On December 2, 1943, the Germans launched a surprise attack on a key Allied port in Bari, Italy, sinking more than 20 Allied merchant ships and killing more than 1,000 American and British servicemen and hundreds of civilians. Among the ships sunk was the SS John Harvey, an American Liberty ship carrying a secret cargo of mustard gas bombs. The deadly attack, which came to be dubbed as “the Little Pearl Harbor”, released a toxic cloud of sulphur mustard vapor over the city and liquid mustard into the water, prompting an Allied coverup of the chemical weapons disaster. But it also led to an army doctor’s serendipitous discovery of a new treatment for cancer.

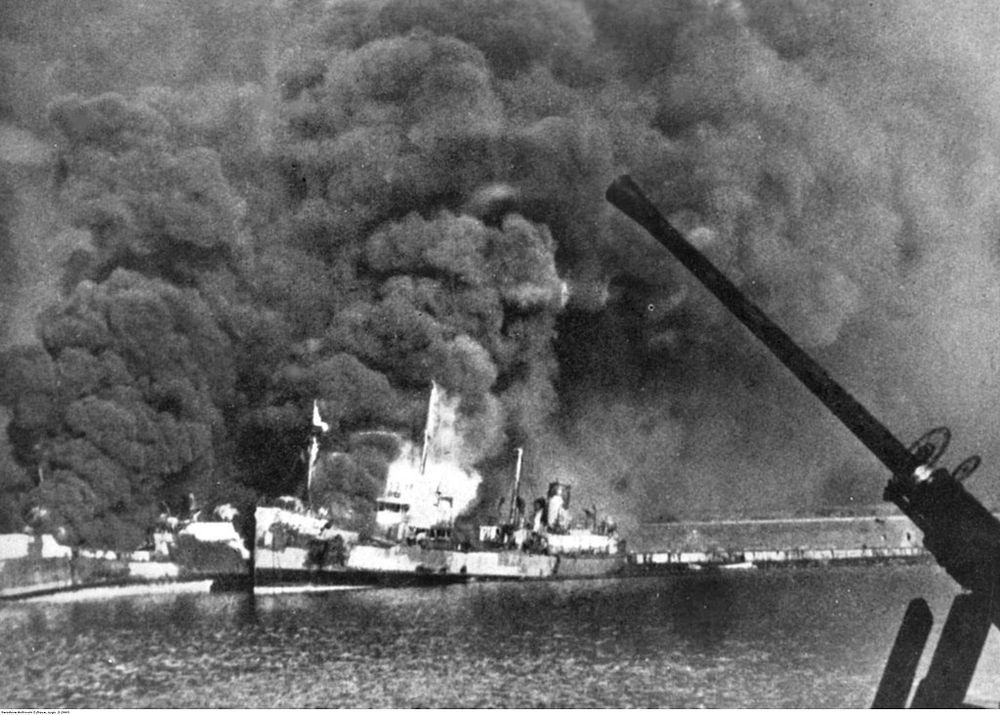

Allied ships burn during the German attack on Bari.

Mustard gas was used extensively by the Germans during the First World War. It was a feared weapon that caused sever skin oedema and ulceration, blindness, suffocation and vomiting. Mustard gas caused internal and external bleeding and attacked the bronchial tubes, stripping off the mucous membrane. This was extremely painful. Fatally injured victims sometimes took four or five weeks to die of mustard gas exposure. The use of this gas and other chemical weapons in war was banned by the Geneva Protocol of 1925. However, there was no ban on their manufacture or transport. The Allies were concerned that the Germans might use chemical weapons in World War II and wanted to be in a position to retaliate if such weapons were used against them. So in August 1943, President Roosevelt approved the shipment of chemical munitions containing mustard agent to the Mediterranean theater. Two thousand mustard gas bombs were loaded onto the USS John Harvey, and the ship, commanded by Captain Elwin F. Knowles, set sail from Oran, Algeria, to Italy, on 18 November 1943. On 26 November, the John Harvey sailed through the Strait of Otranto to arrive at Bari.

