In August 1960, two dogs named Belka and Strelka completed went to space aboard a Soviet spacecraft, stayed for a full day orbiting, and returned to Earth alive and well. They were the first living creatures to survive in outer space. Upon their return, the two dogs became an instant sensation around the world. It also gave the Soviets confidence to send a human into space less than a year later.

Animals have been used in flight long before humans left the planet. In the early years of space flight, all kinds of living beings from rodents to apes were strapped onto rockets and blasted out into space. Once they came back, their psychological effects were observed and physiological changes studied to understand the impact of exposure to space on living tissues. While the Americans experimented with monkeys and chimps, the Soviets preferred to use dogs, because they were easy to train, easily tolerated confined spaces, and formed emotional bonds with humans. Most importantly, they were easy to procure. Most dogs that went to space were strays picked up from the street.

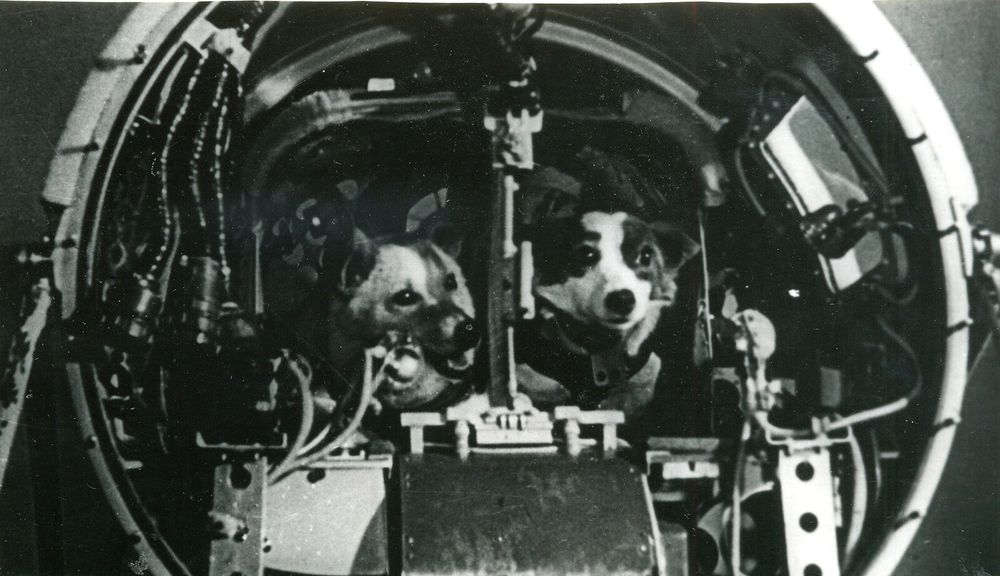

Belka and Strelka after their historic flight.

Lyudmila Radkevich, from the Vostok programme that put Yuri Gagarin in space, remembers how, armed with a ruler, she crisscrossed Moscow suburbs in a car driven by a conscript soldier, looking for stray dogs. These dogs had to be within a certain size (shoulder height - up to 35 cm) and weight (up to 6 kilograms) so that they would fit inside the tiny space capsule. Around 60 dogs aged between 1.5 and three years were picked at the start of the program, but only about a dozen were actually trained for orbital flights. Only female dogs were selected because they required a much simpler design of the waste-disposal system.

The dogs were subjected to detailed medical tests and put through strenuous training programmes, like riding in centrifuges that simulated the high acceleration of a rocket launch and wearing space suits for hours on end. To prepare them for the confines of the space module, the dogs were kept in progressively smaller cages for 15–20 days at a time. Aboard the spacecraft, dogs were fitted with cardiovascular, blood pressure, heartbeat, temperature and motion sensors, some of which had to be surgically placed into the body, but they could be removed if and when the dogs returned.

