In 1883, a Jerusalem antiquities dealer named Moses Wilhelm Shapira announced the discovery of a remarkable artifact—15 fragments of ancient manuscripts written on leather which he claimed had been found near the Dead Sea. The manuscript contained bible verses from the Book of Deuteronomy, but they were slightly different from those used in churches and synagogues. Shapira explained that the different text and the paleo-Hebrew inscription suggested that the manuscripts were older than the Book of Deuteronomy, dating to the period of the First Temple, before the Babylonian Exile. If true, this would make the scrolls the oldest biblical manuscript in the world.

A fragment of a copy of the Shapira scroll prepared in 1883 in consultation with the British scholar Christian David Ginsburg.

Shapira’s claim aroused great public interest and drew newspaper headlines around the world. But experts were skeptical of Shapira’s bold claim. Shapira had a reputation of peddling counterfeit artefacts. A few years earlier, he was caught trying to sell a fake “coffin of Samson” with a misspelling of the name Samson in the epitaph. In another lucrative deal, he sold 1,700 fake figurines, the so-called ‘Moabite forgeries’ to a Berlin museum. With the money earned through this fraudulent transaction, Shapira bought an elegant villa outside the old city walls of Jerusalem.

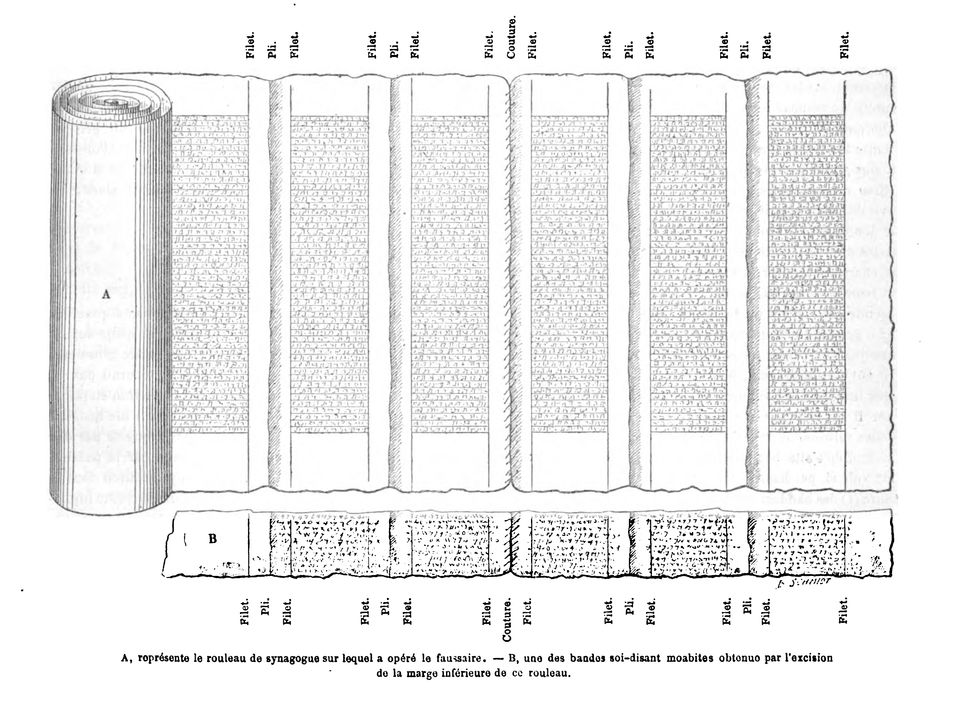

Shapira tried to authenticate his find by sending them copies to various archeologists and scholars in Germany. But their decision was unanimous—the manuscripts were forgeries. The Royal Library of Berlin even offered to buy the scrolls from Shapira so that German students could study the forger's technique. Shapira refused and instead, offered the treasure to the British Museum for a million pounds. The museum put two of the fragments on display, attracting throngs of visitors, including Prime Minister William Gladstone. The rest were sent to prominent bible scholar Christian David Ginsburg for evaluation. Four weeks later, Ginsburg came out with a verdict: the manuscript was a fake. Ginsburg said that Shapira had taken a genuinely old Torah scroll, sliced off its blank lower margin, and inscribed that ancient-looking strip with his own version of Deuteronomy. Ginsburg also indicated that the shape of the strips, their ruling, and the leather used matched Yemenite scrolls Shapira had sold to the Museum previously, suggesting that the Shapira scrolls were possibly cut from the Yemenite scrolls.

The form of Shapira's strips compared to a synagogue scroll margin. An illustration prepared by Clermont-Ganneau

Ginsburg's conclusion drove Shapira to despair, and he fled London. On August 23, 1883, he wrote to Ginsburg:

You have made a fool of me by publishing and exhibiting things you believe to be false. I do not think I shall be able to survive this shame. Although I am not yet convinced that the manuscript is a forgery – unless Monsieur Ganneau did it. I will leave London in a day or two for Berlin.

