The story of the Pied Piper of Hamelin is well known. This dark European folktale with unsettling themes of ingratitude and terrible vengeance has been told and retold for generations. The tale goes something like this:

In the year 1284, there was a serious rat problem in Hamelin, which was at that time a prosperous port on the river Weser in Lower Saxony, Germany. Barges full of corn and wheat arrived every day which was ground in the mills and made into bread and cakes in the bakeries. But the rats came and ate all the corn and the wheat, and the bread and the cakes, and there were fleas everywhere. Life in Hamelin became a nightmare. Desperate for a solution, the town mayor announced a prize of one thousand gold guilders to anyone who could free Hamelin of the rats.

The very next day a mysterious man in bright colorful clothing arrived in town. He claimed to be a rat-catcher, and he promised to get rid of all the mice and rats in Hamelin for the promised sum. The “Pied Piper” then took out a small fife from his pocket and began to play a tune. And as the townsfolk watched in awe, thousands of rats came scurrying out of houses and gutters and warehouses and bakeries and began to follow the Pied Piper. Still playing his fife, the Piper led the mass of mesmerized rats out of town and into the Weser River where they jumped one by one into the water and drowned.

When the Pied Piper returned to the town square to collect his prize, the mayor laughed and gave him only fifty guilders. Enraged, the Piper stomped out of town but not before swearing revenge.

A few days later was Saint John and Paul's day, and while the adults were in church, the piper returned dressed in green and began playing a different tune. This time time it wasn’t rats or mice but the town’s children who came running and dancing towards him. The swarm followed him into the mountain where he disappeared along with the children. Only a lame who couldn’t follow quickly enough, a deaf who couldn’t hear and a blind child remained behind. A total of one hundred thirty children were lost that day.

For a long time, the legend of the Pied Piper was mere folktale kept alive by generation after generation of Hamelin residents until the tale started receiving broader audience through the retelling by the Brothers Grimm. But the tale is much more than fiction. There are evidences that suggest that something deeply traumatic did happen in the German town on 26th of June 1284.

Evidences from the past

We know the precise date from an inscription on a stained-glass window on the town’s church, which stood on the town’s square until it was destroyed in 1660. The window bore the image of a piper and the words: “In the year 1284, on the day of John and Paul, it was the 26th of June, came a colourful Piper to Hamelin and led 130 children away.” The date appears again in Hamelin’s town chronicle. Against the year 1384, the entry simply said, “It is 100 years since our children left.”

The oldest picture of the Pied Piper copied from the glass window of the Market Church in Hamelin.

Accounts of the tale began to appear in subsequent centuries, with the story remaining invariably the same. In a mid-15th century reference found in the Latin chronicle from the German town of Lunenberg, the piper is described as a handsome and well-dressed man about thirty years of age who entered Hamelin and “began to play all through the town a silver pipe of the most magnificent sort.”

The central character of the story, the Piper, was common in medieval times. Pipers were often employed to lead civic celebrations. They wore multicolored dresses, or pied clothes, which was a symbol of low status usually worn by other entertainers such as court fools and executioners. Most pipers lived a vagrant life and were often troublemakers.

The original tale didn’t include rats. The rodent started appearing only in the 16th century, at a time when Europe was gripped by plague, and so the connection between the piper who brought trouble and the vermin who brought illness is not difficult to imagine. At any rate, rats became an important part of the story and it was this version that was popularized by the likes of Robert Browning and Brothers Grimm.

What really happened?

A new theory suggest that the phrase “children of Hamelin” was not meant to convey literal youths, but rather “inhabitants of the town,” and that following the Pied Piper was actually a metaphor for emigrating. In the 13th century, many Germans were persuaded, by offering rewards, to settle in Moravia, East Prussia, Pomerania or in the Teutonic Land by landowners. Consequently, thousands of young adults from Lower Saxony and Westphalia headed east and settled there as evident from dozens of Westphalian place names that show up in this area.

Historian Jürgen Udolph believes that many residents from Hamelin wound up in what is now Poland. In the regions of Prignitz and Uckermark and in the former Pomeranian region, Udolph found families with the same dynastic names as in Hamelin with “amazing frequency”. Udolph surmises that the children were actually unemployed youths who had been sucked into the German drive to colonize its new settlements in Eastern Europe. Landlords often employed certain characters called “lokators” who roamed northern Germany trying to recruit settlers for this purpose. Like a medieval piper, some of them were brightly dressed and all were silver-tongued.

A 14th century portrayal of a “lokator” (with a special hat). In the upper panel he is shown receiving the foundation charter from the landlord. The settlers clear the forest and build houses. In the lower panel, the “lokator” acts as the judge in the village.

An eerily similar tale also exist in the German town of Brandenburg, where a man appeared with a hurdy-gurdy and lured the children away by its beautiful music. In another legend, more than a thousand children left the city of Erfrut singing and dancing in the year 1257 and arrived at Arnstadt, where the citizens there took them in. When parents back home were notified, they brought their children back, but who led them away remained a mystery.

Folktales of rat-catchers are also abound in Germany. In German lore, there is a shape-shifting sprit called Katzenveit who once came to Tripstrille as an exterminator and claimed he cloud drive away the rats. Like the Piped Piper story, he was denied payment and as revenge he led all the cats away from their owners.

Related: Mary And Her Little Lamb

The Pied Piper is a central figure in Hamelin today, although the dark elements to the tale are overlaid with a spirit of fun and merriment. There are Pied Piper-themed restaurants and businesses whose name reflect the legend, and a street named Bungelosenstrasse ("street without drums") purported to be the very street via which the children were led away from the town. No music is played in this street today as a gesture of respect to the town’s lost children.

Every Sunday, throughout summer, in the old town center of Hamelin, actors gather to re-enact the tragic tale that befell the German town centuries ago. In addition, each year the city marks June 26 as "Rat Catcher's Day".

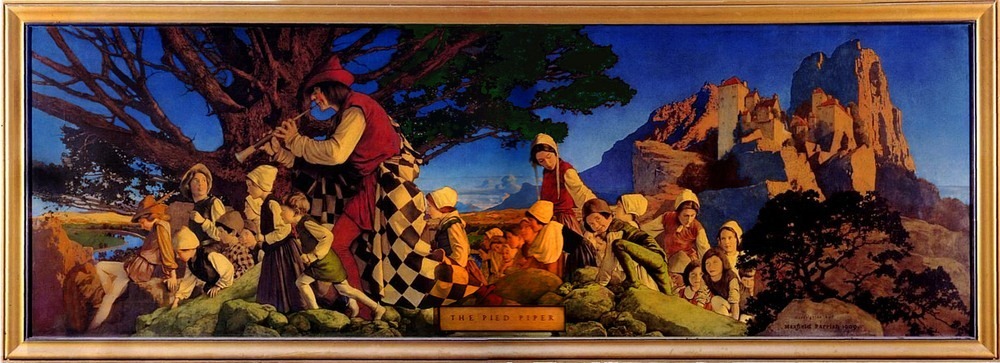

"The Pied Piper of Hamlin", a 16-foot long mural by American painter Maxfield Parrish, at Palace Hotel, San Francisco. Photo credit: Plum leaves/Flickr

A rat tile on the streets of Hamelin. Photo credit: Taylor Sargeant/Flickr

Sculpture of the Pied Piper in Hamelin. Photo credit: hydebrink / Shutterstock.com