In the late 1950s, the United States of America launched a new kind of nuclear program called Project Plowshare aimed at finding ways to better utilize the tremendous energy released by nuclear bombs. Until then, nuclear energy meant only one thing—weapons. But scientists wanted to find whether nuclear energy could be used for peaceful purposes such as blasting a new harbor in Alaska, or digging a new canal through the Isthmus of Panama, and other such projects that involved moving large quantities of earth and rocks. One such project was fracking.

Photo taken at ground zero shortly after the detonation on September 10, 1969, Project Rulison. Photo: U.S. Department of Energy

Hydraulic fracturing, also called fracking—a somewhat controversial practice because of its negative environmental impact—is a process of pumping water, sand and other proppants at tremendously high pressure into underground oil and gas reserves in order to break apart the surrounding rocks through which natural gas and petroleum could flow more freely and thereby be extracted more easily. Instead of pumping water, scientists from the Atomic Energy Commission predicted that nuclear explosives would create more and bigger fractures and hollow out a huge cavity that will serve as a reservoir for the natural gas released from the fractures, facilitating much smoother extraction.

Related: How The Soviets Put Out Oil Well Fires by Using Nuclear Bombs

And thus in 1967, the Atomic Energy Commission teamed up with officials from the U.S. Bureau of Mines and El Paso Natural Gas Company for a series of underground experiments to determine if nuclear explosions could be useful in fracturing rock formations for natural gas extraction. A remote site, 21 miles southwest of Dulce, New Mexico and 54 miles east of Farmington was chosen because of its natural gas deposits that were known to be held in sandstone. A 29-kiloton device named Gasbuggy was lowered to a depth of 4,227 feet (about 1.2 km), and then the well was backfilled before the device was detonated. There was no mushroom cloud, but the ground shook spectacularly beneath the feet of a crowd that had gathered to watch the detonation from atop a nearby butte.

Scientists lowers a 13-foot by 18-inch diameter nuclear device codenamed “Gasbuggy” into a New Mexico gas well. Photo: U.S. Department of Energy

The underground detonation vaporized the rocks to create a molten glass-lined cavern about 160 feet in diameter and 333 feet tall. Unfortunately, the cavern didn’t survive as predicted. Under the tremendous pressure from the surrounding rocks, the cavern collapsed after only a few seconds. However, the explosion had fractured rocks more than 200 feet in all directions, and significantly increased natural gas production.

Project Gasbuggy was merely a proof-of-concept. There were no attempt to extract the natural gas released. That was to come later, and was one of the main objectives of the subsequent experiment called Project Rulison.

