In the beginning of November 1943, all residents of Imber, a quiet little village at the heart of Salisbury Plain, were summoned to a meeting in the village schoolroom where they were informed that they had just 47 days to pack their bags and leave. The village, they were told, was required by the War Department in order to train American troops in street fighting which they will eventually encounter in Nazi occupied Europe after the hopefully successful invasion of Normandy.

This sudden and forced evacuation upset nearly all inhabitants. Albert Nash, who had been the village’s blacksmith for over forty years, was so heart broken that he died within weeks of receiving the notice. But the government had left the residents with no other alternative but to comply. Besides, during the years before the war, the War Department had systematically purchased all land around Imber, and many properties within the village itself, so that only the village church, vicarage, chapel, schoolroom and the village inn stuck out like sore thumbs in what was essentially government land.

The church in Imber. Photo credit: Ed Webster/Flickr

But there was hope. The villagers were promised they would be able to return to their homes when the war was over. There was also a national sense of patriotism prevalent at the time, so many villagers felt that it was their duty to contribute to the war effort. Convinced that their eviction would be of short duration, several people left their furniture and possessions behind, even leaving canned food in their kitchens. At that time the village had 150 residents.

But the government had other plans. After the war was over, the village continued to be used for military training and as the political and social situation in Northern Ireland worsened it became all the more necessary for government to retain the training ground. Imber was never returned to its people.

“There was no anger at the time. Dismay and disappointment, yes, but the anger took a long time,” said Ken Mitchell, who was 17 at the time his family was forced to leave. “They felt they were helping the country and helping the war effort, and they thought they were coming back.”

In the years that followed, many of Imber's buildings suffered shell and explosion damage, and fell into disrepair.

Following several demonstration by Imber’s former residents, the government agreed to maintain the church and allowed it to be visited for one day each year—on the Saturday closet to St Giles's day.

Abandoned tanks scattered across the Salisbury Plain near Imber. Photo credit: Scott Wylie/Flickr

An abandoned house in Imber. Photo credit: ndl642m/Flickr

Some of the newer structures at Imber military training area. Photo credit: Michael Day/Flickr

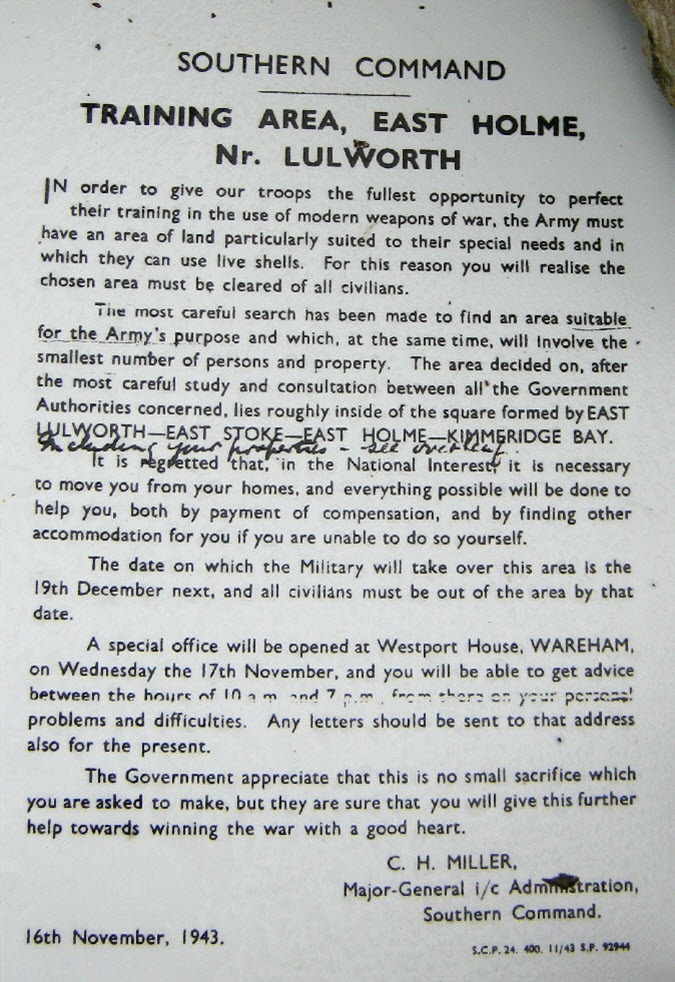

A fate similar to Imber awaited the villagers of Tyneham, in South Dorset. On November 17, 1943, each of Tyneham’s 225 residents received a letter from the War Office stating that they have to leave their homes by December 19, 1943—just over one month away.

The official letter stated: “The Government appreciate that this is no small sacrifice which you are asked to make, but they are sure that you will give this further help towards winning the war with a good heart.”

The eviction notice that Tyneham’s residents received. Photo credit: www.tynehamopc.org.uk

Like Imber, the villagers were promised that Tyneham would be returned to the people once the war was over. As they left, one resident left a hand-written note on the door of the village's church, St. Mary's. It read:

"Please treat the church and houses with care; we have given up our homes where many of us lived for generations to help win the war to keep men free. We shall return one day and thank you for treating the village kindly."

After the war, Tyneham residents demanded the village be returned to them. Protests followed. But in 1948 any hope of returning was dashed when the Army placed a compulsory purchase order on the land and it has remained in use for military training ever since. Many of the village buildings have fallen into disrepair or have been damaged by shelling. The church and the school, however, was preserved, and for a few days every month, usually on weekends, the village is opened to the public.

Photo credit: Dan Meineck/Flickr

Photo credit: Alistair/Flickr

Tyneham St Mary's Church. Photo credit: Liz & Johnny Wesley Barker/Flickr

A abandoned tank near Tyneham. Photo credit: Damien Everett/Flickr

Imber and Tyneham are not the only casualties of the war. In Norfolk, on the east coast, six villages lost their population when the area became the Stanford Battle Area, later renamed to Stanford Training Area. They too were provided false promises of return. Because the majority of the inhabitants were not landowners, they received very little in compensation, and were put into council housing. Many lost their livelihoods.

Simon Knott, who runs a site on Norfolk’s churches, believes that the villages that were left behind were hardly worth returning to. Few houses had running water or electricity. The land was poor farming land, and the residents were already struggling to make a living. The relocated families, on the other hand, found better accommodation and decent jobs on the land and in the factories and shops.

“While you would expect people to feel an emotional attachment to the place they were born, in truth few of the villagers would have wanted to return to the old life,” he wrote.

The six villages now longer exist. Aside from a few scattered ruins and the intact churches, the rest were demolished, while others were adapted for training purposes. Locations of some of the significant buildings of the former villages are now marked with plaques.

Also Read: The Mock Village of Copehill Down

Comments

Post a Comment