If you visit the Darwin Archive at Cambridge University Library (DAR 191) today, you will find notes on orangutans recorded by Charles Darwin that are labelled as “man” and not “orangutans”. These were notes compiled during careful observations of the species in the months of 1838, within the tamed confines of the Zoological Gardens of England. One of them, dressed in human clothes and drinking tea between her fits of passion, was Jenny. Darwin;s observations of the animal went on to shape the concept of evolution as we know it, and opened doors to the possibilities of new lineages of mankind. But it took the famed evolutionist over two decades to reveal these findings to the world. Why?

Photo: jplenio / 977 images

By the 1800’s, similarities had already been drawn between the common man and apes and bonobos, but the orangutan was still a bizarre species to be compared to humans. In the early 1600s, Dutch physician Jacobus Bontius from the island of Java had written of wild apes around him, calling them “Ourang Outang”, meaning man of the forest. The name had stuck, and was used in the widely known parallel drawn by French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck: he proposed a direct line of descent from orangutans to humans in his Philosophie Zoologique (1809). Technically, Lamarck and many of his contemporaries referred to all such animals as “Ourang Outang” (thanks to Bontius), so while his revelations were in fact referring to apes, the scandalous allusion that man had evolved from orangutans garnered widespread criticism. Geologist Charles Lyell in his Principles of Geology (1830-1833) outrightly rejected the idea, and discredited the concept of evolution on the grounds of its absurdity.

Orangs Among Humans

Orangutans originally come only from the islands of Sumatra and Borneo in Southeast Asia. But the very year that Lyell’s book came out, the Zoological Garden in London’s Regent’s Park welcomed its first living, breathing orangutan. While he survived for no more than three days, he was followed by one in 1838 named Lady Jane, shortened to Jenny; a male called Tommy; and another later who was also named Jenny. The last of them was visited by Queen Victoria herself, and who would have thought so, but was described as “frightful & painfully and disagreeably human” by the regent.

But let’s backtrack a little. Just as the first Jenny arrived in London in 1838, so did Charles Darwin from his voyage on board the Beagle. His theory on transmutation or evolution was still at its nascent stage, and in its development he was free and eager to visit the zoo and experiment with animals. On a fine summer afternoon in March ambled out of the Giraffe House at the London Zoo, and saw Jenny the orangutan being teased by her keeper. In a daring move that would go down in history as not only revolutionary but also theatrical, Darwin climbed into the cage with the orangutan in it. “I saw also the Ourang-outang in great perfection: the keeper showed her an apple, but would not give it to her, whereupon she threw herself on her back, kicked & cried, precisely like a naughty child,” he wrote later in a letter to his sister, Susan.

Portrait of Jenny. Printed by W. Clerk, London, 1837.

For a man speculating about evolution from every angle, even the slightest similarity of an animal to a human sparked intrigue. In the months that followed, Darwin started maintaining extensive notes observing Jenny, and even her pal Tommy, contemplating questions of descent. Did she feel the same way a human felt? Did she understand fairness and foul play? Could she grasp right from wrong?

His notes, discerned and analysed by historians of science John van Wyhe and Kjaergaard, revealed many connections between men and orangutans. For one, the latter understood the appeal of sex and preferred sight over smell to identify a female. Jealousy was another prominent emotion: when Jenny became annoyed at not being let out of her cage, she “shook the cage & knocked her head against door because she could not get out. –Jealous of attention to other.” Tommy, was no less. Darwin would find the both of them obsessing over mirrors, kissing them, rubbing against them, making faces at it. Self awareness, as in humans, was high in the orangutans, and Darwin was convinced they shared ancestors with humans.

