When the advancing Third Army of the United States marched into the captured German town of Merkers-Kieselbach towards the end of World War 2, they received a tipoff from two women that a disused salt mine near Merkers contained gold stored by the Germans, along with other treasures. The piece of information was quickly relayed to the higher command and the story was soon confirmed and collaborated by other witnesses. Later that month, Generals Eisenhower and Patton themselves traveled to the mine to inspect the hundreds of tons of gold and precious artwork that the Nazi had hidden away in underground chambers.

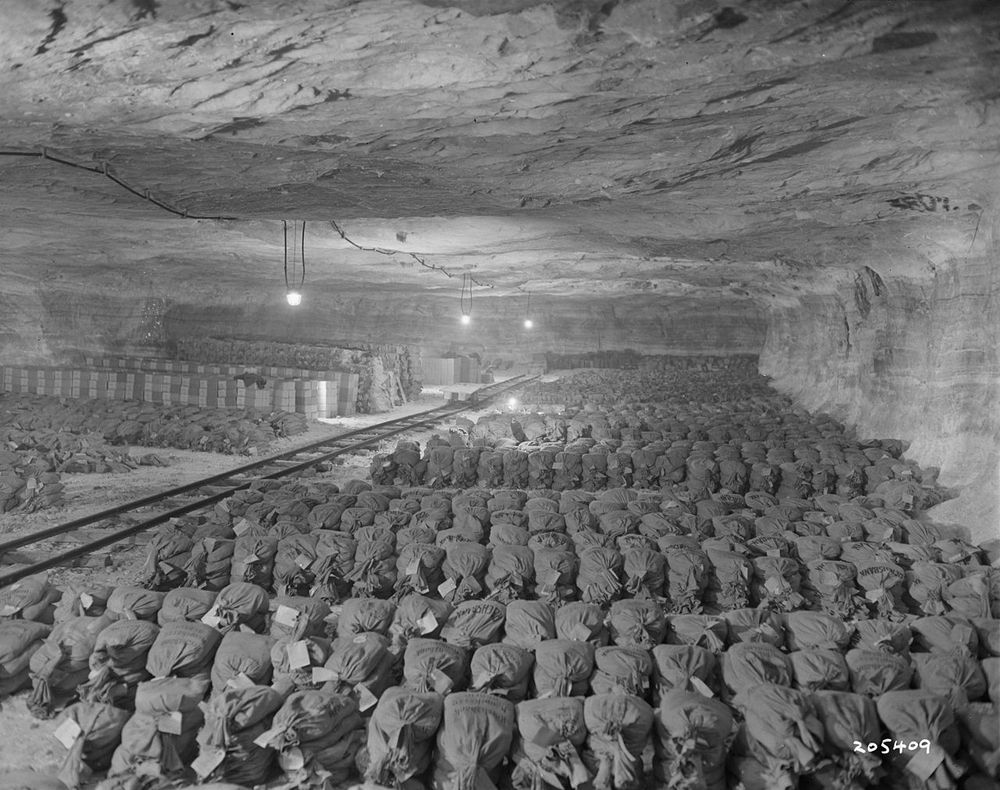

Nazi treasure at Merkers mine.

During their decade-long rule, the Nazis looted hundreds of millions of dollars worth of gold from many central banks of Europe. Much of it was spent in purchasing war goods from neutral countries, but they still had a considerable quantity. The bulk of this gold reserves was held at the Reichsbank in Berlin. But when the Allies began to push towards the city in early 1945, a large quantity of this gold was dispersed to numerous branches of the Reichsbank in central and southern Germany.

In February of 1945, the Reichsbank in Berlin was hit by Allied bombing that nearly destroyed the bank, including its presses for printing currency. Immediately after, it was decided to send most of the gold reserves, worth some $238 million, and a large quantity of the monetary reserves to a mine at Merkers, about two hundred miles southwest of Berlin, for safekeeping. A large number of salt and potassium mines in Germany were already requisitioned by the government for the manufacture and storage of weapons and ammunition, as over ground factories were targeted by Allied bombing.

