In 1899, the Chicago & Alton Railway introduced a new intercity rail service between Chicago and St. Louis. Pulled by a 4-6-2 steam locomotive, the Alton Limited consisted of six perfectly symmetrical cars, including two Pullman parlor cars, strikingly decorated both inside and outside. The Alton Limited was billed “The Handsomest Train In The World.”

According to the company, no railway train in the world had ever presented a design so uniform and symmetrical. The windows were of the same size, shape and style from the mail car to parlor car. All the cars were mounted on standard six-wheel trucks. Every car in the train had precisely the same length and height, including the tender of its locomotive which was built to the same height as the body of the cars following. Even the hood of the locomotive had the exact height of the roofs of the cars. “This gave a fascinating beauty to the train”, the company pronounced, “carrying out of the principal features with classic regularity—the absolute unity of detail from cow-catcher to observation platform.”

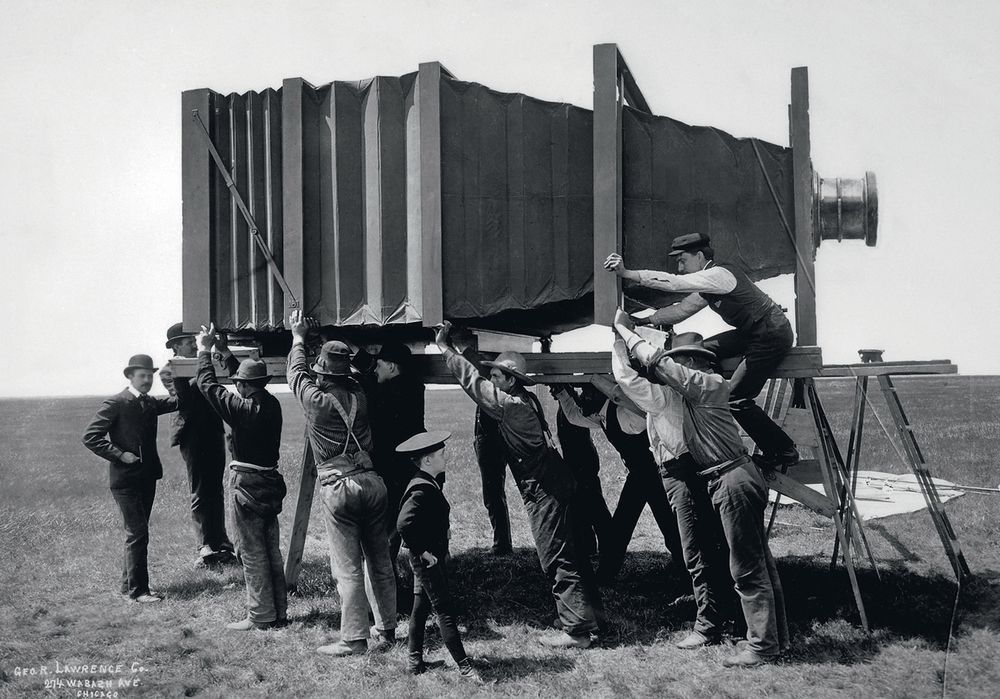

George Lawrence’s Mammoth Camera built to photograph the Alton Limited.

Shortly after the train was built, the company decided to participate in the Paris Exposition of 1900 where they planned to impress the public with the train’s unprecedented symmetry. But rather than ship the entire train to France, the Chicago & Alton Railway decided to create a huge photograph of the train and exhibit it instead. For this task, the company hired George Raymond Lawrence, a remarkable photographer, who ran a studio in Chicago with the slogan: “The hitherto impossible in photography is our specialty.”

The railroad company wanted a picture clicked of their prized creation in its entirety, all in one frame. At first, Lawrence suggested that the train be clicked in section, which would then be joined together during the printing process. But the company rejected the idea; they wanted a flawless picture of their flawless train. They also insisted that the length of the photograph must not be less than eight feet.