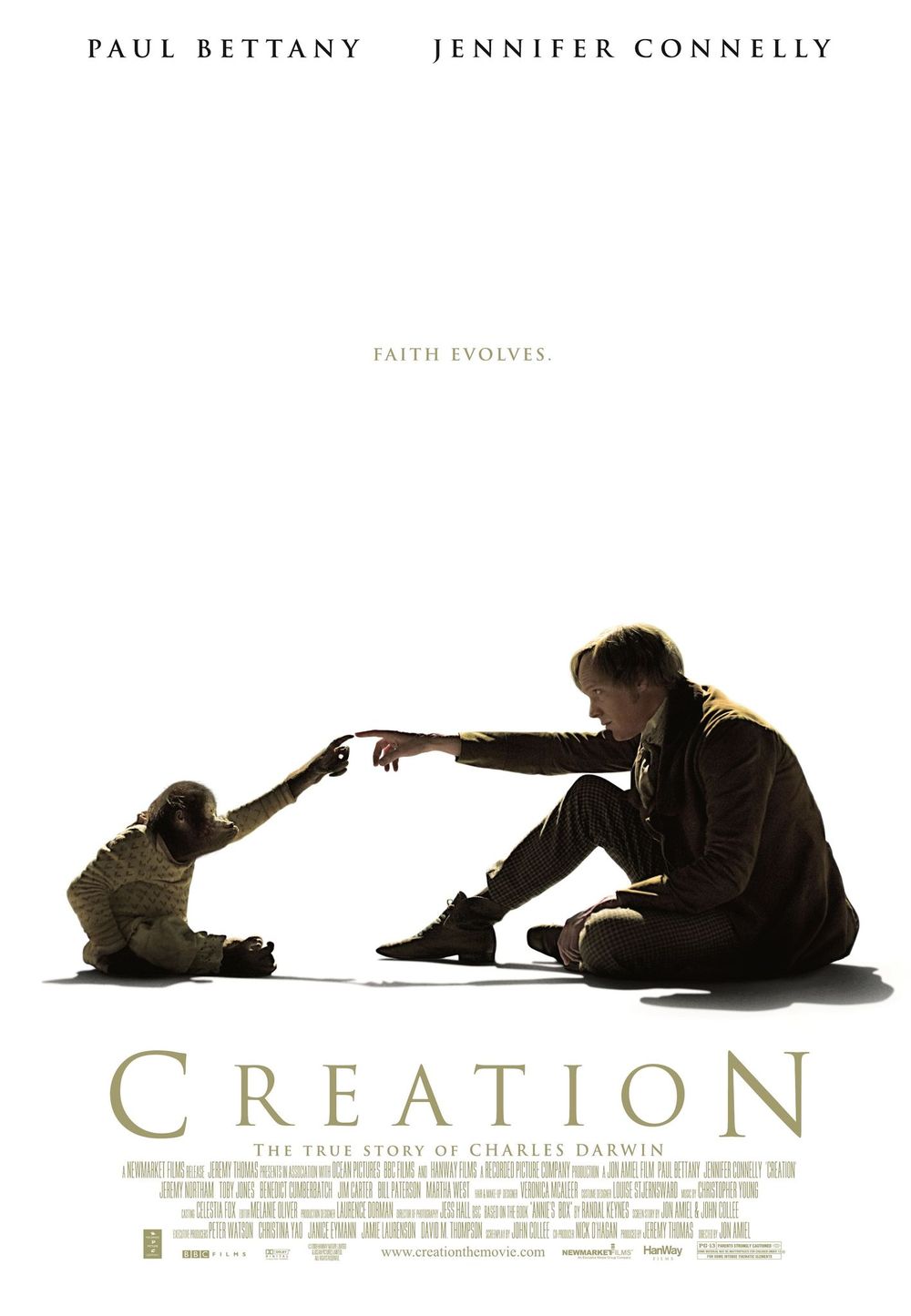

In 2009, the iconic image of Charles Darwin high-fiving an orangutan in a cage was immortalised in a Hollywood movie called Creation. But his association with the species went way beyond that momentary exposure. For months he studied the orangutans closely, feeding them, watching them, interacting with them in the controlled environment of the zoo. As he watched her daily, Jenny “...covered herself up with two pocket handkerchiefs just like girl with shawl spread them out—considered them as her property would not give them up to me. but the keeper brought them & gave them. followed me & bit me for having taken it away & tried to pick my pocket.”

After meeting Jenny the orangutan, Darwin waited almost 21 years to publish his findings in his book, called Origin. While some have attributed the decades to a fear of backlash from the Church of England, van Whye suggests that he took the time to publish fourteen works that lay grounds for the scandalous claim he was preparing to make.

Eventually, Darwin’s theories were accepted even by the carpers. By 1859 even Lyell had turned, acknowledging not only the existence of evolution but terming its complete acceptance as to “go the whole orang.” What this means is that humans are not, and have never been, separate from the rest of the animal kingdom. To study evolution then, means not only to study humans like animals, but to see them as animals themselves.

References

# Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences

# National Geographic

# Forbes

Comments

Post a Comment