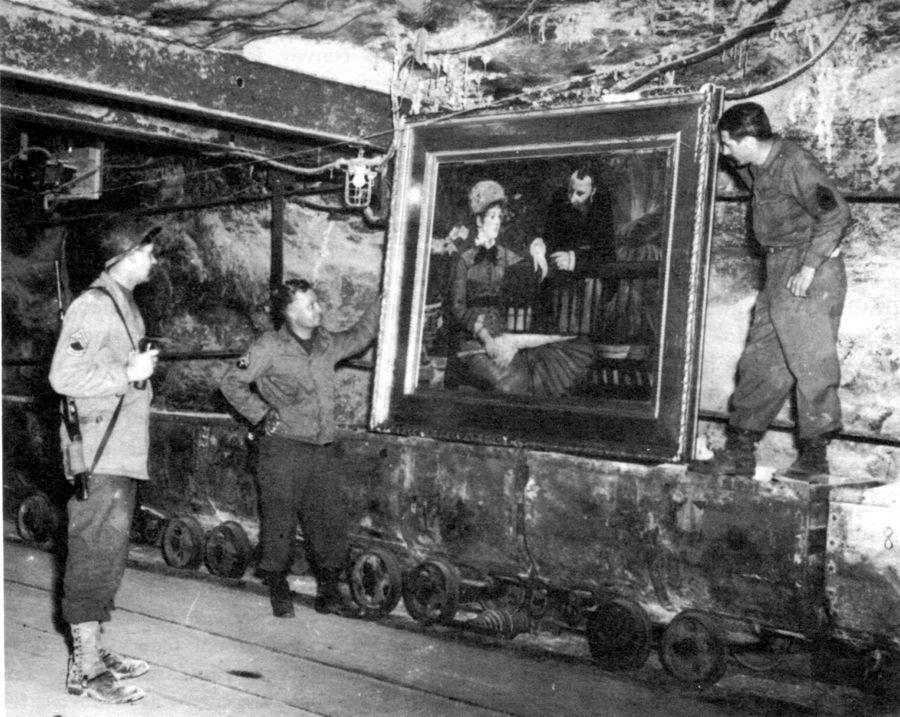

Hardly a week after American B-17 bombers of the Eighth Air Force dropped nearly twenty-three hundred tons of bombs on Berlin, a shipment was readied to the be transferred to Merkers by rail. It contained a billion Reichsmarks bundled in one thousand bags, and a considerable quantity of foreign currency. Once the train reached Merkers, the treasure was unloaded and placed in a special vault area in the mine. Throughout the rest of February and March, until the fall of Berlin, shipments continued to arrived at Merkers with Nazi loot. These included gold and silver jewelries confiscated from Jews, ranging from dental work to cigarette cases, diamonds, gold and silver coins, foreign currencies, and gold and silver bars. The Reichminister for Education also sent the nation's art treasures to the mines for safekeeping. These included one-fourth of the major holdings of fourteen of the principal Prussian state museums.

General Eisenhower inspects stolen artwork at Merkers mine.

As the Third Army moved toward Merkers, the Reichsbank officials made a frantic effort to remove as much gold as possible, as well as other valuables, from the mines and sent it to different destination. But the speed of the American advance and the partial shutdown of the Germany railway system due to the Easter holidays hampered their effort. Bank officials soon realized that total recovery of the treasure was impossible and decided to concentrate on Reichsmarks instead because they were in short supply in some parts of Germany. On April 2, Reichsbank officials loaded about 200 million Reichsmarks and some fifty packages of foreign currency unto a truck and drove off destined for Magdeburg and Halle. Workers also loaded one railway car with currency but the bridge over which the train was to pass was blown up by approaching American troops, and the currency had to be moved back to Merkers.