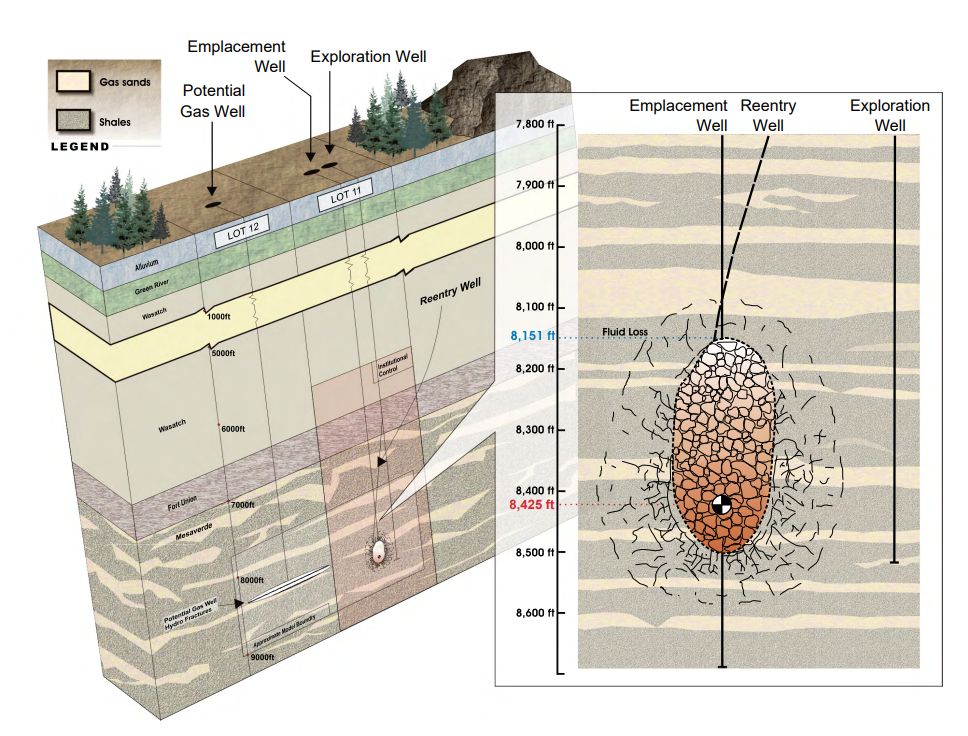

Project Rulison took place in the rural community of Rulison, Colorado. On September 10, 1969, the Atomic Energy Commission along with the Austral Oil Company of Houston, Texas, and the nuclear engineering firm CER Geonuclear Corporation teamed up and detonated a nuclear device at a depth of approximately 8,400 feet (2,600 meters). The detonation produced extremely high temperatures that vaporized a volume of rock, creating a somewhat spherical cavity. The fractured rock above the roof of the cavity collapsed shortly after the detonation, forming a rubble-filled chimney. An exploration well drilled into this cavity found a high concentration of natural gas, as predicted. However, the gas was too radioactive to be used for commercial purpose, and applications such as cooking and heating homes. The oil well was abandoned as a result.

Project Rulison. Image by U.S. Department of Energy

Before the button to Project Rulison was pushed, activists and environmentalists tried to prevent the detonation by storming the site and hiking into the blast exclusion zone. But that didn’t stop them. With protesters still hollering merely 2 miles from the blast zone, the AEC went ahead with the blast.

“We were lifted six to eight inches in the air when the shockwave hit us,” remembers Chester McQueary. “This was to be a test, but they said openly at the time that if it was successful then they planned in the 20 mile stretch between the towns of Rifle and Parachute they would set off between 100 or 200 of these nuclear blasts to fully develop the gas field.”

Despite the radioactivity, Project Rulison was deemed a success giving federal scientists enough confidence to go ahead with the third and final experiment —Project Rio Blanco.

Project Rio Blanco took place on May 17, 1973 in Rio Blanco County, Colorado. Three 33-kiloton nuclear devices were detonated nearly simultaneously in a single emplacement well at depths of 5,838, 6,230, and 6,689 feet (1,779, 1,899, and 2,039 m) below ground level. If it had been successful, plans called for the use of hundreds of specialized nuclear explosives in the western Rockies gas fields. The previous two tests had indicated that the produced natural gas would be too radioactive for safe use, and the Rio Blanco test found that the three blast cavities had not connected as hoped, and the resulting gas still contained unacceptable levels of radionuclides.

By 1974, approximately $82 million had been invested in the nuclear gas stimulation technology program. It was estimated that even after 25 years of production of all the natural gas deemed recoverable, only 15 to 40 percent of the investment would be recouped. Also, the fear that stove burners might emit trace amounts of blast radionuclides into family homes did not sit well with the general public. The contaminated gas was never channeled into commercial supply lines.

Project Rio Blanco would proved to be the final Plowshare experiment. Under mounting public opposition, Project Plowshare was discontinued in 1975. Shortly after, the Treaty on Underground Nuclear Explosives for Peaceful Purposes was signed by the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

All three sites now remain under the watch of the Department of Energy’s Office of Legacy Management which looks after clean-up operation. All three sites are now marked with stone markers.

Project Rulison Test Site. Photo: Bronco925/Wikimedia

Project Rio Blanco test site. Photo: Bronco925/Wikimedia

Project Gasbuggy placard. Photo: Chubbles/Wikimedia

Comments

Post a Comment