Also Read: Of Mice, Men And Moon: A Short History of Animals in Space

Scientists decided that the dogs would be sent in pairs, since the animals felt better and calmer when being accompanied. The first attempt on 28 July 1960 ended in a tragedy when a booster exploded just after launch killing the two dogs, Chaika and Lisichka, who were on board. A mere 18 days later, Soviet planners pressed on for another dog flight.

Belka and Strelka undergoing training.

Among the pack was Vilna and Kaplya, who were regarded the most intelligent, quick-witted and hardy. One of the scientists who worked with the dogs decided that they should have more western-sounding names to appeal to a wider audience. He changed their names to Belka and Strelka.

On 19 August 1960, the mongrels Belka and Strelka were blasted into orbit alongside an assortment of earthy beings—a grey rabbit, 42 mice, two rats, flies and several plants and fungi.

“The launch went well, all the medical data coming back from their spacesuits was fine and normal,” Vix Southgate, the author of Dogs in Space: The Amazing True Story of Belka and Strelka, told BBC. “But, by the time they got into orbit, neither of them was moving.”

Then, during the 4th orbit, Belka started vomiting. “It was that which woke them both up,” Southgate said. “From the video recorded on board, you can see the dogs moving around and barking, medical data showed they were calm and not overly stressed.”

After 25 hours and 17 orbits around the earth, ground controllers fired the retro rockets and the dogs descended back to Earth and made a soft landing. When the capsule was opened, Belka and Strelka appeared unharmed by their experience. They were a little sluggish at first and lost their appetite, which was explained by stress. But everything soon returned to normal. The trip turned them into celebrities. Their images were printed on postcards, stamps, and posters. They appeared on television and were feted on TV chat shows.

Belka and Strelka

Strelka and her puppies.

The dogs did not experience any long-term ill-effects from the flight. In fact, Strelka gave birth to six healthy puppies.

Some months later, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev got to visit US president John F. Kennedy, the Soviet premier could not help but brag about Soviet space dogs to the president's wife Jaqueline Kennedy. When Mrs. Kennedy learned that one of the dogs had puppies, she said to Khrushchev "couldn't you send me one?". Two months later, a Soviet ambassador delivered one of the puppies to an astounded Mrs. Kennedy. She was named Pushinka.

Pushkina later gave birth to four puppies that Kennedy jokingly referred to as “pupniks”. Approximately 5,000 people wrote to the White House asking if they could have a puppy. As a result, two of the puppies, Butterfly and Streaker, were given to children in the Midwest, while the other two puppies, White Tips and Blackie, went to friends of the family. When Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, Pushinka was given to a White House gardener and later gave birth to another litter of puppies. Historian Andrew Hager has attempted to track down Pushinka’s descendants but, so far, has drawn a blank. “Certainly, it’s still possible there are descendants of these Russian space dogs out there in the United States,” he says.

President John F. Kennedy, Jacqueline Kennedy, and their children with two of Pushinka's puppies and their other family dogs, at Squaw Island, Hyannis Port, 14 August 1963. Photo: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Belka and Strelka lived fulfilling lives in peace and comfort at the State Research and Testing Institute of Aviation and Space Medicine. Both dogs died of very old age.

Today one can see the stuffed bodies of the two canine heroes, along with lots of accessories from the flight—the cabins in which they flew, scientific equipment, a model of the pressurized landing section of a geophysical rocket—in the Museum of Cosmonautics in Moscow.

The stuffed body of Strelka at the Museum of Cosmonautics in Moscow. Photo: Museum of Cosmonautics

The stuffed body of Belka at the Museum of Cosmonautics in Moscow. Photo: Museum of Cosmonautics

References:

# Belka and Strelka pioneer two-way trip to orbit, Russian Space Web

# Richard Hollingham, The stray dogs that led the space race, BBC

# Alison Gee, Pushinka: A Cold War puppy the Kennedys loved, BBC

# Training, puppies and care. How Belka and Strelka lived before and after the flight, Mos.ru

Comments

Post a Comment