Some publicity stunts can be complete train wrecks. Like that one time in 1613 when a real cannon was used to spice up the production of Shakespeare's Henry VIII causing the entire Globe Theatre to burn to ground, or that time when the US Department of Defense decided to fly a Boeing 747 real low over Manhattan for a photo-shoot causing thousands of New Yorkers to nearly die of heart attack. Then, there are train wrecks that are publicity stunts.

From the late 1800s to the early 1900s, staged collisions between trains coming from opposing directions were smashing hits in state fairs across the United States, drawing crowds in tens of thousands. One Joseph S. Connolly, from Iowa, made a career out of it—between 1896 and 1932, “Head-On Joe” successfully staged as many as 73 train wrecks at fairgrounds and other events across the nation, mostly in the Midwest. Connolly’s violent spectacles were so safe that in his nearly four-decade-long career, he never had anyone injured in the collisions. The same cannot be said for William George Crush, the marketing manager of the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railway.

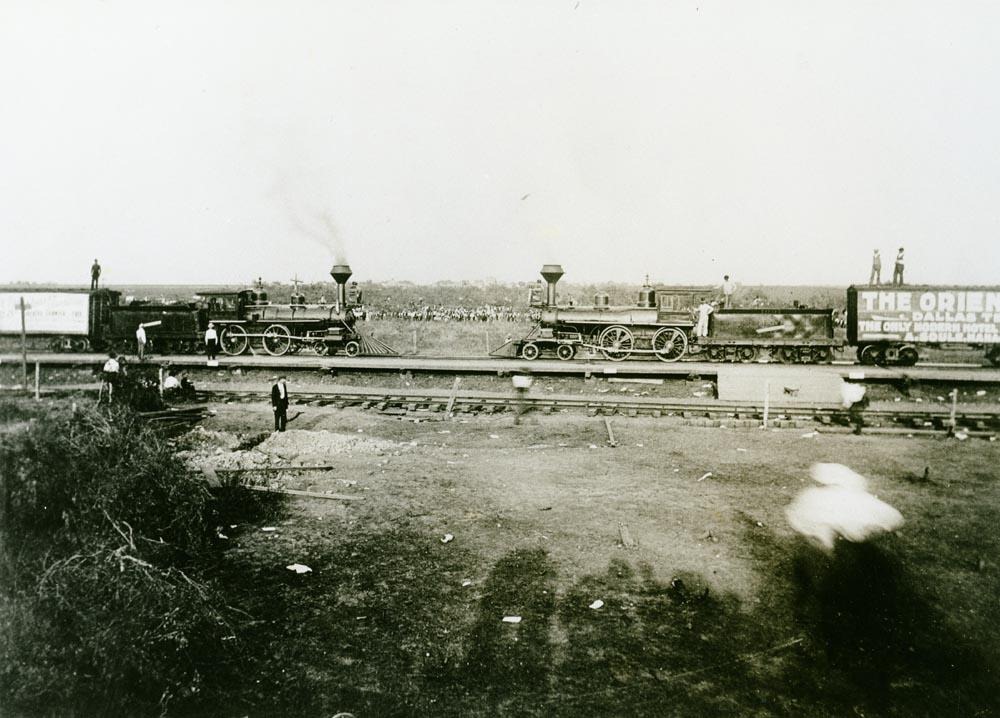

Railway crews pose with the two locomotives in 1896 near Waco, Texas, before the staged crash.

The Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railway, commonly referred to as the "Katy" line, was one of the first railroads to reach Texas in 1872. Once there, it began to spread its iron tentacles acquiring other small railroads in the process while extending its reach to Dallas in 1886, Waco in 1888, Houston in 1893 and to San Antonio in 1901. As the railroad expanded, the Katy replaced its 30-ton steam engines with newer, more powerful 60-ton engines, leading to a stockpile of the older units, for which the railroad now had no use.

