds on the plant, was once critical to the dye industry. Cochineal insects were crushed to produce one of the brightest red dyes in the world. This dye was used by the natives in North and Central America for centuries before Spanish conquistadors discovered it in the 16th century. Spain quickly established a monopoly on the distribution of the dye in Europe. During the colonial period it became Mexico’s second most valuable export after silver.

Britain wanted a share of the pie, and in the late 18th century botanist Joseph Banks suggested establishing a cochineal dye industry in the subtropical colony of New South Wales.

The first batch of prickly pear plants (most likely Opuntia monacantha) arrived in Australia in 1788 followed by more species, and by 1840 there was a thriving plantation in Parramatta, New South Wales, which had spread to Chinchilla in Queensland by 1843.

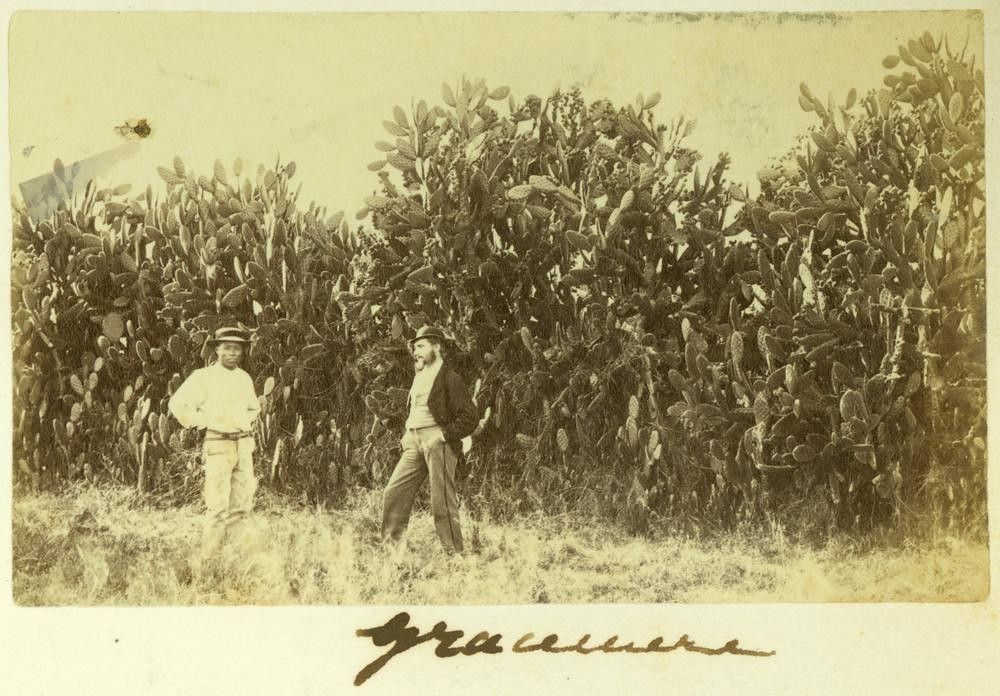

Prickly pear hedges on the property at Gracemere, Queensland, ca. 1872. Photo: State Library of Queensland/Flickr

Opuntia’s seeds are dispersed mainly by animals and birds that feed on its fruit. The tough, coated seeds pass undamaged through the digestive system of these vectors, and once the seed is out of the body, it germinates and a new infestation takes root. Plant segments are also easily detached from the parent plant by animals, wind or flood water and transported elsewhere. It is believed that the flood of 1893 spread seed and plant parts to many new areas. Settlers also took plants to their properties across Queensland and New South Wales to be used as hedges and fodder during droughts, causing the weed to spread throughout the country destroying millions of hectares of agricultural land.

By the 1880s, prickly pear was infesting farmland so badly that farmers began abandoning their land. In 1886, the New South Wales Government passed the Prickly-pear Destruction Act, making people responsible for destroying the prickly pear on their properties. More acts were introduced in 1901 and 1924, but none of the Acts were able to halt the advance of the prickly pear. In 1901 the Queensland Government offered a £5000 reward for anyone who could develop an effective system to destroy the cacti. The reward was doubled in 1907.

Very tall prickly pear infestation in Helidon, Queensland, ca. 1911. Photo: State Library of Queensland/Flickr

Photo: Queensland State Archives

A property in Chinchilla District, 1920s, completely overgrown with prickly pears. Photo: State Library of Queensland/Flickr

Prickly pear over 20 feet high in the Gogango Range, Central Queensland. Photo: State Library of Queensland/Flickr

A stack of cactus to be burned.

