For nearly half a century, the Canadian province of Nova Scotia has been sending a gift to the people of Boston in the form of a Christmas tree. This annual tradition of holiday goodwill goes back to 1971, but the events that led to it is older still and was one of great tragedy.

In 1917, the port city of Halifax in Nova Scotia was a bustling scene of activity. The Great War in Europe was in its third year and Halifax’s strategic location in the Caribbean-Canada-United Kingdom shipping triangle made it an integral part of Allied war efforts not only during the First World War but the second one as well. The port’s protective waters sheltered convoys from German U-boat attack, while Halifax’s railway connection and world class port facilities enabled supplies, munitions and troops to be assembled from all around Canada and the US before they headed out into the open Atlantic Ocean and to the Western Front.

The Boston Common Christmas Tree—a gift from Nova Scotia to Boston. Photo credit: Keith J Finks / Shutterstock.com

While the war brought unspeakable horrors in Europe, for many in Halifax it was an era of wealth and opportunity. Millions of tons of supplies passed through the port, arriving by rail and departing on ships towards the war. In addition to vessels of the Royal Canadian Navy and the Royal Navy, hundreds of merchant ships from around the world converged at Halifax, needing repair or resupply. Jobs became plentiful. Migrant workers arrived in search of available work at the dockyards, railyards, the sugar refinery and other factories. Streets were filled with soldiers and sailors and local businesses boomed. The city’s population swelled to more than 60,000.

On the morning of December 6, a Norwegian ship SS Imo left Halifax destined for New York where she would pick up relief supplies for war-torn Belgium. At the same time, a French cargo ship SS Mont-Blanc loaded with explosives was entering the harbor intending to join a convoy which would depart for Europe. In her hold was 2,300 tons picric acid (used for making artillery shells), 200 tons of trinitrotoluene (TNT), 10 tons of gun cotton, and several drums of fuel.

SS Imo was late that morning because she had to wait for her coal to arrive. In order to make up for the lost time, the ship’s captain pushed the throttle down lurching the ship forward at an unsafe speed. As she navigated through the Narrows, the harbor's tightest section, she encountered several incoming ships causing her to be pushed further and further away from her path and into the lane of the incoming SS Mont-Blanc . After a moment of confusion regarding who had the right of way, both ships cutoff their engines but their momentum carried them forward until the ships slammed into each other. The damage to the Mont Blanc was not severe, but the fuel barrels in her hold toppled flooding the deck and the hold below. Minutes later the fumes ignited and the ship was engulfed in an inferno. The crew quickly abandoned the ship and tried to tell anybody who would care to listen about what was going to happen.

Vincent Coleman, a railway dispatcher in the nearby railway yards (photograph on the right), started to flee when he remembered a train from Saint John, New Brunswick, was scheduled to arrive that morning. As the Mont-Blanc burned, Coleman stayed at his post tapping out a message in the final minutes of his life. His message read: “Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbour making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good-bye boys.” The message sent to the stations up the line saved the lives of hundreds.

But only few people understood the seriousness of the situation. In the harbor and on the streets curious onlookers gathered to watch the spectacular plume of black smoke rising towards the sky.

Shortly after nine-o-clock, about twenty minutes after the collision, Mont Blanc ‘s hazardous cargo exploded and the resulting shockwave tore through the city at more than 3,600 km per hour. The blast wave toppled buildings and collapsed roofs and ceiling upon their occupants. The pressure of the shockwave crushed internal organs and exploded lungs and eardrums of those standing close to the explosion. Others were picked up and thrown against buildings and lampposts like rag dolls. Hundreds of people who had been watching the fire from their homes through their windows were blinded when the blast wave shattered the glass panes in front of their eyes.

Map showing the extent of the impact and destruction caused by the Halifax Explosion of Dec. 6, 1917. Graphics by Chris Brackley/Canadian Geographic