In 1896, a Katy agent named William Crush proposed a publicity stunt that could help drum up some business. Only months earlier, the Columbus and Hocking Valley Railroad had staged a locomotive crash in Lancaster, Ohio, and it had been a huge success. Crush believed that if Katy could stage a similar spectacle, the publicity that the event would attract would surely help Katy gain a strong foothold in the region. Crush managed to win the confidence of his superiors, and the project was given a go-ahead.

A location was chosen in McLennan County, Texas, about 15 miles north of Waco near one of Katy's mainlines. In a small valley formed by three hills, four miles of track were laid and a grandstand was set up for spectators. Two wells were drilled to pump water and a large tent, borrowed from the Ringling Brother's circus, was set up to serve food. The place was given the temporary name of “Crush”.

A copy of the tickets sold for the $2 round trip to Crush, Texas

On September 15, 1896, the day of the event, some 40,000 spectators poured in from all around Texas in special excursion trains arranged by Katy, for the price of $2 for a round-trip ticket. To keep people entertained as they waited for the main event, a carnival midway sprang up, with medicine shows, game booths, lemonade stands and cigar stands. Some 300 policemen had to be brought in to keep order. With spectators still arriving by train, the event that was to start at 4 PM, eventually got delayed by an hour.

At 5 PM, the two trains—each comprising of an obsolete 35-ton steam engine pulling six boxcars and plastered with advertisement—were pulled together to have their pictures taken. Crush himself appeared before the crowd riding a white horse and waving his hat like a seasoned performer. When all was ready, the two locomotives slowly backed up to their starting point.

Katy’s engine crews had precisely calculated the exact point of collision, and as the crowd gathered that day, the crew went through their checks a dozen times. To prevent the boxcars from coming apart during the impact, the cars were chained together instead of coupled with a link and pin. Crush was concerned about the boilers exploding during impact, but Katy’s engineers assured him that the boilers were designed to resist ruptures even in a very high-speed crash. Crush still insisted that the crowd be kept back by at least 200 yards, with the exception of the press who were allowed within 100 yards so that photographs could be taken.

The moment of impact

On Crush’s signal, the crews in the locomotives threw the throttles to full and jumped out. As the two engines—one painted green, and the other red—approached, they picked up speed and in less than two minutes met at the designated spot in a violent crash. It was estimated that each train was going at about 45 miles per hour at the moment of impact.

A Dallas Morning News reporter gave a poetic description of the event:

The rumble of the two trains, faint and far off at first, but growing nearer and more distinct with each fleeting second, was like the gathering force of a cyclone. Nearer and nearer they came, the whistles of each blowing repeatedly and the torpedoes which had been placed on the track exploding in almost a continuous round like the rattle of musketry.

But then something unexpected happened. The report continued:

A crash, a sound of timbers rent and torn, and then a shower of splinters... There was just a swift instance of silence, and then as if controlled by a single impulse both boilers exploded simultaneously and the air was filled with flying missiles of iron and steel varying in size from a postage stamp to half of a driving wheel...

Flying metal debris killed two young men and women. An official photographer lost an eye to a steel bolt. Six people were seriously injured while numerous more suffered shrapnel wounds and burns from scalding water erupting from the boilers. Despite the injuries and shock of it, the crowd still rushed forward and swarmed over the wreckage to find souvenirs.

The collision of the two trains

William Crush was fired that very evening, but rehired the next day. Rumor has it that he got a bonus for all the attention he brought the railroad. He worked for the company for 57 years until his retirement.

Curiously, the tragedy didn’t spell the end of fairs crashing locomotives for entertainment. On the contrary, it started it. For the next three decades more than a hundred crashes were orchestrated at state fairs across the United States.

“Train wrecks appealed to the more primitive side of man — the thrill of seeing something destroyed," Reisdorff said in his book on Joseph Connolly, the most proficient train wrecker in history. “Nowadays people go to demolition derbies.”

Thousands of onlookers swarm over the wreckage of the Crush train crash hoping to collect souvenirs.

The original train crash in Lancaster, Ohio, in July 1896 that inspired William Crush. Photo credit: H.F. Pierson/Library of Congress

Video of the 1913 staged train crash in California State Fair.