How do you define a war? Should both sides have a fair chance of winning? Is a coup within a protectorate justified as war? Does the conflict end even if the reigning individual survives amidst desolation and complete destruction of his kingdom? And how short do you think the shortest war in history was? A few minutes, maybe about an hour, a day at large if you account for the mundane details. That’s how long the Anglo-Zanzibar war lasted. Was it fair to call it a war?

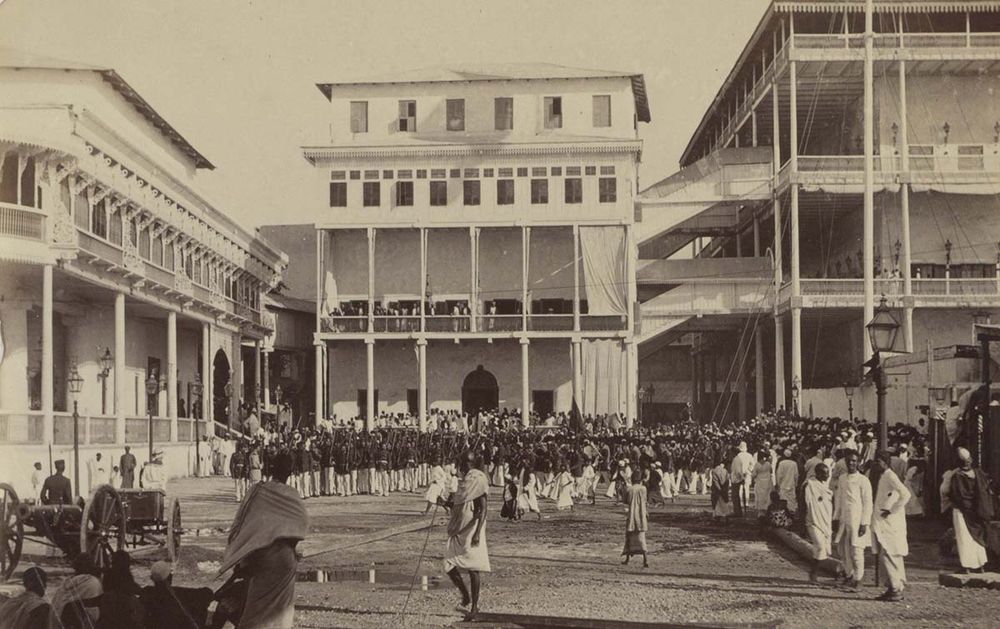

Soldiers at the palace of the Sultan of Zanzibar, circa 1880 –1920.

St Thomas Aquinas answered all these questions in his definition of war. According to him, a war should be just in the reason for its inception as well as in the means with which it is fought. While the justness of the Anglo-Zanzibar tiff floated in murky waters, literally, a sum of its elements designated the conflict as a war alright.

On 25 August 1896, the Sultan of Zanzibar Hamad bin Thuwaini died. His nephew Khalid bin Bargash seized power by force almost immediately. But the imminent war was not among kin. Zanzibar—a tiny island off the East African coast that is now a part of Tanzania—was an independent country where the British had established a protectorate. While the sultan was clearly under their paw, his doubts had made him create an army of 1,000 men that were loyal only to the throne. Upon his passing, the acquiescent Hamud Mohammed was going to be the chosen sultan, but Khalid bin Bargash stole the show, reigning in this military force to his advantage.

A thriving clove industry kept the Anglos deeply interested in the affairs of the state. Naturally, when the royal nephew made it clear that he would not be controlled, they were furious. Moreover, they knew about Khalid’s unequivocal resistance to the abolishment of slavery—a cause his brother had given in to long ago.

Diplomacy was their first go-to option. At 8am chief diplomat Basil Cave issued a formal warning to Khalid, asking him to surrender. To go against direct British orders would mean inviting bombardment of the sultanate for retaliation. Khalid did not leave the palace—not for a while at least.

That evening, Cave wired the Foreign Office asking, “Are we authorised in the event of all attempts at a peaceful solution proving useless, to fire on the Palace from the men-of-war?” With a yes in answer to the blatant rebellion, British troops cruised the waters in their vessels to reach the coastal town. Another warning was issued to Khalid on 26 August, but it wasn’t until the next morning that he replied saying, “We have no intention of hauling down our flag and we do not believe you would open fire on us.”