People tried to burn the plant, dig them out of the ground and crush them with rollers drawn by horses and bullocks, but none of these methods worked. Others tried chemicals such as arsenic pentoxide, an extremely toxic compound, that was also expensive and hazardous to operate and stock. The demand for arsenic rose leading to the creation of a new industry—of arsenic mining in Queensland at Jibbenbar.

The 1926 Queensland Prickly Pear Land Commission reported that 31,100 tins of arsenic pentoxide and 27,950 tins of Robert’s Improved Pear Poison (which consisted of a mixture of 80 per cent sulphuric acid and 20 per cent arsenic pentoxide) had been sold. But the prickly pear continued to spread until it had choked 240,000 sq.km of land—an area equivalent to the size of the UK.

In 1912, the Queensland Government instituted a Prickly Pear Travelling Commission, consisting of a team of biologists, who travelled to North and South America where prickly pear was indigenous in order to study the cacti’s natural enemy and to investigate the possibility of their use in controlling the cacti’s growth in Queensland.

Explorer and author Michael Terry standing in a patch of prickly pear. Photo: National Museum Australia

The commission identified several species of insects and fungus diseases that seemed to attack the prickly pear. In 1914, the commission brought some of these promising insect species home. One of these insects, the cochineal, was released in a field test. Within three years, the insect had destroyed most of the prickly pear growth.

Further tests with these biological agents were put on hold after the First World War broke out in August 1914. After the end of the war, in 1920, the Commonwealth, Queensland and New South Wales Governments established the Commonwealth Prickly-Pear Board (CPPB) to conduct more research into biological control agents.

The board identified Cactoblastis cactorum , a moth, as the most effective control agent. The female moth lays their eggs on the prickly pear plants. Once the eggs hatch into larvae, they bore into the cactus pad to get at the edible interior. There, they feast on the soft tissues until the cactus pad had been completely hollowed out. A single caterpillar can consume an entire pad in one day. When enough pads had been eaten out, the plants die.

Cactoblastis cactorum. Photo: Wikimedia

In 1925, some 3000 Cactoblastis cactorum eggs were imported from Argentina. These were sent to two breeding and quarantine stations—the Alan Fletcher Research Station in Sherwood, Brisbane and the Chinchilla Prickly Pear Experimental Station—where they were reared. Within a year, the stations had produced 10 million eggs which were distributed throughout the affected areas. A further 2.2 billion eggs were distributed between 1927 and 1931.

The biological experiment at weed control proved to be a spectacular success. By 1932 the moth had caused the general collapse and destruction of most of the original, thick stands of prickly pear, and almost 7 million hectares of previously infested land was made available to settlers. Townships that had been stagnant in the 1920s sprang back to life. At Boonarga, a small settlement west of Dalby, residents built a district hall in memory of the insect and named it the ‘Cactoblastis Memorial Hall’. There is also a monument to Cactoblastis cactorum in Dalby, Queensland commemorating the eradication of the prickly pear in the region.

Property infestation before the release of cactoblastis. Photo: The State of Queensland, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

The same property following cactoblastis release. Photo: The State of Queensland, Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

After the success of Cactoblastis cactorum in controlling prickly pear growth in Australia, the insect was introduced in several other countries where prickly pear was a problem. This developed into a new problem when the moth was released in the Caribbean. Aside from Opuntia, it began to attack other species of cacti as well as and is now considered a major threat to cacti population in Mexico and US.

Now some researchers suggest introducing a parasitic wasp to curb the spread of Cactoblastis cactorum in the United States. These wasps, native to South America, lay their eggs in Cactoblastis larvae and eat the larvae from the inside out. But the concern is that the wasp itself can become an invasive species, parasitizing native caterpillars and other native insect larvae.

References:

# The prickly pear story

# Prickly pear eradication, National Museum Australia

A nightmare, but with a happy ending. Good to know about. I appreciate your work.

ReplyDeleteReminds me of the cumulative tale about the old lady who swallowed a fly...

ReplyDeletePrickly pears are of no use? Dude, they're edible and delicious.

ReplyDeleteExactly what I was going to say! I'm amazed that Australia didn't incorporate nopal into its cuisine with this unexpected bounty!

DeleteIt's true what others have said. Prickly pear fruit and nopal are good eating. "Prickly pear has no use to humans" is simply untrue.

Delete