During the 16th and 17th century, particularly around the time of the Safavid reign, the Iranian folks built a large number of towers to house pigeons. The pigeons were domesticated not for their meat (pigeon is especially revered in Islam), but rather for their droppings, which the locals collected and used to fertilize melon and cucumber fields. The Safavids had a particular liking for melons and consumed them in staggering numbers. Pigeon dung was thought to be the best manure for these crops, and the towers were built for the purpose of attracting pigeons to them so that they would nest in the towers and their dung could be harvested. Built with brick and overlaid with plaster and lime, these towers were some of the finest dovecots in any part of the world. At its peak, Isfahan had an estimated 3,000 pigeon towers. Today, around 300 remain scattered throughout the countryside in various states of disrepair. Modern fertilizers and chemicals have rendered these magnificent structures obsolete leading to their abandonment in the fields, where they continue to deteriorate due to lack of maintenance.

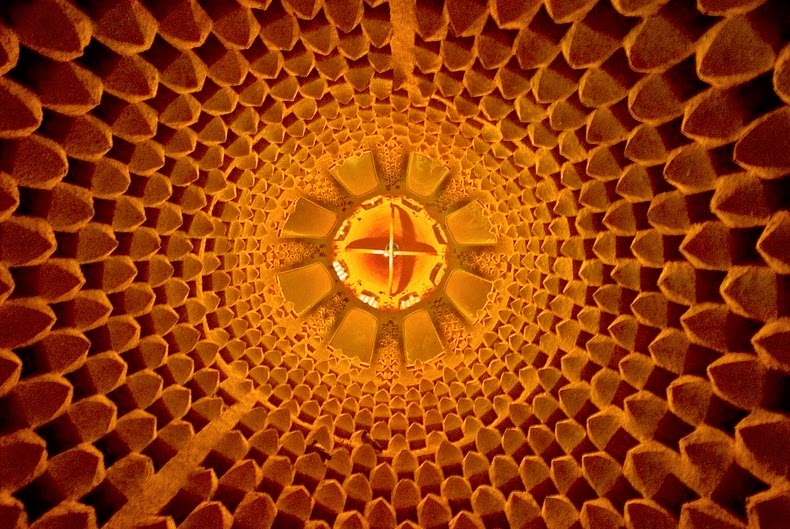

The inside of a pigeon tower, looking from the bottom towards the ceiling. The walls are lined with hundreds of pigeonholes. Photo credit

The typical pigeon tower is cylindrical and constructed of unfired mud brick, lime plaster and gypsum. The towers range from 10 to 22 meters in diameter and stand 18 or more meters high, and could house up to 14,000 pigeons. Because many animals prey on pigeons, the towers were constructed as impenetrable fortresses that could shelter the pigeons from predators. The small size of the entrances prohibits large birds such as hawks, owls or crows from entering inside.

The interior consists of endless nesting balconies in checkerboard pattern scattered uniformly along the walls. The pigeonholes measured approximately 20 by 20 by 28 centimeters (8 x 8 x 11"), with a short projecting perch made of dried clay set at the opening of each one. The walls were slanted inwards allowing pigeon dung to fall directly into a central collection pit at the foot of the tower, where it dried. The towers were opened once a year to harvest the dung that, in the 17th century, sold for four British pence per 5.5-kilogram.

Photo credit: Arthur Thevenart / Corbis

The checkerboard arrangement of pigeonholes made efficient use of space, maximizing the number of holes and keeping the weight and the amount of building material used in the tower to a minimum. The interior walls were further strengthened with interior arches, barrel-vaulted ceilings, circular staircases and both interior and exterior buttresses. Wood was rarely used in the construction of the towers and, despite the long tradition of building them, no two are exactly alike.

The birds were not captured and trained to occupy the towers, rather, they were instinctively attracted to them because they resembled the rocky ledges and crevices in which pigeons like to nest, mate and rear their young in the wild. The birds were provided housing, but not food. The flocks of pigeons went out to seek water and to forage during the day. At night the birds would return to the pigeon towers.

Dung from the pigeons were mainly used as fertilizers, but they also found use in the leather industry where it was used to soften the leather, a process known as “bating”. More importantly, the dung was an essential ingredient in the manufacture of gunpowder.

Pigeon dung, and hence pigeon towers, were rendered functionally obsolete by the modern use of chemical fertilizers and tanning chemicals. Out of the 300 or so towers that remain today around Isfahan, 65 of them are nominally protected by their inclusion on the National Heritage List. Some of them still attract small flocks of wild pigeons who roost in the towers despite collapsed ceilings, cracked walls and their general state of tumbledown.

Sources: Saudi Aramco World / Historical Iran / Isfahan.org.uk / Canadian Center of Science and Education

Comments

Post a Comment