On 3 April 1817, a mysterious woman in her mid-twenties walked into the small English village of Almondsbury in Gloucestershire. She was dressed in a plain black dress with a high muslin collar and a black turban. She appeared to be disoriented and was speaking a language the locals didn’t understand. The woman was visibly exhausted, and she carried with her a small cloth bundle that presumably contained her entire possessions.

The woman was first found by the village cobbler and his wife. Thinking her to be a beggar, they took her to the Overseer of the Poor, a certain Mr. Hill, whose job was to administer poor relief such as money, food and clothing to the poor. Mystified by her strange language, Mr. Hill took her to the local county magistrate, Samuel Worrall, who lived in Knole Park.

Princess Caraboo. Image credit: Wikimedia

Mr. Worrall and his American-born wife Elizabeth could not understand the woman’s language, and neither did their Greek butler. Mrs. Worrall was fascinated by her exotic appearance though, but Mr. Worrall was more cautious. In those years following the Napoleonic Wars mysterious travelers were looked upon with deep suspicion by the authorities for they could be spies or political agitators. Many were arrested and transported to Australia.

Mr. Worrall tried to communicate with the girl using signs and asked her for any papers she might have. But the girl didn’t have any. She emptied her pockets, and out popped a few halfpennies and a fake sixpence. Carrying counterfeit money was a serious crime and attracted the death sentence. But the girl did not seem to understand the seriousness of these offences.

Believing that the girl was from a distant land and unfamiliar with the laws of England, the Worralls decided to take her in for the night. They sent her, in the company of two of their servants, to the village inn called The Bowl. At the inn she noticed a print of a pineapple on the wall and pointing to it excitedly, cried “anana”, which was similar to “nanas”, the Indonesian word for pineapple. The hosts were convinced that the exotic fruit was from the mysterious stranger’s homeland and assumed her to be from Asia.

The inn where Princess Caraboo spent her first night at Almondsbury. Photo: Adrian Pingstone/Wikimedia

The landlady then offered to cook her supper, but the girl indicated that she would rather have tea. When presented with a cup, the girl uttered a small prayer while holding one hand over her eyes, and then drank it. When the landlady showed the girl her bed, she seemed unable to understand its function and laid down on the floor instead. Only after the landlady's young daughter demonstrated how comfortable it was, did she appear to understand and lay down on the bed.

Determined to find more about this exotic woman and her strange customs, Mrs. Worrall brought her back to Knole Park to stay. She soon learned that her name was 'Caraboo', and that she had come to England in a ship, but nothing more.

The girl was taken to Bristol to be examined by the mayor and then on to St Peter’s Hospital, which cared for vagrants. But nobody could understand her foreign tongue. By now word had spread of the attractive foreign stranger and curious members of society came to visit Caraboo.

One day, a Portuguese sailor named Manuel Eynesso arrived in the town and after hearing her speak for a few minutes declared that he could understand Caraboo’s language. He spoke with the girl and then told Mr. Worrall that she was a princess from an island called Javasu, who was abducted from her homeland by pirates and held captive on a ship, until she escaped by jumping overboard in the Bristol Channel and swimming to the shore.

A painting of Princess Caraboo by Edward Bird. Photo: Wikimedia

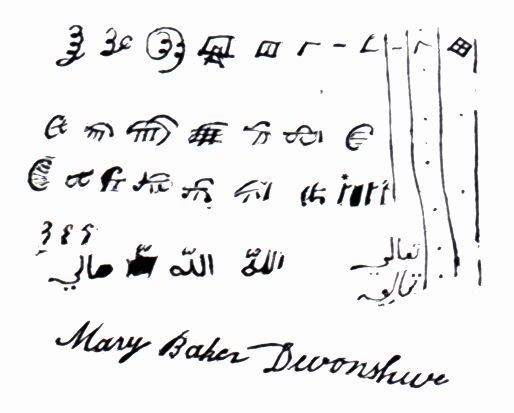

The story fascinated Mr. Worrall and his friends. The news that there was a foreign princess in town spread like wildfire and people came from all around to see her. Princess Caraboo delighted guests with her strange language and eccentric manners. She was a skilled fencer and used a home-made bow and arrow with great proficiency, danced exotically, swam naked in the lake when she was alone, and prayed to her supreme being "Allah Tallah" from treetops. Soon newspapers were full of descriptions of Princess Caraboo, and she became a national figure.

For ten straight weeks, Princess Caraboo enjoyed the best time of her life until a boarding-house keeper, Mrs. Neale, read the description of the princess in the Bristol Journal and recognized her true identity. Princess Caraboo’s real name was Mary Baker (born Mary Willcocks), a cobbler's daughter from Witheridge, Devon. A couple of months earlier, Mary had been a lodger at Mrs. Neal’s, where she sometimes entertained Mrs. Neal’s young daughters by speaking in her own made up language. When she left the house she would wear a turban.

Princess Caraboo pampered by the ladies. Photo: Wikimedia

When confronted with the news, Mary at first denied but eventually broke down and admitted the truth.

Mary Baker was born in 1791 into a very poor family where six of her brothers and sisters had died young. Mary started working at the young age of eight. She spun wool and weaved, and occasionally worked on local farms. Later she worked as maid in various houses in Exeter and London. Many of her employers described her as “odd and eccentric”. She also spent time in St. Mary’s workhouse in London and the Magdalen Hospital for reformed prostitutes, where she worked under false pretense.

