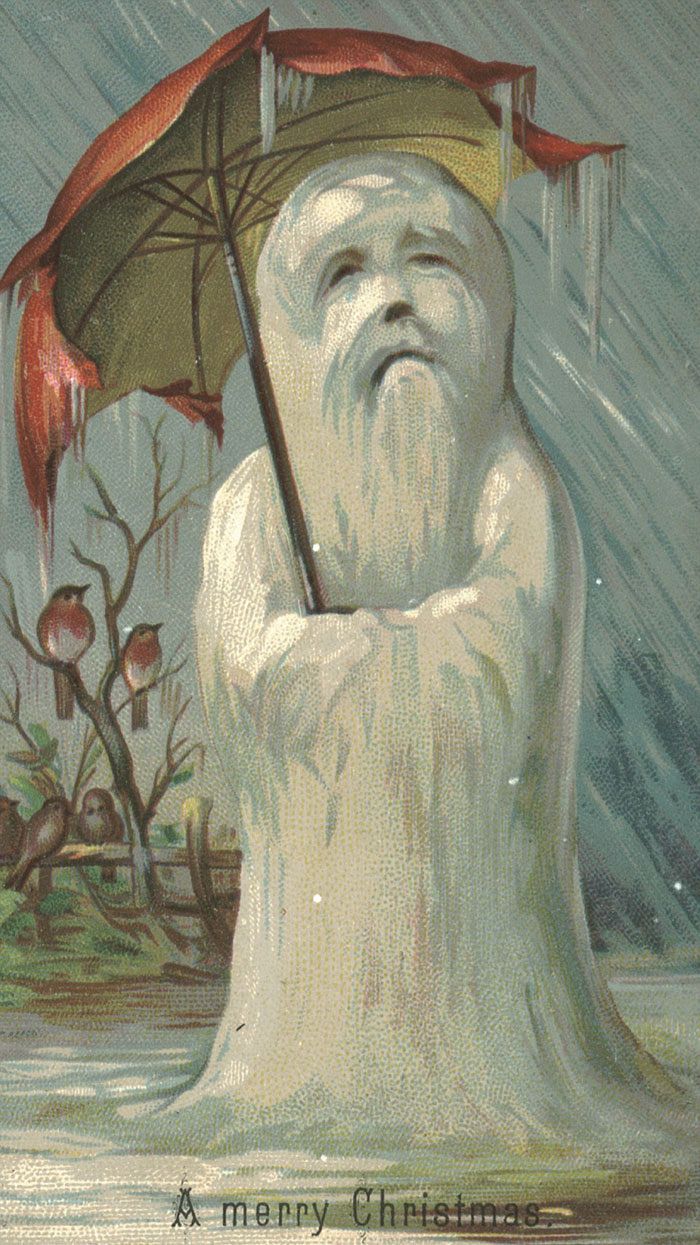

Victorian Christmas cards were a mixed bag of iconography, ranging from religious to everyday things. But one theme common in these seasonal greetings was humor, but not always of the kind we can appreciate today. A dead robin, a frog stabbing another, and Saint Nicholas stuffing a kid in a sack.

The significance of these bizarre imagery is lost, but it is important to remember that the tradition of Christmas was still new, and its iconography had not fully developed.

Christmas celebration in the English-speaking world only dates back to 1848, when Queen Victoria decided to celebrate the holidays with her German-born husband, Prince Albert, by decorating an evergreen tree inside their palace. This unusual celebration was captured in an illustration and published in the Illustrated London News. Soon every British home had a decorated tree decked with small gifts and sweets.

The tradition of exchanging Christmas cards took a few more years. The first card was commissioned by Sir Henry Cole in 1843. It was made by artist J.C. Horsley, and depicted Cole’s family raising a toast surrounded by a decorative trellis and flanked by small scenes depicting acts of giving.

The first ever Christmas card.

Cole had one thousand cards printed and sold them for one shilling each—a pricey thing for ordinary Victorians. The endeavor was failure. However the sentiment caught on. Later in the century, improvements to the chromolithographic printing process made buying and sending Christmas cards affordable for everyone. By the late 19th century, producing and printing Christmas cards had become a lucrative industry.

Of course, not all Victorian Christmas cards were bizarre. In fact, many of the familiar iconography of Christmas and the festive season were set during this period through Christmas cards. This includes winter scenes of robins, holly, evergreens, country churches and snowy landscapes, as well as indoor scenes of seasonal rituals and gift giving, from decorating trees and Christmas dinner, to Santa Claus, and Christmas crackers.

Comments

Post a Comment