A species disappears from our planet about every 30 minutes. From climate crises to man’s carelessness, there are endless factors that drive the living into a black hole of non-existence. Till date, the most extraordinary of these eliminations occurred in a family of tiny insects—the Rocky Mountain locusts which became in 1902 the only agricultural pests to face complete extinction. But this notorious species has continued to swarm the minds of farmers and entomologists long after their mysterious disappearance, and for good reason. In 1875, Plattsmouth, Nebraska witnessed the largest swarm of these Rocky Mountain locusts that shook the world with its scale. The swarm exceeded in reputation even the desert locust swarm of Africa, cementing its reputation in history for centuries to come.

A specimen of the Rocky Mountain locust. Photo: Janique Goff/Flickr

Vagabonds with Wings

Historians and entomologists have gathered stringent data about the 1875 Rocky Mountain locust plague from the first-hand account of A.L. Child, transcribed by Riley et al. According to his sightings, the swarm was unprecedented in its size—a staggering 1,800 miles long and at least 110 miles wide. It hovered over Nebraska for five days over areas that were equal to Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Vermont. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, the swarm consisted of some 12.5 trillion insects. It was possibly the largest grouping of animals ever. The disaster caused the already fed up farmers to give up their killing tactics and let the insects feast on their fields and homes. Laura Ingalls Wilder later penned a fictionalised account of the havoc that was wreaked in the 70s in her 1937 novel On the Banks of Plum Creek.

For years before the event, locusts had pierced through agricultural lands like vagabonds hungry for wanton destruction. Billions, possibly trillions of shimmering fliers pervaded the North American skies, blanketing farm fields and house backyards every year. They spared nothing—feeding on rye and barley, wheat and fruits was a given, but even the laundry hanging on ropes and the blankets covering the lawns were delicacies on the table. Children would cringe at the aviators clinging to their trousers, and stomp as many as they could under their feet. Farmers took the fields with guns and rifles, aiming to kill along with setting fires in patches to burn the insects alive.

An image of a Rocky Mountain locust on a ceramic urn by Julia Galloway. Photo: Harvard Arts/Flickr

The species has been commonly identified as a kind of grasshopper that flies in large swarms. But in reality, these locusts were vastly different from grasshoppers, with short stout legs and a glistening brown body as opposed to the leafy green. Contrary to the whimsical cricketing of hoppers that fills the late hours of night by the field, the sound of a locust was almost absent, evident only in their biting and chewing. This species was purely American, and inhabited no other lands. They swarmed over the fertile river valleys of the West on both sides of the Rockies, which was their feeding ground and sadly, the site of their destruction as it later turned out.

Unlike other hoppers and crawlers, the Rocky Mountain locusts vanished off the face of the earth as quickly as they used to take over land in life. Their sheer size went to zero a mere 28 years after the horrific swarm of 1875. Entomologist Jeffrey A. Lockwood explains that this happened due to a number of plausible reasons that mainly relate to inadvertent destruction by man’s actions. In their “Permanent breeding zones” of the West, the female locusts used to lay thousands of eggs in the ground. Finding it to be highly fertile, the farmers took these fields with horse-driven instruments and began ploughing. As the soil turned, hosts of eggs were continually destroyed. While the locusts seemed impervious to the rifles and fires, their numbers entered a gradual decline as men also brought in insect-eating birds and environment-altering plants for their farming.

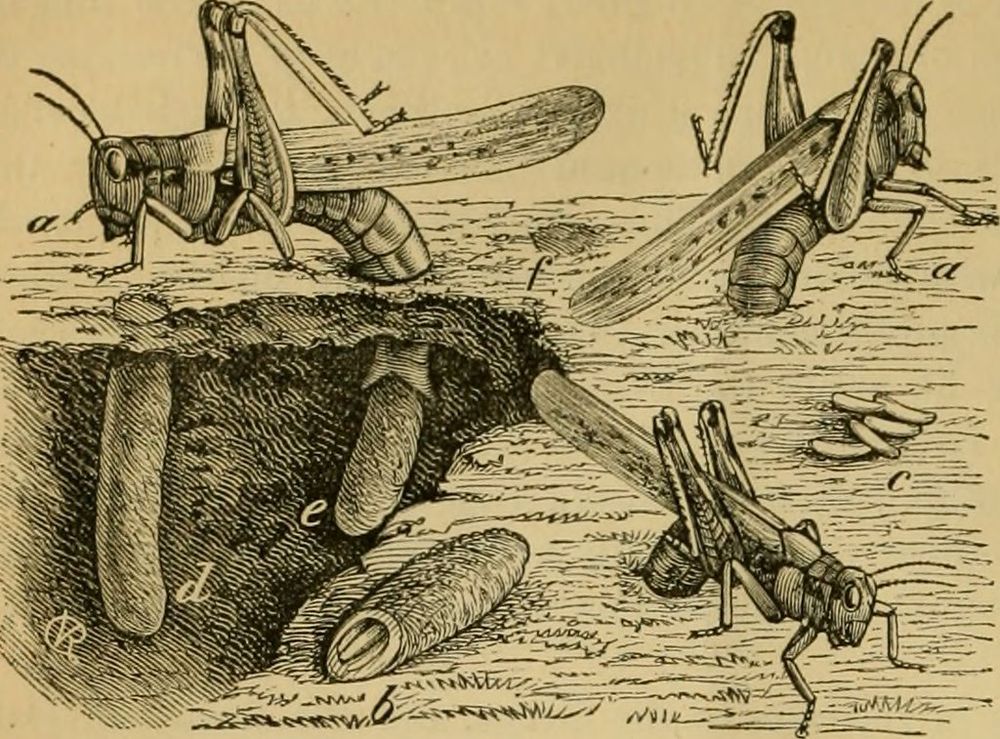

Illustration of egg-laying by females (1869).

The last time we witnessed a living locust was in 1902. Naturally, the large and unpleasant existence meant that the tiny creatures were taken for granted. Everyone was wishing for their extinction and no one bothered to collect samples. This is why even today, some 120 years later, the largest collection of locust fossils we have is of 100 locusts only, which sits in the Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia. This has caused a major deterrence in further studies that could determine other causes behind the mass extinction of the pests.

Dr Lockwood has suggested that the largest natural reservoir of these locusts exists in the frozen glaciers of the Rocky Mountains. His expedition had revealed lumps of broken wings and tangled legs. Excavations confirmed them to be 800-year-old. While their complete absence today makes it hard for one to picture their existence, analyses have confirmed that the locusts were in fact a real species distinct from other hoppers. Etymologists have officially named them as Caloptenus Spretus. Spretus means ‘despised’ and suits the reputation of the insects more than perfectly. The specimens have hence proved invaluable in the classification of the pests. In the search for larger deposits of these dead species, Dr Lockwood floats a dreamy possibility that maybe, somewhere on earth, an untouched pocket of the pests continues to exist in hiding. Theorists have confirmed that the resurfacing of the locusts is possible and plausible, but until then, only the memory of their wrathful swarms continue to keep us company.

References

# New York Times

# Locust by Jeffrey A. Lockwood

# Cornell Chronicle

# The Rocky Mountain Locust by C.V. Riley

If these were such a destructive element why is their extinction a bad thing? The won't be destroying the food supply any longer.

ReplyDeleteBecause that’s exactly what another species might say about us

Delete