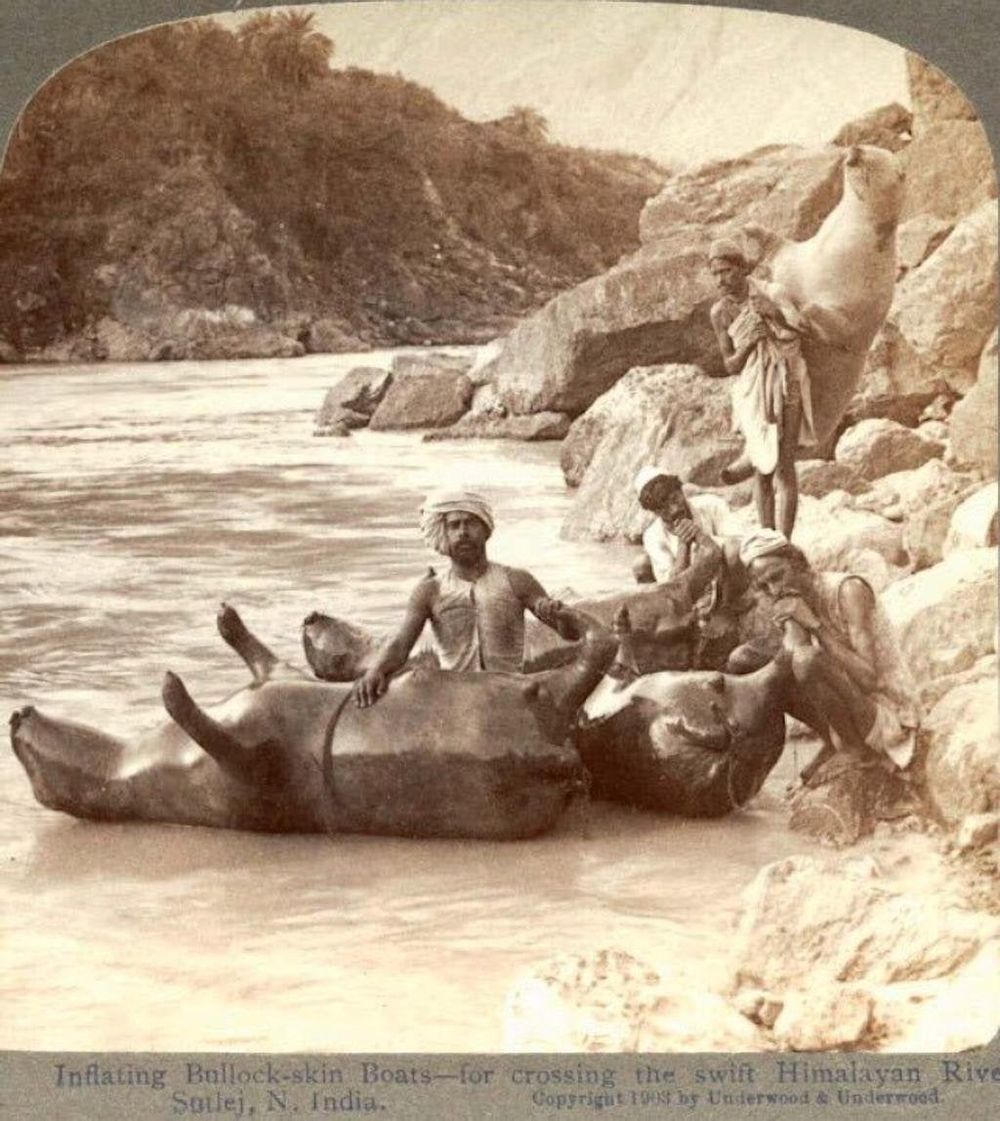

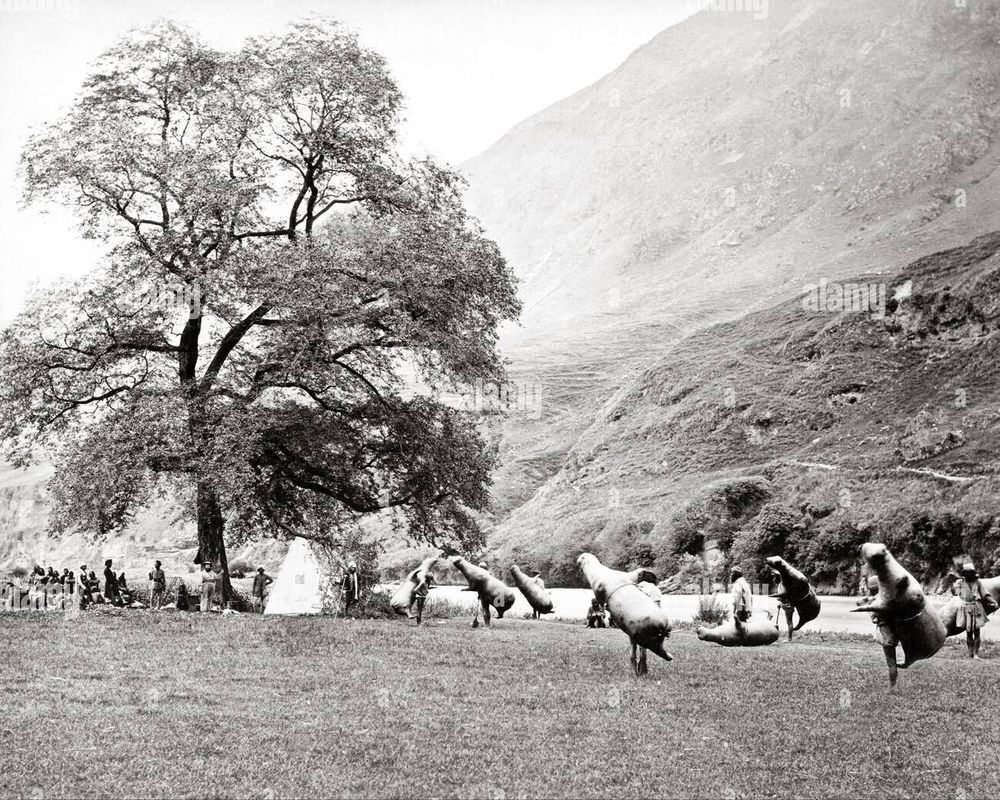

In the early 1900s, American school teacher, traveler, and photographer, James Ricalton, went to India and traveled extensively throughout the subcontinent, documenting and recording the lives, culture and customs of the natives through photography. Once, while visiting some remote villages in the hills of Punjab in the lower Himalayas, he came across an unusual sight, which he captured in his stereoscopic camera. Only the left hand side of the image is reproduced here below.

Ricalton describes the scene:

This is some twenty miles from Naldera, up in the hill country of the Punjab. The mountain river here is deep and swift; you can see ahead how high, steep banks wall it in and you can judge how pouring rains, draining from such slopes, would turn this stream into a fiercely raging torrent.

These men are natives in their customary clothes, and the rather ghastly looking objects with which they are busy are the hides of cattle, sewed up tightly and inflated with air till they can be used like enormous life-preservers. Two of the men you notice, are still at work blowing their “boats” full of air; they have cords there all ready to tie up the end of the skin when it is sufficiently distended.

Another has done the blowing-up at home and is bringing his skin down over the rocky bank; it is bulky but naturally very light and comparatively easy to handle.

When they are ready to start each man will throw himself across one of the inflated skins, using his foot on one side and a short paddle on the other side to propel the queer craft. If his balance is not perfect of course the craft rolls over and he gets a ducking, but practice makes skilful, and, as a matter of fact, small loads of freight and even passengers are ferried across in safety. If several passengers are to be taken over, it is customary for two “boats” to start out side by side, the passengers on the different floats taking hold of each other to help balance the queer craft.