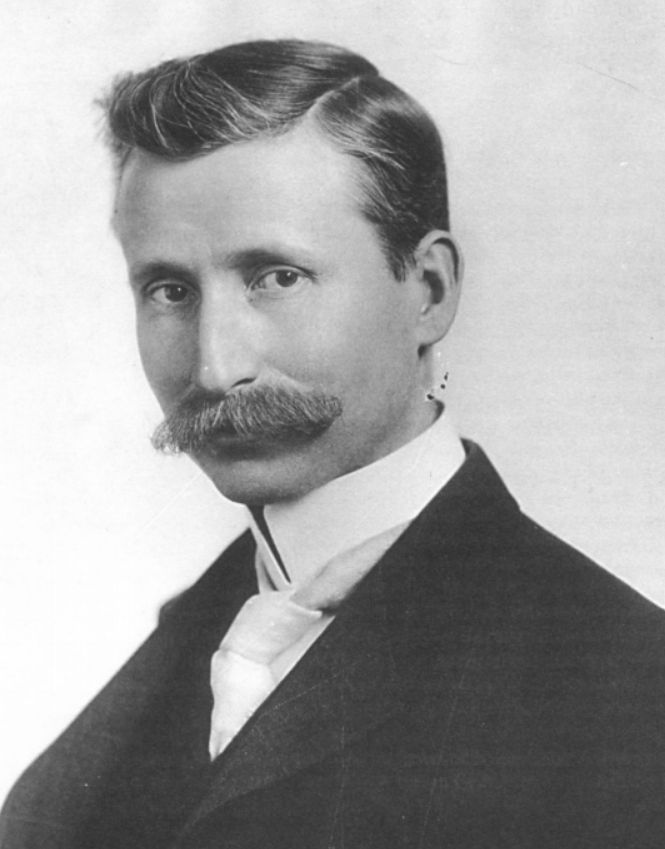

George Raymond Lawrence

Accepting the challenge, Lawrence sought the assistance of camera manufacturer J. A. Anderson, and within eight months, they designed and built the “Mammoth Camera”—a massive contraption weighing 1,400 pounds and requiring fifteen operators. When fully extended on steel-track wheels, the bellows measured twenty feet. The lens were reported as the largest ever built for photographic purposes, and were especially made by the Bausch and Lomb Optical Company of Rochester, New York. Two lens were built; one was a wide-angle of 5.5 feet equivalent focus and the second one was a telescopic rectilinear lens of 10 feet equivalent focus. The camera used an 8 feet by 4.5 feet single glass negative, which was almost three times larger than those used by existing panoramic cameras.

The camera was so large that prior to exposure a man could enter and dust off the plate as follows:

The holder is put in position, the large front board, or front door as it may be called, is swung open, the operator passes inside with a camel's hair duster, the door is then closed and a ruby glass cap placed over the lens, the curtain slide is drawn and the operator dusts the plate in a portable dark room, after which the slide is closed and he passes out the same way as he entered.

In a letter to the editor of Photographic Times, Lawrence's partner, Anderson, described “the largest camera in the world”:

This camera is constructed to allow a full exposure of a plate measuring 56x96, and embodies, in its construction, all the improvements an up-to-date camera can have, being reversible, having double swing back, rising and swinging front, and an arrangement for bracing the back that makes it as rigid as the back of a small camera, thus dispensing with any jar or vibration while an exposure is being made.

In the construction of the four bellows-two cone and two square-there was over fifty yards of heavy black rubber sheeting used, and though they allow an extreme focus of fifteen feet, yet so compact were they made, the whole camera can be folded to three feet.

The holder is curtain slide, and although fifty feet of five eight inch lumber was used for the slide it was made to work so easily that a boy of fourteen years would have no difficulty in drawing it.

As a ground glass for focusing in this mammoth camera would be clumsy to handle and liable to breakage two frames were made to slide on the back of the camera, and celluloid strips made to fit in these frames, making a very light and satisfactory substitute for the usual ground glass.

After months of planning and preparation, on a clear spring morning in 1900, the camera was painstakingly transported by a flatcar to Brighton Park, about six miles from Chicago. From there, a padded van took the camera to a suitable location in an open field. At the distance stood the Alton Limited. After aiming the camera at the motionless train on the tracks, four men inserted the mammoth glass plate while another six operated the bellows and lens. Lawrence removed the lens cap and after an exposure of two-and-a-half minutes, replaced the cap and the exposure was completed.

The Alton Limited photographed by George Raymond Lawrence.

Lawrence made three gargantuan prints from the negative and sent them to Paris to be exhibited at the Exposition. One was hung in the United States Government Building, another in the railway exhibit, and one in the photographic section. At first, the judges in the photography competition were skeptical; no one had seen such a large photograph before. They believed the photograph was a composite and hence a fake. It was only after the French Consul in New York was dispatched to Chicago to verify the existence of the camera and to observe its mode of operation, were the organizers convinced of its authenticity. Eventually, it earned Lawrence the ‘'Grand Prize of the World for Photographic Excellence'.

The Mammoth Camera was just one of many inventions of photographic genius George Raymond Lawrence. His most remarkable exploit was aerial photography where he sent tethered cameras high up in the sky using kites, as opposed to hydrogen-filled balloons, allowing him to take stunning panoramic photographs without exposing himself to the perils of high-altitude ballooning. His most famous aerial photograph was that of San Francisco taken from 2,000 feet above the bay after the devastating earthquake of 1906.

San Francisco in ruins photographed by George Raymond Lawrence.

A train of kites Lawrence used to hoist his camera.

George Lawrence was also a pioneer in flash photography. He invented a flash powder that was brighter and created less smoke than magnesium that photographers normally used. He also set up a system where he could fire multiple flashes simultaneously using electricity, thereby greatly increasing the amount of available light. This allowed him to take large scale indoor photographs with absolute safety. In recognition of these inventions Lawrence received the highest award for artificial light photography from the Photographic Association of America in 1899, as well as the nickname “Flashlight Lawrence”.

Another large-scale photograph by George Lawrence. This unique photo of the Kexholm Regiment of the Russian Empire shows more than 1,000 people, arranged in 25 rows of 50 men each. Lawrence built a camera and the objective with a diameter of about 1 meter for this photograph in 1903.

References:

# The Mammoth Camera Of George R. Lawrence, Simon Baker

# Photography Genius: George R. Lawrence & "The Hitherto Impossible", Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society

Comments

Post a Comment