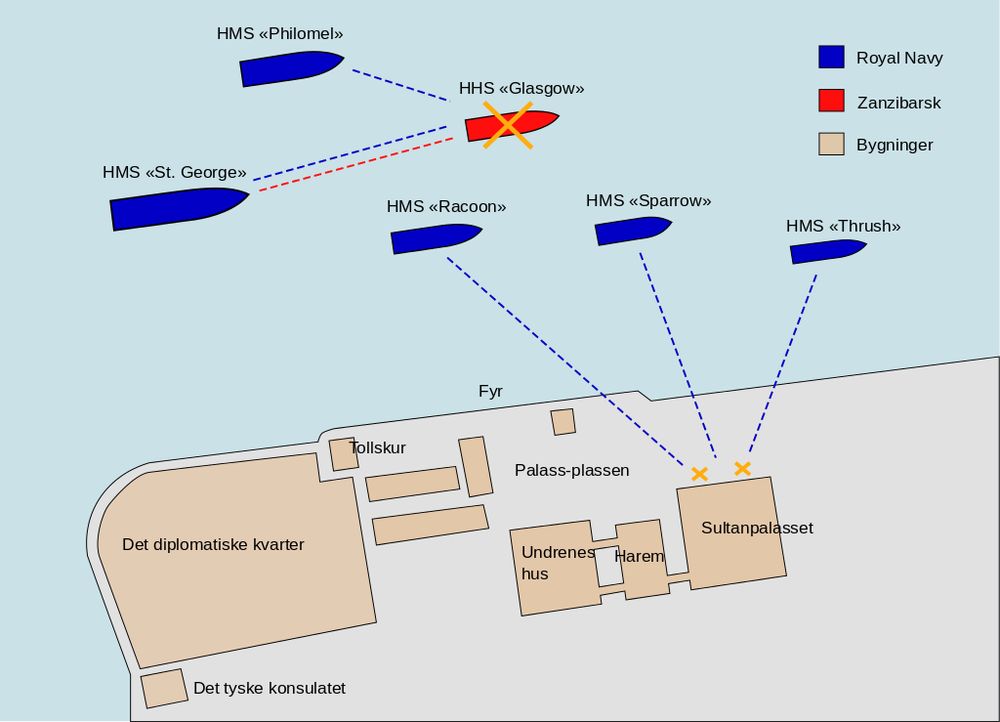

Map showing the disposition of the naval forces and the exchange of fire at the outbreak of the Anglo-Zanzibar War, 27 August 1896. Image credit: PaulVIF/Wikimedia

The Zanzibari forces were prepared with their artillery—most of which had been a gift from the protectorate. Khalid’s insurgent remark had finally declared war. Heavy bombardment ensued, unmatched in size or force by the trickling army of Zanzibar. Their modest numbers were no match to the heavily populated warships of Britain called HMS Philomel and HMS Rush. Backup ships joined the conflict too. Battle shells flooded the coastline and within 30 to 45 minutes the royal yacht had sunk to the water bed, taking down over 500 soldiers and civilians. Only a single British officer was harmed in the duration. The only clocktower in the area was shot down, which was why reports were never able to define the exact duration for which the tryst lasted. But it could not have been north of an hour.

Khalid survived the loss though and fled to the nearby German consulate to seek refuge. From there he was exiled out of the country. The Germans assured the British that they would not be bothered by Khalid, and Hamud bin Muhammed was restored as the chosen leader of the sultanate. According to Hew Strachan, a military historian of Oxford University, “an individual cannot go to war. It is a group activity.” The war survivor then had no leverage left. The battle was over within the day.

Destroyed Palace and other buildings after the attack in the Anglo-Zanzibar War.

The sultanate continued to exist under stringent compliance rules till the 1960s when it was merged with Tanzania. Khalid lived on for years, until dying in British Mombasa in 1927. The next war to come closest to breaking the Anglo-Zanzibar occurred in 1967. It was the Six-Day war which lasted close to a week. None, though, that could be described as briskly as “they came, they saw, they conquered.”

References:

# History-uk.com

# History.org.uk

# Atlas Obscura

# National Geographic

Comments

Post a Comment