—India Through the Stereoscope: A Journey Through Hindustan

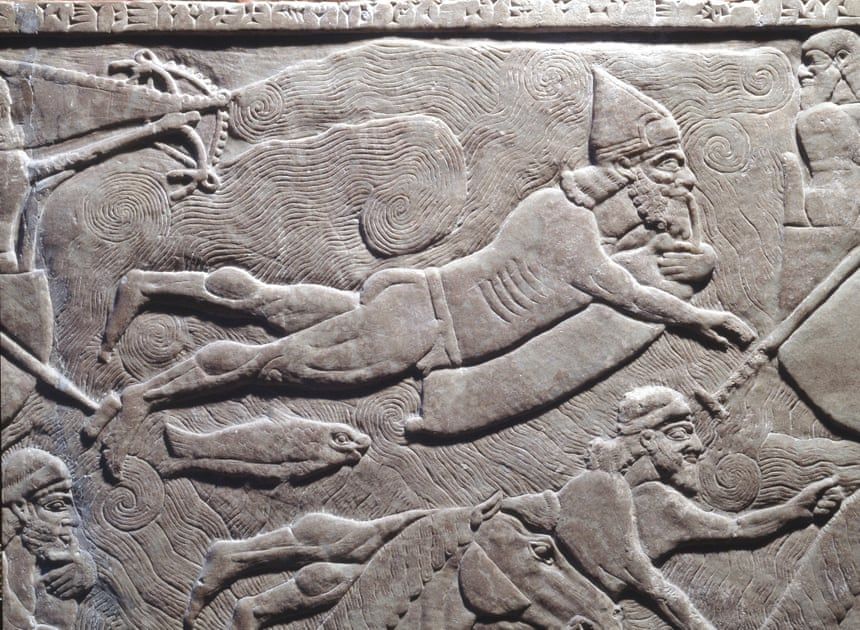

This primitive technique of crossing rivers and streams is neither unique to India nor invented by these natives. One of the oldest examples of this technique can be found in a bas-relief from ancient Mesopotamia, from Nimrud where it once decorated the palaces of King Ashurnasirpal II, who ruled Assyria from 883 to 859 BC. Now at the British Museum, the relief shows Assyrians soldiers swimming supported by small inflated skins, probably of goats. Cyrus the Great also used inflated or stuffed animal skins to cross a Babylonian river as mentioned by Xenophon. Another example is Darius I who used the same technique in 522 BC to cross the Tigris River. The Mongol troops of Genghis Khan carried inflatable animal skins with them on their westward conquests. His grandson Kublai Khan also used inflated skin along with wooden rafts when the occasion required. Much later, the Romans and the Arabs still resorted to this simple but ingenious solution for the same purpose.

An Assyrian soldier floating on a goat-skin float.

In order to prepare the hide to be used as a floatation device, the goat or buffalo was flayed differently for the skin was needed intact. William Moorcroft who travelled extensively throughout the Himalayas, Tibet and Central Asia, described the method as he saw being employed in Punjab in 1820, which is recounted by James Hornell in The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland published in 1942.

The skin having been cut through around each knee, a long incision is made in the back part of a hind leg, extending down to the knee; through this the skin is gradually flayed off. When detached the skin is doubled up and buried for a few days, to allow decomposition to proceed sufficiently for the hair to be rubbed off by hand or with a blunt wooden knife. Turned inside out, the natural openings (mouth, eyes etc.) are then stitched up. Finally it is turned back again and the main incision sewed up with thongs of raw hide. The open end of three legs are now tied up, the fourth being left open to serve as a tube for inflating the skin. Thin tar from deodar or other pine is then poured into the skin and shaken about until the interior surface is thoroughly impregnated with it. The exterior in turn is tanned by steeping in an infusion of pomegranate husks.

When inflated a bullock’s skin looks absurdly like a huge hairless bear. A dog not used to the sight will often growl and show signs of uneasiness. Equally strange is the sight of a man carrying on his back what appears to be an animal three or four times his own weight and bulk.

...

The skins are kept dry when not in frequent use; when wanted again they require a preliminary soaking in water in order to render them sufficiently soft and supple to be blown out. Usually a reed tube is inserted into the leg opening for the inflator to blow through.

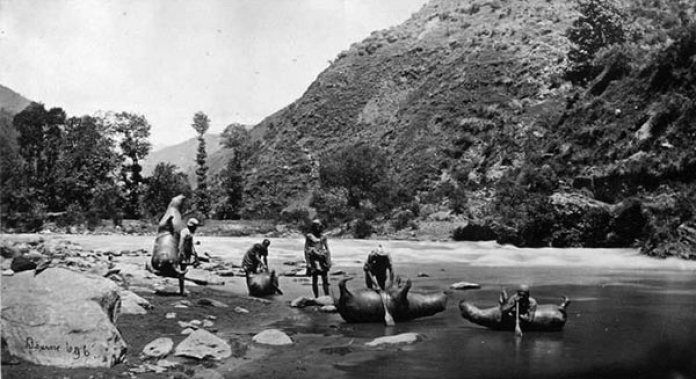

Before the construction of bridges and the availability of better boats, floats were indispensable for crossing unfordable mountain rivers in India. In spite of its apparent primitivity and crudeness, these floats worked wonderfully. Moorcroft tells how on one occasion his whole party, consisting of about 300 persons, 16 horses and mules, and about 200 maunds (a unit of weight in used in India equivalent to about 37 kg) of merchandise and baggage, were ferried across the Sutlej by 31 watermen, each managing one skin, within an hour and a half.

Inflated bullock skins for ferry boats on Sutlej River in the Punjab, India. Photo: Digital Commonwealth

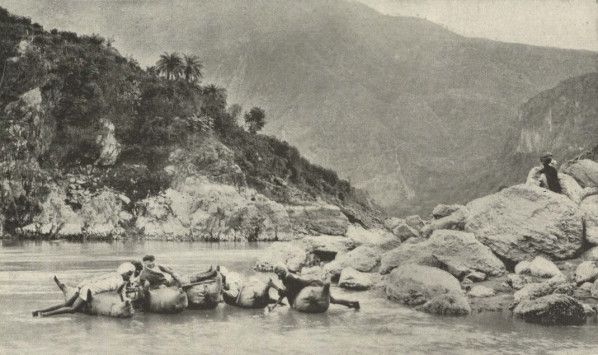

Crossing the Sutlej near Shimla upon inflated animal skins. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Locals use bullock skins to cross a river in Kashmir.

Cow or ox skin raft loaded with wool in China. Photo: Arthur de Carle Sowerby (1885-1954)

Locals carry inflated animal skins for river crossing, India, circa 1860. Photo: Samuel Bourne

Sadlermiut man paddling an inflated walrus or seal skin, drawn by George Lyon c. 1830.

Comments

Post a Comment