Yours truly, Moses Wilhelm Shapira

In spite of writing to Ginsburg that he would leave for Berlin, he fled London to Amsterdam instead, leaving the manuscript behind, and from Amsterdam he wrote a letter to Edward Augustus Bond, principal librarian of the British Museum, begging for reconsideration of the manuscript. In both letters, Shapira reaffirmed his belief in the scroll's authenticity. Six months later, he shot himself in a hotel room in Rotterdam.

A couple of years later, the Shapira scrolls appeared in a Sotheby's auction, where it was sold for £10. The scrolls were last seen at a public lecture in Burton-on-Trent in 1889, after which they disappeared for good.

Shapira’s scrolls were nearly forgotten until more than 60 years later when the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered at the Qumran Caves on the shores of the Dead Sea in exactly the same circumstances that Shapira claimed he found his manuscripts, thus igniting a new interest in Shapira’s scrolls. Could those manuscripts have been genuine?

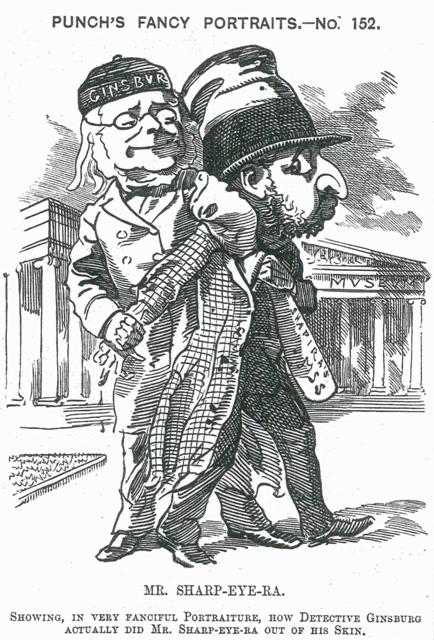

This cartoon appeared in “Punch” following Ginsburg’s verdict.

Idan Dershowitz, a 38-year-old Israeli-American scholar at the University of Potsdam in Germany, believes the manuscript was an authentic ancient artifact—an ancestor of the Book of Deuteronomy.

Dershowitz feels that the dismissal of Shapira’s manuscript nearly 140 years ago was not just a mistake, but “a tragedy” — and not just for Shapira.

“It’s mind-boggling that for almost the entire existence of the discipline of Bible studies, this text that tells us more than any other manuscript discovered before or since hasn’t been part of the conversation,” he said.

Many modern scholars still believe that the scrolls were forged. In “The Lost Book of Moses,” a 2016 book about the Shapira affair, the journalist Chanan Tigay claimed to have found the original leather leaves from which Shapira had sliced off the bottom, just as Ginsburg and later Clermont-Ganneau had speculated. But according to Dershowitz, the Torah scrolls were likely cut off to prevent rot after a water damage, and not to provide material for a forgery.

Dershowitz also traveled to the Berlin State Library to look at Shapira’s papers. There, scattered in a bound volume of jumbled invoices and notes, he found something he said no one had ever noted: three handwritten sheets that appeared to show Shapira trying to decipher the fragments, with many question marks, marginal musings, crossed-out readings and transcription errors.

“It’s amazing because it gives you a window into Shapira’s mind,” Dershowitz said. “If he forged them, or was part of a conspiracy, it makes no sense that he’d be sitting there trying to guess what the text is, and making mistakes while he did it.”

Moses Wilhelm Shapira

Dershowitz found encouragement from many scholars when he presented his findings at a confidential seminar at the Harvard Law School.

Michael Langlois, an epigrapher at the University of Strasbourg who attended the seminar, credited Dershowitz for making the best case yet, even if it remained, in his view, dependent on many hypotheticals. But he noted that when the first Dead Sea Scrolls surfaced in 1947, some leading scholars, mindful of the Shapira fiasco, initially dismissed them as fakes.

“Can you imagine what would have happened if no one had had the guts to consider them authentic?” Langlois said. “We would not even have the Dead Sea Scrolls today.”

Sidnie White Crawford, an epigrapher and Dead Sea Scrolls expert at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, said that without the original fragments Dershowitz’s arguments can’t be proved or disproved, so they “must remain a footnote in the scholarly discussion of the origins of Deuteronomy.”

“The Shapira story is trailed by a tantalizing swirl of what-ifs,” Jennifer Schuessler writes for The New York Times. “What if someone with a less checkered reputation had found the fragments? What if Shapira hadn’t committed suicide? What if they hadn’t been lost — or had first surfaced 80 years later, after the Dead Sea Scrolls, when scholars might have viewed them differently? And of course, what if they really were forgeries?”

"...it makes no sense that he’d be sitting there trying to guess what the text is, and making mistakes while he did it.” Unless that was part of the planned forgery.

ReplyDelete