About four miles east of Coudersport, in the town of Sweden, in Potter County, Pennsylvania, lies the most puzzling geological anomaly. It’s a small cave, or a pit, with an eight-feet-wide by ten-feet-long opening in the ground. At the bottom of the forty-foot deep chasm is a layer of ice. Large icicles measuring up to 25 feet long and often up to 3 feet thick hangs from the sides and just below the cave’s mouth.

This is the Coudersport Ice Mine, one of nature’s many ice-manufacturing plants. However, unlike regular ice caves that form only in winter, the ice in Coudersport Ice Mine forms during the warmest season of the year. The ice starts to form in spring, increasing in volume as the weather gets hotter and hotter. When winter arrives and there is snow and ice everywhere, and when it would seem to be the most natural time for ice formation, the ice in Coudersport Ice Mine melts away to nothing.

Photo credit: rivercouple75/Tripadvisor

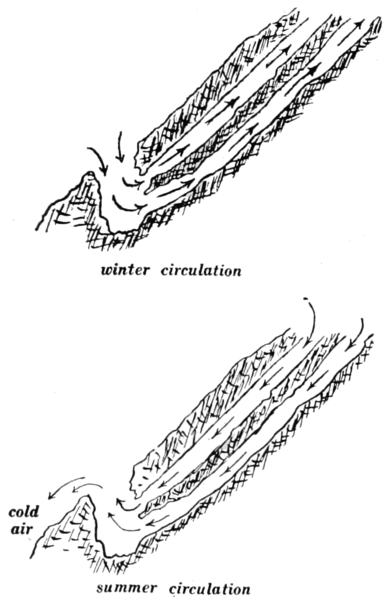

What causes this bizarre behavior is largely a mystery, but the current prevailing theory states that during winter, cold air slips into the heart of the mountain through cracks in the rock formation, and due to the unusual interconnection of the crevices here, that cold air gets concentrated into chambers such as this one. When this cold air comes in contact with percolating groundwater, ice is formed. This happens only during spring and summer because of the availability of groundwater during these seasons.

As winter approaches, the mountain once again starts taking cold air and slowly pushes out the warm air that had become trapped in the rocks from the preceding summer. As the warm escapes through the ice cave, it melts the ice from the summer.

The Coudersport Ice Mine was discovered in 1894 by a silver prospector named John Dodd, and the mysterious annual phenomenon had perplexed him. According to an article published in March 1913, in Popular Science Monthly, Dodd had conducted a few experiments of his own:

He says that two sticks of dynamite were placed about eight feet back into a crevice at the bottom of the shaft and fired without turning a stone or dislodging any earth in the shaft. A possible conclusion is that there is a cave underneath the mine large enough to absorb the shock of the explosion.

Later, Dodd made an opening in the hillside ten feet deep by twenty across, and found crevices in the rock from which he collected ice weighing twenty and twenty-five pounds. These crevices are the ones that possibly trap and bring cold air into the ice cave. Dodd’s litter experiment also shows that ice forms not only inside the cave but inside the crevices as well.

The mine was relatively unknown at the time the article was published. Today, it’s a curious little attraction. While you can’t go into the cave itself, you can do gather around a wooden platform and lean over the metal railing that surrounds a small opening directly over the ice mine and enjoy the whiffs of cool breeze that comes from below.

Photo credit: www.pri.org

Sources: Wikipedia / www.pri.org / Mother Nature Network / Popular Science Monthly

Nice Icehole you've got there

ReplyDelete