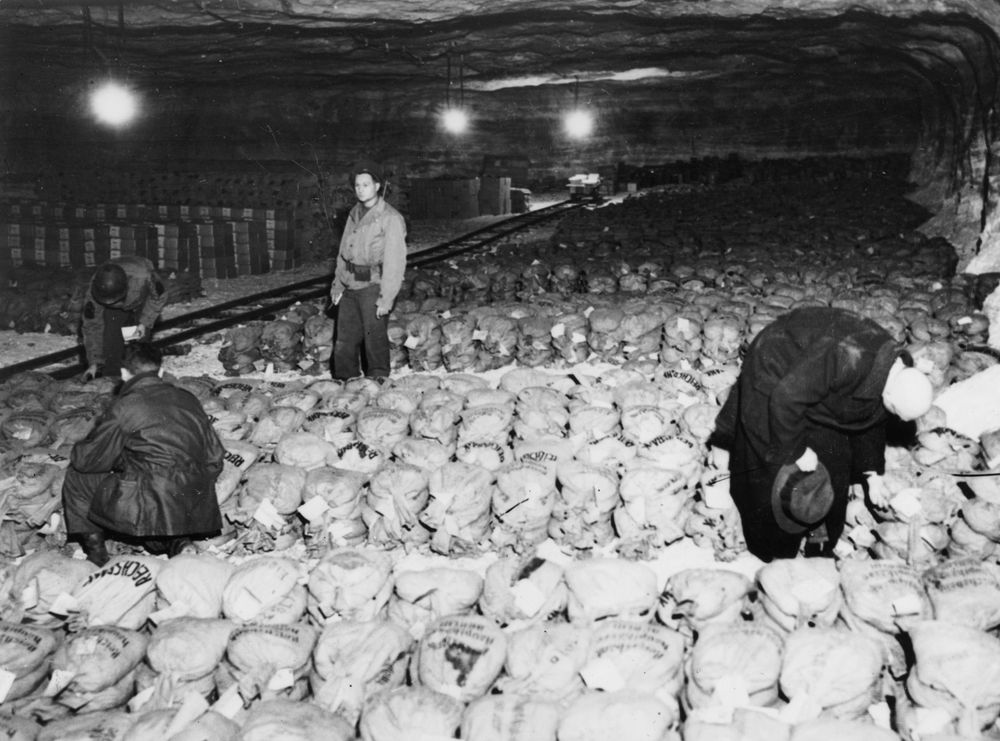

Less than a week later, American troops walked into Merkers. Once they learnt about the mines and the treasure it contained, they placed guards on the mine’s five entrances. On April 7, Lt. Col. William A. Russell the Ninetieth Infantry Division's G-5 officer, along with other officers and Signal Corps photographers, entered the mine. They took the elevator to the bottom of the main shaft twenty-one hundred feet beneath the surface. In the main haulage way, stacked against the walls, they found 550 bags of Reichsmarks. But the real treasure was in the vaults blocked by a brick wall three feet thick. In the center of the wall was a large bank-type steel safe door, complete with combination lock and timing mechanism with a heavy steel door set in the middle of it. The brick wall was blasted through with a half a stick of dynamite.

The vault was approximately 75 feet wide by 150 feet long with a 12-foot-high ceiling. Inside the vault was more than seven thousand bags of gold bars and coins, 55 boxes of crated gold bullion, hundreds of bags of gold items, over 1,300 bags of gold Reichsmarks, British gold pounds, and French gold francs, 711 bags of American twenty-dollar gold pieces, hundreds of bags of gold and silver coins, hundreds of bags of foreign currency, more than two thousand bags and 1,300 boxes of Reichsmarks, as well as boxes of silver plate and platinum bars. In addition, Americans found 400 tons of artworks.

When General Eisenhower visited the mine sometime in April to inspect the find, he was taken aback by the wealth of the loot. “Crammed into suitcases and trunks and other containers was a great amount of gold and silver plate and ornament obviously looted from private dwellings throughout Europe,” he wrote. “All the articles had been flattened by hammer blows, obviously to save storage space, and then merely thrown into the receptacle, apparently pending an opportunity to melt them down into gold or silver bars.”

It has been estimated that the value of the gold, silver, and currency recovered from the mines was over $520 million.

American soldiers examine the painting, ‘Wintergarden,’ by Edouard Manet, at Merkers mine.

During the summer of 1945, the currencies found at Merkers and elsewhere by the Americans were returned to various countries, and the process of restituting the artworks found at Merkers and elsewhere in the former German Reich began. A commission called the Tripartite Commission for the Restitution of Monetary Gold (TGC) was established for the distribution of the stolen gold and their return to the rightful owners. The TGC began returning the gold to most countries as quickly as possible. However, cold war factors resulted in some delay. The last gold was not restituted until 1996. Non-monetary gold, such as those taken from victims of Nazi persecution, was handed over to the Preparatory Commission of the International Restitution Organization to be used as evidence in war crime trials at Nuremberg.

Despite the tremendous accomplishments of recovering, moving, and restituting the Merkers treasure, there is still much debate on how much non-monetary gold (e.g., jewelry and dental gold) was melted down and mixed with the monetary gold (i.e., central bank gold) and thus how much restitution should still be made to victims of Nazi persecution and their heirs. It wasn’t until 1997-98 when around fifteen countries agreed to relinquish their claims to their share still held by the Tripartite Gold Commission and donate it to be used as compensation for victims of Nazi persecution. This share amounted to 5.5 metric tons of gold.

Merkers mine today. Photo: A.Savin/Wikimedia Commons

References:

# Greg Bradsher, Nazi Gold: The Merkers Mine Treasure, Prologue Magazine

Comments

Post a Comment