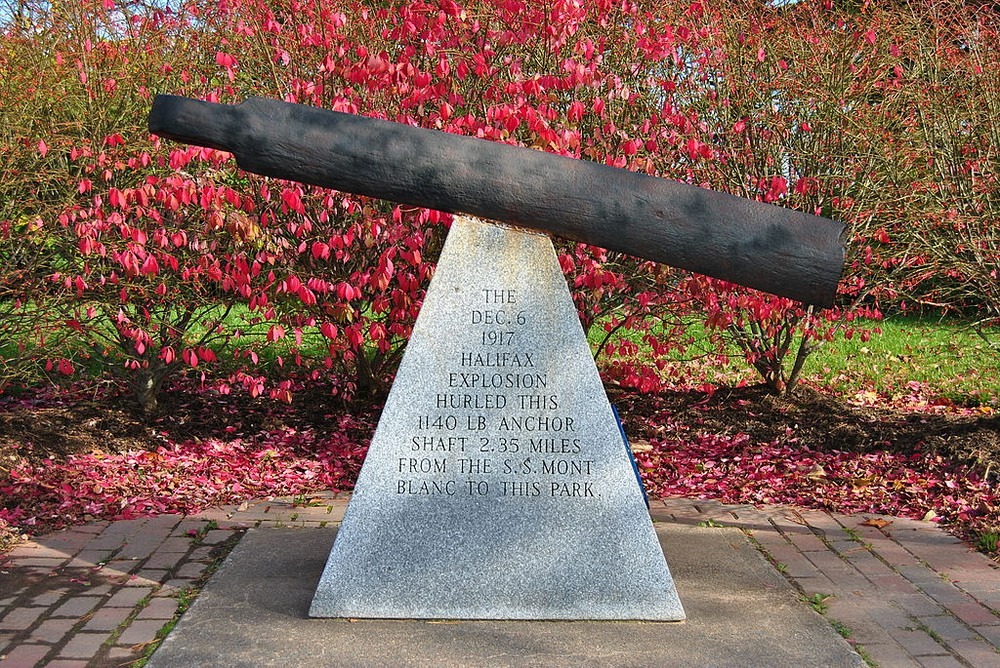

Mont-Blanc's half-ton anchor landed over three kilometers away, where it still remains, and one of her 90 mm gun barrel was sent flying across the city even further some 5.6 kilometers away. Every building within a 2.6-kilometer radius was destroyed or badly damaged. Fires from overturned stoves erupted everywhere.

The explosion displaced all the water around the ship momentarily exposing the harbor floor. Seconds later, water came surging in to fill the void and created a tsunami that rose 60 feet above the high-water mark. The tsunami obliterated a community of Mi'kmaq First Nation who had lived in the area for generations.

The Halifax explosion released an energy equivalent to 2.9 kiloton of TNT. For comparison, the nuclear bomb detonated over Hiroshima was sized at 15 kiloton, only five times stronger. About 1,600 people died instantly from the Halifax explosion and some 9,000 were injured. Roughly 400 more died from their injuries in the days that followed.

A section of Mont Blanc’s anchor that landed on this park is preserved in this monument. Photo credit: Vonkiegr8/Wikimedia

Relief from Boston

One of the first cities to respond to the accident was Boston, located more than a thousand kilometers away. Boston Mayor James Michael Curley sent a message to the U.S. representative in Halifax hours after the explosion. Curley wrote: “The city of Boston has stood first in every movement of similar character since 1822 and will not be found wanting in this instance. I am, awaiting Your Honor’s kind instruction.’’

Curley and Massachusetts Governor Samuel McCall organized a relief effort and asked people to contribute. Within the first hour, they raised $100,000. Thirty of Boston’s leading physicians and surgeons, 70 nurses, a completely equipped 500-bed base hospital unit and a vast amount of hospital supplies were loaded onto a train and left for Halifax within 24 hours of the explosion. When it arrived the morning of December 8, it was the first non-Canadian relief train to arrive at Halifax. In less than a day, a fully-equipped and running impromptu hospital had been set up in a former military officer’s residence. By the time a second train arrived on December 9, Halifax already had enough doctors and clothing for its immediate needs. Massachusetts’s total contribution was at over $750,000.

A view across the devastated neighbourhood of Richmond in Halifax, Nova Scotia after the Halifax Explosion.

The next year on Christmas, Nova Scotia sent a small token of appreciation to Boston—a Christmas tree. This became a tradition from 1971. Most people are honored to donate their trees, and sometime families compete against each other to have their tree chosen. The cutting of the tree is a ceremonial event attended by many dignitaries of the province including the United States Consulate in Halifax and hundreds of locals. The tree then travels by truck across Nova Scotia, crosses the Bay of Fundy by ferry, and then continues the rest of the journey by truck until it reaches Boston. At places along the highway people gather to cheer and get a glimpse of the tree.

The tree usually arrives in Boston in late November or early December, upon which it is erected at the Boston Common Park and decorated with thousands of lights. The event attracts tens of thousands of people.

The gifting of the tree is no small commitment for a small province like Nova Scotia. When the Canadian Broadcasting Corp gathered all the bills for expenses incurred during the 2015 shipment of the tree, they found that it cost the taxpayers $179,000 to cut, transport, and sponsor all the pomp and celebration around the tree’s lighting.

While that might sound huge, the media coverage the province gets in return provides Nova Scotia “a pretty good value” for the money spent, believes Ed McHugh, who teaches business and marketing at Nova Scotia Community College.

Mary Tulle, tourism director for Cape Breton Island, echoes his opinion. Tulle recalled how her grandmother, living three hours from Halifax, watched the dishes shake during the explosion.

“Why do we have to stop saying thank you?” Tulle said.

Smoke cloud from the Halifax Explosion, probably taken off McNabs Island.

The Norwegian steamship Imo aground on Dartmouth shore, after the Halifax Explosion.

Wrecked homes in Halifax.

Soldiers standing guard in the midst of the devastation on Kaye Street east of Gottingen Street, Halifax.

House damaged by the Halifax Explosion.

Building destroyed by the Halifax Explosion.

Ruins of Army & Navy Brewery operated by Halifax Breweries Limited at Turtle Grove, Dartmouth.