Mary lied whenever necessary to gain employment and earn pity, so it was not easy to separate fact from fiction. For instance, she said that once she was walking from London to Devon, disguised as a man for safety, when she was kidnapped by highwaymen on Salisbury Plain. When they discovered she was a girl they were ready to shoot her as a police spy, but she begged for her life and was released. She also claimed to have been married to a man named Baker (from whom she adopted the surname Baker) who then abandoned her. She also appeared to have given birth to a child in 1816, who died shortly after.

She said to have spent the Christmas of 1816 in France, and in February 1817 returned to England to her parents. She told them that she was sailing from Bristol to Indies, but instead ended up begging on the road to Plymouth. After staying with the gypsies for some time, she headed back through Exeter to Bristol. While looking for a ship to take her to Philadelphia, she found lodgings in a house belonging to Mrs. Neale, and spent the days begging in the streets. It was after noticing the attention that French lace-makers from Normandy received wearing high lace headdresses, that Mary decided to use her black shawl as a turban to make her look more interesting.

Script made up by Princess Caraboo. Photo: Wikimedia

Mary soon got tired of Bristol and began to proceed to Gloucester, begging at various places along the road using her own contrived language to disguise her identity. Mary pretended at various times to speak French and sometimes to speak Spanish. Once when pretending that she spoke Spanish, Mary was confronted by a man who said he spoke Spanish, and thus was forced to speak to him in Spanish. Amazingly, the man said he understood. This experience taught Mary an important lesson in how to use the alleged “expertise” of others for her own ends. That night she stayed in a lodge and created a new identity for herself. The very next morning, she headed out towards the village of Almondsbury as the famed Princess Caraboo.

When Mr. Worrall discovered the truth, he was initially shocked, but he couldn’t help but be amazed and filled with admiration at the poor working girl who managed to fool highly intelligent academics for so long. The press made her into a working-class heroine who had deceived high society and exposed upper class vanity. They began to spin their own yarn of how the beautiful Princess Caraboo was on a Philadelphia-bound ship when tempest drove the vessel close to the island of St. Helena where Napoleon was imprisoned. The intrepid princess impulsively cut herself adrift in a small boat, rowed ashore and so fascinated the emperor that he wished to marry her.

Mr. Worrall was a kind-hearted man who took pity on Mary. When she expressed the desire to go to America, he put her on a boat for Philadelphia in the company of three ladies whom Mrs. Worrall had asked to take care of her. When they arrived in America, Mary was greeted by enthusiastic crowds as “Princess Caraboo”, and she gave performances as the Princess while there.

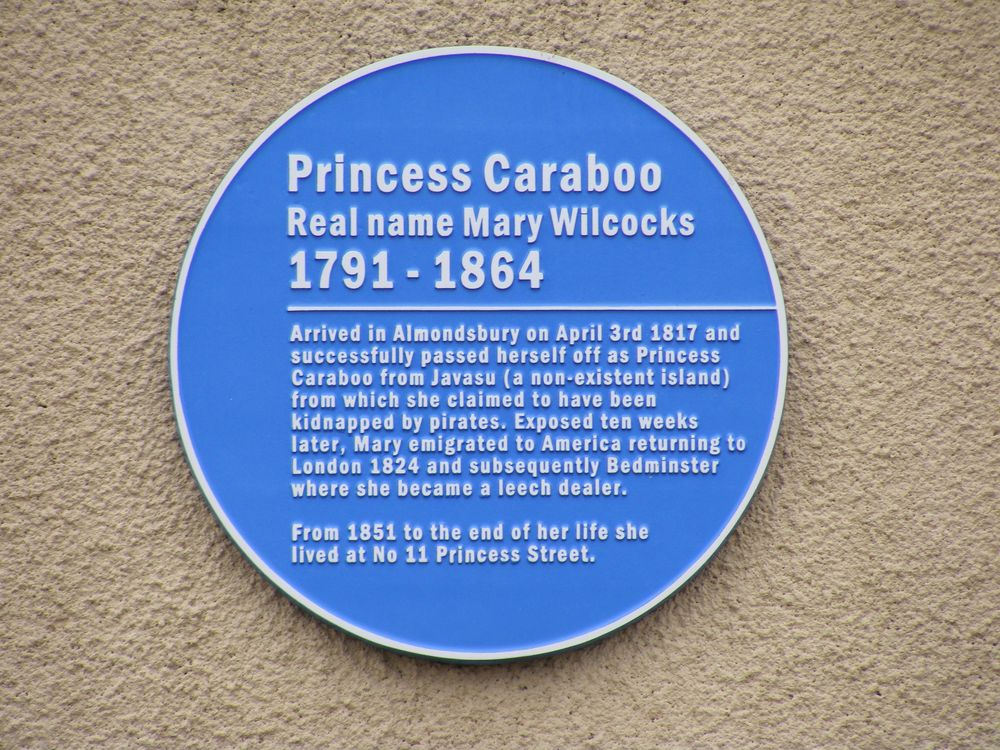

Mary continued to play her character as Princess Caraboo when she returned to England in 1824, exhibiting herself in New Bond Street, London, and later in Bristol and Bath. Mary subsequently travelled in France and Spain, but returned to England to marry and settle down in Bristol, where she had a daughter in 1829. Mary made a decent living selling leeches to Bristol Infirmary Hospital, until she died on Christmas Eve, 1864, at the age of 75. She was buried in the Hebron Road Burial Ground, Bedminster, Bristol, and lies there still, in an unmarked grave.

A blue plaque commemorating Princess Caraboo in Almondsbury. Photo: Open Plaques/Flickr

Comments

Post a Comment