The port of Bari was crammed with ship from stern to bow, and the John Harvey had to spend several days waiting for its turn to unload. Captain Knowles wanted to tell the British port commander about his deadly cargo and request it be unloaded as soon as possible, but the presence of the gas bombs was highly classified and the captain was forbidden from divulging its existence to the British port authorities.

On December 2, 1943, the Germans launched a surprise attack. More than one hundred Junkers Ju 88 bombers swooped over the overcrowded harbor indiscriminately bombing and destroying the waiting ships. John Harvey was struck and destroyed in a huge explosion. It’s deadly cargo of liquid mustard spilled into the water mixing with oil from the sunken ships. Some mustard evaporated and mingled with the clouds of smoke and flame. Nearly all crewmen of John Harvey who knew what was in the hold perished in the sinking, so rescuers dealing with the casualties had no idea what they were up against. Many who made it to the hospital were greeted with a warm blanket that was wrapped around their poison-soaked clothing, sealing their fate as they awaited care. By next morning the nurses were surprised to find the wards full of swollen, blistered patients, temporarily blinded. The doctors suspected some form of chemical irritant but were unsure what it was.

Unidentified Canadian soldier with burns caused by mustard gas in 1917.

Then suddenly, patients who were in relatively good condition started dying. These mysterious deaths left the doctors baffled. At first it was suspected that the Germans had dropped chemical bombs, and Bari was put on red alert. The Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ) in Algiers sent for Lieutenant Colonel Stewart Francis Alexander, a young chemical warfare specialist, to the scene of the disaster.

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander immediately recognized the symptoms as the result of mustard gas poisoning. He traced the epicenter to John Harvey, and confirmed mustard gas as the responsible agent when divers located a fragment of the casing of a M47A1 bomb. But the Allied High Command suppressed news of the presence of mustard gas, in case the Germans believed that the Allies were preparing to use chemical weapons, fearing it might provoke them into pre-emptive use. Alexander’s report was immediately classified, and all mention of mustard gas was stricken from the official record. The deaths were attributed to simply “burns due to enemy action.” However, the presence of multiple witnesses forced the United States to eventually admit the presence of the chemical.

In all there were 628 known casualties, including 86 deaths, but there were probably many more. The cloud of vaporized mustard gas had drifted across the town affecting and killing many more civilians. These deaths were never recorded.

In the midst of the disaster, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander made an interesting discovery. While studying tissue samples of autopsied victims, Alexander discovered that mustard gas kills white blood cells. White blood cells, among other things, are capable of rapidly dividing, which prompted Alexander to wonder whether it might also be useful in killing rapidly dividing cancer cells, as well.

Modern chemotherapy drugs. Photo: Wikimedia

The effect of mustard gas on bone marrow and white blood cells had been known since the First World War. A preliminary research conducted in 1935 showed that mustard gas inhibits growth of tumors in mice. With the advent of World War 2, research on chemical weapons resumed, and the newer knowledge and techniques of a quarter of a century of scientific progress was utilized. After the U.S. entry into the Second World War, the Office of Scientific Research and Development initiated research on mustard gas and commissioned two universities—Yale University and the University of Chicago—to make further studies. In 1942, Louis Goodman and Alfred Gilman of Yale University made the first clinical trial on human patients suffering from advanced lymphomas. Their improvement, although temporary, was remarkable. The University of Chicago conducted similar clinical trials using a different agent. But wartime secrecy prevented any of this ground-breaking work on chemotherapy from being published. Once wartime secrecy ended, papers were released and experiences from both scientific research and the disaster at Bari converged and led researchers to look for other substances that might have similar effects against cancer. Eventually, the first chemotherapy drug named Chlormethine was developed. Since then, many other drugs have been developed to treat cancer, usually less toxic and more targeted in their effects. So what began as a weapon aimed to destroy human life, is now a successful promoter of life thanks to the pivotal work of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander, Louis Goodman, Alfred Gilman, his colleagues, and their successors.

Certainly a disaster, but I must wonder, did the Allies learn nothing from

ReplyDeletePearl Harbor?