One of the most devastating weapons ever invented was not the atomic bomb but napalm, the incendiary agent that was used extensively against German and Japanese cities during the Second World War. Napalm is a thick inflammable gel that sticks to anything that is thrown at and burns at a torturously high temperature destroying buildings made of wood or other combustible materials. Despite being inflammable, napalm is surprisingly stable at high temperatures that allow it to be easily handled and transported. First used during World War 2, napalm and other incendiary gel quickly became the number one weapon in major conflicts around the world including the Korean Wars, the war in Vietnam and the United States’ invasion of Iraq in 2003.

The surviving buildings from the German-Japanese village at Dugway Proving Grounds. Photo: KSL-TV

Napalm was invented by a group of Harvard chemist led by Louis Fieser as a substitute for jellied gasoline mixtures used by the Allied forces. These early forms of incendiary weapons used latex, but after the Japanese captured the rubber plantations in Malaya, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand, natural rubber became scarce prompting many US companies including DuPont and Standard Oil to look for alternatives. In 1942, Louis Fieser and his team became the first to develop such an alternative—a synthetic powdery compound, which when mixed with gasoline turns into an extremely sticky and inflammable substance. They named it napalm, from the words “naphthenic acid” and “palmitic acid”, the two chief constituents of the agent.

Napalm was first tested on a football field near the Harvard Business School. Later tests were carried out at Jefferson Proving Ground on derelict farm buildings. But more extensive testing was needed in order to determine the effectiveness of the weapon against German and Japanese cities.

Aerial view of the German-Japanese village at Dugway Proving Grounds. Photo: US Army

In the spring of 1943, the US Army began erecting detailed reproductions of typical German and Japanese houses at Dugway Proving Ground in the Great Salt Lake Desert, Utah.

The German buildings were designed by Jewish architects Eric Mendelson and Konrad Wachsmann. Mendelsohn had designed many well known buildings in Berlin, but was excluded from the Prussian Art Academy in 1933, following which he emigrated first to London, and then to the United States in 1941. Wachsmann fled to France and reached the US shortly before the occupation with the help of Albert Einstein, where he joined Walter Gropius to work on the development of prefabrication systems.

On the German side of the village, two different types of buildings were constructed—one duplicating Rhineland construction with slate on sheathing roofs, and the other with tile on batten roofs, which was more typical of central and northern Germany.

Two German houses at the German-Japanese village at Dugway Proving Grounds. Photo: Library of Congress

In order to make the construction as authentic as possible, wood was imported from Murmansk, Russia, because it was the closest they could get to the wood favored by German builders. To simulate Germany's humid climate, steam radiators sprayed the wood throughout the night. The rooms were also outfitted with the appropriate furniture typical of an average working class family. A large room was furnished as a combination of a living and eating room, the two smaller ones as kitchen and sleeping room. The amount and distribution of the furniture was made as similar as possible to real German households. Much of this work was done by a set of designers from RKO studios in Hollywood. Faithfully recreating the interior was needed in order to analyze how furniture contributed to the burning process of the houses.

For the Japanese side of the village, the Army hired Czechoslovakian architect Antonin Raymond, who worked several years in Japan. The Russian-born Boris Laiming also added valuable knowledge from his hobby of studying fires in Japan, especially the devastating fire that followed the 1923 Kantō earthquake.

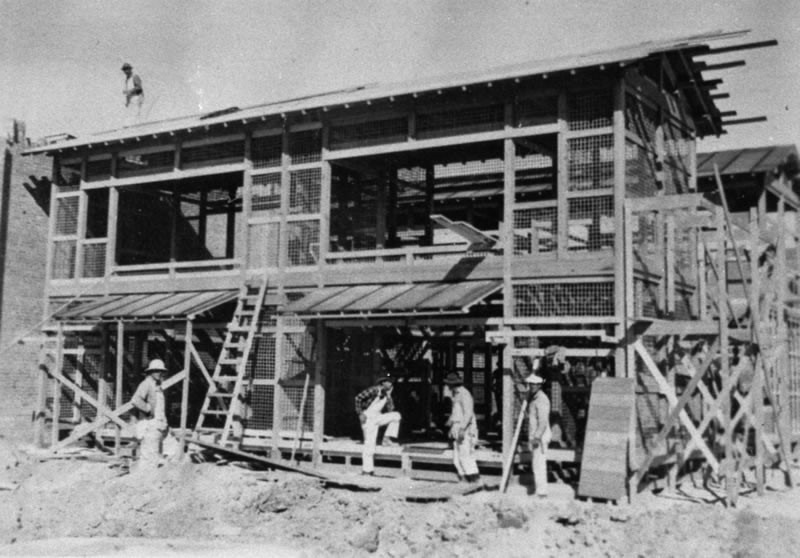

Workers build a Japanese house at Dugway Proving Grounds. Photo: JapanAirRaids.org

Reproducing the Japanese structures proved to be more difficult. Many materials such as Sugi (Japanese cedar), the main construction timber, and Tatami mats for flooring were not readily obtainable outside of Japan, and so the US Army had to use substitutes. The Army managed to confiscate a shipment of Russian Spruce en-route from Siberia, which was used to simulate Sugi. Mountain Douglas Fir trees were used to simulate another Japanese wood known as Hinoki. Rattan was used as a substitute for bamboo which was typical in Japanese construction. For Tatami mats, replicas made out of agave fibers were used.

Once the incendiary tests began, officers recorded the results from 400 yards away in a reinforced concrete bunker that still stands today. They documented everything from how intensely the fire burned, how long it took, and so on. Once the Army got the information they needed, the flames were doused and specials crews repaired the structures so that they could be bombed again. The volume of data generated by these tests proved invaluable in orchestrating the controversial firebombing raids over Dresden and Tokyo.

Photo: JapanAirRaids.org

Photo: JapanAirRaids.org

Photo: JapanAirRaids.org

What made this entire exercise disturbing was that the engineering was explicitly directed towards the destruction of civilian life. The army built mock houses and not factories, making very clear what these weapons were meant to accomplish.

Tokyo was firebombed on the night of 9 and 10 March 1945, in what historians describe as the single most destructive bombing raid in human history. Hundreds of American B29s dropped two thousand tons of incendiary bombs on the capital city, destroying over a quarter of the city and leaving an estimated 100,000 civilians dead. The bombs were mostly 500-pound cluster devices that broke up into 38 individual “M69s” after they were released from the air. These M69s punched through the thin roof and after a delay of 3 to 5 seconds, threw a jet of flaming napalm globs that consumed in flames everything it touched. As many as 67 Japanese cities were subjected to incendiary attacks during the course of the war. Some 40,000 tons of M69s were used in these attacks.

Today, very little of the original German-Japanese village remain on site. There is a double unit on the German side of the village still standing, as well as the concrete observation bunker.

Tokyo burns under firebomb assault, 26 May 1945. Photo: US Army Air Forces

The German-Japanese village today. Photo: KSL-TV

Observation bunker. Photo: KSL-TV

References:

# Dugway Proving Ground, Utah, TheMilitaryStandard

# Burning down the house: The German-Japanese village, Cabinet Magazine

# Sloan Schrage, Dugway's German Village shows how far Allies were willing to go to end WWII, KSL

# Alex Wellerstein, Who Made That Firebomb?, The Nuclear Secrecy Blog

Comments

Post a Comment